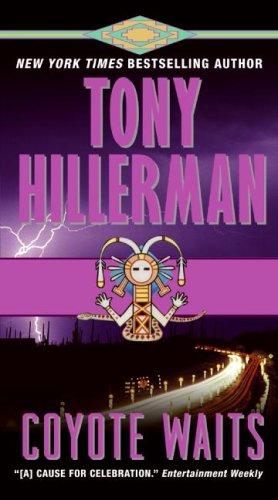

Coyote Waits

Authors: Tony Hillerman

Tags: #Police Procedural, #Chee; Jim (Fictitious character), #Police, #Mystery & Detective, #General, #Southwestern States, #Fiction, #Leaphorn; Joe; Lt. (Fictitious character)

Synopsis:

When a bullet kills Officer Jim Chee’s friend Del, a Navajo shaman is arrested for homicide, but the case is far from closed — and requires Joe Leaphorn’s involvement, as well. The car fire didn’t kill Officer Jim Chee’s good friend, Navajo Tribal Policeman Delbert Nez — a bullet did. A whiskey-soaked Navajo shaman is found with the murder weapon. The old man is Ashie Pinto. He’s quickly arrested for homicide and defended by a woman Chee could either love or loathe. But when Pinto won’t utter a word of confession or denial, Lt. Joe Leaphorn begins an investigation. Soon, Leaphorn and Chee unravel a complex plot of death involving an historical find, a lost fortune ... and the mythical Coyote, who is always waiting, and always hungry.

TONY HILLERMAN

Copyright © 1990 by Tony Hillerman.

Charles Unzner,

and

For our world-class next-door neighbors —

Jim and Mary Reese,

and Gene and Geraldine Bustamante

OFFICER JIM CHEE was thinking that either his right front tire was a little low or there was something wrong with the shock on that side. On the other hand, maybe the road grader operator hadn’t been watching the adjustment on his blade and he’d tilted the road. Whatever the cause, Chee’s patrol car was pulling just a little to the right. He made the required correction, frowning. He was dog-tired.

The radio speaker made an uncertain noise, then produced the voice of Officer Delbert Nez. “. . . running on fumes. I’m going to have to buy some of that high-cost Red Rock gasoline or walk home.”

“If you do, I advise paying for it out of your pocket,” Chee said. “Better than explaining to the captain why you forgot to fill it up.”

“I think . . .” Nez said and then the voice faded out.

“Your signal’s breaking up,” Chee said. “I don’t read you.” Nez was using Unit 44, a notorious gas hog. Something wrong with the fuel pump, maybe. It was always in the shop and nobody ever quite fixed it.

Silence. Static. Silence. The steering seemed to be better now. Probably not a low tire. Probably . . . And then the radio intruded again.

“. . . catch the son-of-a-bitch with the smoking paint gun in his hand,” Nez was saying. “I’ll bet then . . .” The Nez voice vanished, replaced by silence.

“I’m not reading you,” Chee said into his mike. “You’re breaking up.”

Which wasn’t unusual. There were a dozen places on the twenty-five thousand square miles the Navajos called the Big Rez where radio transmission was blocked for a variety of reasons. Here between the monolithic volcanic towers of Ship Rock, the Carrizo Range, and the Chuska Mountains was just one of them. Chee presumed these radio blind spots were caused by the mountains but there were other theories. Deputy Sheriff Cowboy Dashee insisted that it had something to do with magnetism in the old volcanic necks that stuck up here and there, like great black cathedrals. Old Thomasina Bigthumb had told him once that she thought witches caused the problem. True, this part of the Reservation was notorious for witches, but it was also true that Old Lady Bigthumb blamed witches for just about everything.

Then Chee heard Delbert Nez again. The voice was very faint at first. “. . . his car,” Delbert was saying. (Or was it “. . . his truck”? Or “. . . his pickup”? Exactly, precisely, what had Delbert Nez said?) Suddenly the transmission became clearer, the sound of Delbert’s delighted laughter. “I’m gonna get him this time,” Delbert Nez said.

Chee picked up the mike. “Who are you getting?” he said. “Do you need assistance?”

“My phantom painter,” Nez seemed to say. At least it sounded like that. The reception was going sour again, fading, breaking up into static.

“Can’t read you,” Chee said. “You need assistance?”

