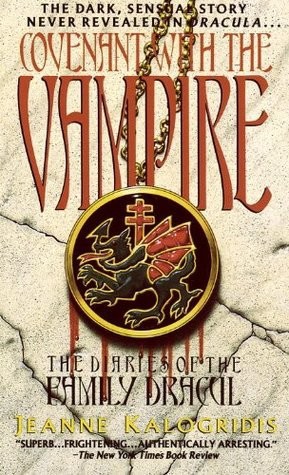

Covenant With the Vampire

COVENANT WITH THE VAMPIRE

COVENANT WITH THE VAMPIRETHE DIARIES OF THE FAMILY DRACUL

JEANNE KALOGRIDIS

A DELL BOOK

Published by Dell Publishing a division of Random House, Inc. 1540 Broadway

New York, New York 10036

If you purchased this book without a cover you should be aware that this book

is stolen property. It was reported as unsold and destroyed to the publisher

and neither the author nor the publisher has received any payment for this stripped

book.

Source for some of the information on the Dracul Family Tree is

Dracula:

Prince of Many Faces

by Radu R. Florescu and Raymond T. McNally (Little,

Brown, 1989).

Copyright © 1994 by Jeanne Kalogridis

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted

in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying,

recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system, without the written

permission of the Publisher, except where permitted by law. For information

address: Delacorte Press, New York, New York.

The trademark Dell is registered in the U.S. Patent and Trademark Office.

ISBN 0-440-21543-9

Reprinted by arrangement with Delacorte Press

Printed in the United States of America

Published simultaneously in Canada

October 1995

10 9 8 7 6 5

For S.

I am enormously indebted to:

My editor and evil twin, Jeanne Cavelos, for her saintly patience, her constant

encouragement, and her unshakable faith that this overdue manuscript would someday

materialize on her desk;

My agent, Russell Galen, for his exemplary professionalism and his suggestion

that I try my hand at historical fantasy;

My cousin, Laeta Kalogridis, whose painstaking edit of the manuscript powerfully

shaped this book for the better;

My dear friend, Kathleen OMalley, whose comments had a profound influence

on how the tale was told; Toby and Ilona Scott, who freely offered their expertise

on all things Roumanian;

Most of all, the two men whose constant love makes all effort worthwhile: my

father, Irwin, and my beloved husband, George.

The devil is an angel, too.

Miguel de Unamuno

The Diary of Arkady Tsepesh

[undated, on the inside cover in jagged scrawl]

God, in Whom I put no faith, help me! I do not believe in You -

did

not, but if I am to accept such infinite Evil as I have become, then I pray

infinite Good exists as well, and that it has mercy on what remains of my soul.

I

am the wolf.

I

am Dracul. The blood of innocents stains

my hands, and now I wait to kill

him

The Diary of Arkady Tsepesh

5 April, 1845.

Father is dead.

Mary has been asleep for hours now, in the old trundle bed my brother Stefan

and I shared as children. Poor thing; she is so exhausted that the glow from

the taper does not disturb her. How incongruous to see her lying there beside

Stefan's small ghost, surrounded by the artifacts of my childhood inside these

crumbling, high-ceilinged stone walls, their corridors a whisper with the shades

of my ancestors. It is as if my present and past had suddenly collided.

Meanwhile, I sit at the old oaken desk where I learned my letters, occasionally

running my hand over the pitted surface scarred by successive generations of

fidgety Tsepesh young. Dawn nears. Through the north window, I can see against

the lightening grey sky the majestic battlements of the family castle where

Uncle still dwells. I ponder my proud heritage, and I weep - softly, so as not

to wake Mary, but tears bring no release of sorrow; writing alone eases the

grief. I shall begin a journal, to record these painful days and to aid me,

in future years, to better remember Father. I must keep his memory ever green

in my heart, so that one day I can paint for my yet-unborn child a verbal portrait

of his grandfather.

I had so hoped he would live long enough to see - No. No more tears. Write!

You will grieve Mary if she wakes to see you carrying on like this. She has

suffered enough on your behalf.

The past several days have seen us in ceaseless motion, borne across Europe

in boats, carriages, trains. I felt I was not so much retracing my journey across

a continent as traveling back in time, as though I had left my present behind

in England and now moved swiftly and irrevocably back into a dark ancestral

past. In the rocking wagon-lit from Vienna, as I lay beside my wife and stared

at the play of light and shadow against drawn blinds, I was riven by the sudden

fearful conviction that the happy life we led in London could never be reclaimed.

There was nothing to tie me to that present, nothing but the child and Mary.