Through the fade-out, through the static, Nez seemed to say “No.” Again, laughter.

“I’ll see you at Red Rock then,” Chee said. “It’s your turn to buy.”

There was no response to that at all, except static, and none was needed. Nez worked up U.S. 666 out of the Navajo Tribal Police headquarters at Window Rock, covering from Yah-Ta-Hey northward. Chee patrolled down 666 from the Ship Rock subagency police station, and when they met they had coffee and talked. Having it this evening at the service station-post office-grocery store at Red Rock had been decided earlier, and it was upon Red Rock that they were converging. Chee was driving down the dirt road that wandered back and forth across the Arizona-New Mexico border southward from Biklabito. Nez was driving westward from 666 on the asphalt of Navajo Route 33. Nez, having pavement, would have been maybe fifteen minutes early. But now he seemed to have an arrest to make. That would even things up.

There was lightning in the cloud over the Chuskas now, and Chee’s patrol car had stopped pulling to the right and was pulling to the left. Probably not a tire, he thought. Probably the road grader operator had noticed his maladjusted blade and overcorrected. At least it wasn’t the usual washboard effect that pounded your kidneys.

It was twilight — twilight induced early by the impending thunderstorm — when Chee pulled his patrol car off the dirt and onto the pavement of Route 33. No sign of Nez. In fact, no sign of any headlights, just the remains of what had been a blazing red sunset. Chee pulled past the gasoline pumps at the Red Rock station and parked behind the trading post. No Unit 44 police car where Nez usually parked it. He inspected his front tires, which seemed fine. Then he looked around. Three pickups and a blue Chevy sedan. The sedan belonged to the new evening clerk at the trading post. Good-looking girl, but he couldn’t come up with her name. Where was Nez? Maybe he actually had caught his paint-spraying vandal. Maybe the fuel pump on old 44 had died.

No Nez inside either. Chee nodded to the girl reading behind the cash register. She rewarded him with a shy smile. What was her name? Sheila? Suzy? Something like that. She was a Towering House Dineh, and therefore in no way linked to Chee’s own Slow Talking Clan. Chee remembered that. It was the automatic checkoff any single young Navajo conducts — male or female — making sure the one who attracted you wasn’t a sister, or cousin, or niece in the tribe’s complex clan system, and thereby rendered taboo by incest rules.

The glass coffee-maker pot was two-thirds full, usually a good sign, and it smelled fresh. He picked up a fifty-cent-size Styrofoam cup, poured it full, and sipped. Good, he thought. He picked out a package containing two chocolate-frosted Twinkies. They’d go well with the coffee.

Back at the cash register, he handed the Towering House girl a five-dollar bill.

“Has Delbert Nez been in? You remember him? Sort of stocky, little mustache. Really ugly policeman.”

“I thought he was cute,” the Towering House girl said, smiling at Chee.

“Maybe you just like policemen?” Chee said. What the devil was her name?

“Not all of them,” she said. “It depends.”

“On whether they’ve arrested your boyfriend,” Chee said. She wasn’t married. He remembered Delbert had told him that. (“Why don’t you find out these things for yourself,” Delbert had said. “Before I got married, I would have known essential information like that. Wouldn’t have had to ask. My wife finds out I’m making clan checks on the chicks, I’m in deep trouble.”)

“I don’t have a boyfriend,” the Towering House girl said. “Not right now. And, no. Delbert hasn’t been in this evening.” She handed Chee his change, and giggled. “Has Delbert ever caught his rock painter?”

Chee was thinking maybe he was a little past dealing with girls who giggled. But she had large brown eyes, and long lashes, and perfect skin. Certainly, she knew how to flirt. “Maybe he’s catching him right now,” he said. “He said something on the radio about it.” He noticed she had miscounted his change by a dime, which sort of went with the giggling. “Too much money,” Chee said, handing her the dime. “You have any idea who’d be doing that painting?” And then he remembered her name. It was Shirley. Shirley Thompson.

Shirley shuddered, very prettily. “Somebody crazy,” she said.

That was Chee’s theory too. But he said: “Why crazy?”

“Well, just because,” Shirley said, looking serious for the first time. “You know. Who else would do all that work painting that mountain white?”

It wasn’t really a mountain. Technically it was probably a volcanic throat — another of those ragged upthrusts of black basalt that jutted out of the prairie here and there east of the Chuskas.

“Maybe he’s trying to paint something pretty,” Chee said. “Have you ever gone in there and taken a close look at it?”

Shirley shivered. “I wouldn’t go there,” she said.

“Why not?” Chee asked, knowing why. It probably had some local legend attached to it. Something scary. Probably somebody had been killed there and left his

chindi

behind to haunt the place. And it was tainted by witchcraft gossip. Delbert had been raised back in the Chuska high country west of here and he’d said something about that outcrop — or maybe one nearby — being one of the places where members of the skinwalker clan were supposed to meet. It was a place to be avoided — and that was part of what had fascinated Officer Delbert Nez with its vandalism.

“It’s not just that it’s such a totally zany thing to do,” Delbert had said. “Putting paint on the side of a rocky ridge, like that. There’s a weirdness to it, too. It’s a scary place. I don’t care what you think about witches, nobody goes there. You do, somebody sees you, and they think you’re a skinwalker yourself. I think whoever’s doing it must have a purpose. Something specific. I’d like to know who the hell it is. And why.”

That had been good enough for Chee, who enjoyed his own little obsessions. He glanced at his watch. Where was. Delbert now?

The door opened and admitted a middle-aged woman with her hair tied in a blue cloth. She paid for gasoline, complained about the price, and engaged Shirley in conversation about a sing-dance somebody was planning at the Newcomb school. Chee had another cup of coffee. Two teenaged boys came in, followed by an old man wearing a T-shirt with don’t worry, be happy printed across the chest. Another woman came, about Shirley’s age, and the sound of thunder came through the door with her. The girls chatted and giggled. Chee looked at his watch again. Delbert was taking too damned long.

Chee walked out into the night.

The breeze smelled of rain. Chee hurried around the corner into the total darkness behind the trading post. In the car, he switched on the radio and tried to raise Nez. Nothing. He started the engine, and spun the rear wheels in an impatient start that was totally out of character for him. So was this sudden sense of anxiety. He switched on his siren and the emergency flashers.

Chee was only minutes away from the trading post when he saw the headlights approaching on Route 33. He slowed, feeling relief. But before they reached him, he saw the car’s right turn indicator blinking. The vehicle turned northward, up ahead of him, not Nez’s Navajo Tribal Police patrol car but a battered white Jeepster. Chee recognized it. It was the car of the Vietnamese (or Cambodian, or whatever he was) who taught at the high school in Ship Rock. Chee’s headlights briefly lit the driver’s face.

The rain started then, a flurry of big, widely spaced drops splashing the windshield, then a downpour. Route 33 was wide and smooth, with a freshly painted centerline to follow. But the rain was more than Chee’s wipers could handle. He slowed, listening to the water pound against the roof. Normally rain provoked jubilation in Chee — a feeling natural and primal, bred into dry-country people. Now this joy was blocked by worry and a little guilt. Something had delayed Nez. He should have gone looking for him when the radio blacked out. But it was probably nothing much. Car trouble. An ankle sprained chasing his painter in the dark. Nothing serious.

Lightning illuminated the highway ahead of him, showing it glistening with water and absolutely empty. The flash lit the ragged basalt shape of the formation across the prairie to the south — the outcrop on which Nez’s vandal had been splashing his paint. Then the boom of thunder came. The rain slackened, flurried again, slackened again as the squall line of the storm passed. Off to the right Chee saw a glow of light. He stared. It came from down a dirt road that wandered from 33 southward over a ridge, leading eventually to the “outfit” of Old Lady Gorman. Chee let the breath whistle through his teeth. Relief. That would probably be Nez. Guilt fell away from him.

At the intersection, he slowed and stared down the dirt road. Headlights should be yellow. This light was red. It flickered. Fire.

“Oh, God!” Chee said aloud. A prayer. He geared the patrol car down into second and went slipping and sliding down the muddy track.

UNIT 44 WAS parked in the center of the track, its nose pointed toward Route 33, red flames gushing from the back of it, its tires burning furiously. Chee braked his car to a stop, skidding it out of the muddy ruts and onto the bunch grass and stunted sage. He had his door open and the fire extinguisher in his hand while the car was still sliding.