Mary, my anchor, who slept soundly, untroubled and unshakable in her loyalty,

her contentment, her beliefs. She lay on her side, the only position now comfortable

in this seventh month of her confinement, her gold-fringed alabaster lids veiling

the blue ocean of her eyes. I gazed through the thin white linen of her nightgown

at her taut belly, at the unguessable future there, and touched a hand to it,

gently, so as not to waken her - moved to sudden tears of gratitude. She is so

sturdy, so calm; as placid as a motionless sea. I try to hide my wellings of

emotion for fear their intensity will overwhelm her. I always told myself I

had left that aspect of my self in Transylvania - that part given to dark moods

and despair, that part which had never known real happiness until I deserted

my native land. I wrote volumes of black, brooding poetry in my native language,

before going to England; once there, I gave up writing poems altogether. I have

never attempted any literature other than prose in my acquired tongue.

That was a different life, after all; ah, but my past has now become my future.

On the rumbling train bound from Vienna, I lay beside my wife and unborn child

and wept - out of joy that they were with me, out of fear that the future might

see that joy dimmed. Out of uncertainty at the news that awaited me at the manor

high in the Carpathians.

At home.

But in all honesty, I cannot say that news of Father's death was a shock. I

had a strong premonition of it on the way from Bistritsa (Bistritz, I mean to

say. I shall keep this journal entirely in English, lest I forget it too quickly).

A strange feeling of dread overcame me the instant I set foot inside the coach.

My mind was already uneasy - we had received Zsuzsanna's telegram over a week

before, with no way of knowing whether his condition had worsened or improved - and

it was not soothed by the reaction of the coachman when I told him our destination.

A hunchbacked elderly man, he peered into my face and exclaimed, as he crossed

himself:

"By Heaven! You are of the Dracul!"

The sound of that hated name made me flush with anger. "The name is Tsepesh,"

I corrected him coldly, though I knew it would do no good.

"Whatever you say, good sir; only remember me kindly to the prince!" And the

old man crossed himself again, this time with trembling hand. When I told him

in fact my great-uncle, the prince, had arranged for a driver to meet us, he

grew tearful and begged us to wait until morning.

I had forgotten about the superstition and prejudice rampant among my uneducated

native countrymen; indeed, I had forgotten what it was like to be feared and

secretly despised for being

boier,

a member of the aristocracy. I had

often faulted Father for the intense disdain he showed toward the peasants in

his letters; now I was ashamed to find that same attitude aroused in myself.

"Do not be ridiculous," I curtly told the driver, aware that Mary, who did

not speak the language, nonetheless had heard the fear in the old peasant's

tone and was watching us both with anxious curiosity. "No harm will come to

you."

"Or to my family. Only swear it, good sir

!"

"Or to your family. I swear it," I said shortly, and turned to help Mary into

the coach. While the old man backed towards the driver's seat, bowing and proclaiming,

"God bless you, sir! And the lady, too," I tried to allay my wife's curiosity

and concern by saying that local superstition forbade night travel into the

forest. It was at least the partial truth.

And so we headed into the Carpathians. It was late afternoon, and we were already

exhausted from a full day's travel, but the urgency of Zsuzsanna's telegram

and Mary's determination that we should meet the prearranged carriage propelled

us onward.

As we rumbled past a foreground of verdant forested slopes dotted with farmhouses

and the occasional rustic village, Mary remarked with sincere pleasure on the

countryside's charm - cheering me, for I feel no small amount of guilt at bringing

her to a country where she is a stranger. I confess I had forgotten the beauty

of my native land after years of living in a crowded, dirty city. The air is

clean and sweet, free from urban stench. It is early spring, and the grass has

already greened, and the fruit trees are just beginning to bloom. Some few hours

into our journey the sun began to set, casting a pale rosy glow on the looming

backdrop of spiraling, snow-covered Carpathian peaks, and even I drew in a breath

at their awesome splendor. I must admit that, mingled with the growing sense

of dread, I felt a fierce pride, and a longing for home I had forgotten I possessed.

Home. A week ago, that word would have denoted London

As dusk encroached, a lugubrious gloom permeated the landscape and my thoughts.

I fell to ruminating on the fearful gleam in our driver's eye, on the hostility

and superstition implied by his actions and words.

The change in the countryside mirrored my state of mind. The farther into the

mountains we ventured, the more stunted and gnarled the roadside growth became,

until ascending a steep slope I spied nearby an orchard of deformed, dead plum

trees, rising black against the evanescent purple twilight. The trunks were

stooped by wind and weather like the ancient peasant women carrying on their

backs a too-heavy burden; the twisted limbs thrust up towards heaven in a mute

plea for pity. The land seemed to grow increasingly misshapen; as misshapen

as its people, I thought, who were more crippled by superstition than any infirmity

of body.

Can we be truly happy among them?

Shortly thereafter, night fell, and the orchards gave way to straight, tall

forests of pine. The passing blur of dark trees against darker mountains and

the rocking of the carriage lulled me into an uneasy sleep.

I fell at once into a dream:

Through a child's eyes, I gazed up at towering evergreens in the forest overshadowed

by Great-uncle's castle. Treetops impaled rising mists, and the cool, damp air

beneath smelled of recent rain and pine. A warm breeze lifted my hair, stirred

leaves and grass that gleamed, be-jeweled with sunlit drops of moisture.