Craving (8 page)

Authors: Kristina Meister

* * *

I wanted rain. I wanted it to be like the movies, where there are slick black streets, rolling clouds of moody fog, umbrellas like sealskin, and a somber parade beneath a weeping sky.

It was seventy-five degrees and a bit muggy. The sun was forcing me to wear a pair of her sunglasses.

I thought there might be someone from her work, Moksha, or the woman from the night club, but no one came. I thought maybe she’d have a friend she’d kept from me because of the multi-purpose criticism I had in my back pocket like a Swiss army knife, but no. I thought even Unger might come, but I could feel him detaching himself from the grieving family and wondered if I’d ever hear from him again.

Instead of the crowd I’d wanted, it was just me, two ever-efficient gravediggers, and a man from the funeral home.

The casket was pearlescent. I picked it because as soon as I saw it, I thought of the tiny grain of ugly, annoying sand, mulled over and gnawed until it became something priceless, trapped inside a horribly plain shell.

There were no flowers. I didn’t need any symbols, those were for people who didn’t accept reality or were searching for meaning in something pointless.

“Would you like to say a few words, ma’am?”

I looked up at the man, thin, just the type of person who knew when to disappear. “No, thank you. Saying it now will make me feel less responsible, but it won’t change anything.”

He stared at me, but not in a confused way. I’m sure, as a man who was constantly comforting others he had seen a full spectrum of grief. Sobbing, saying farewell, raging at the universe were all old hat to me. I probably was as unmoved by it as he was, and I think he understood that.

“Shall I say a prayer?”

“No.”

Thankfully, he didn’t apologize or insist that something be done to commemorate the event. He smiled sympathetically and walked slowly back to the hearse.

“You can do it now.”

I watched them lower it in with their mechanized pulley. I gathered that they didn’t get many people who stayed to watch them work after enduring such defeat. They kept glancing at me, probably wondering if I’d throw myself onto the casket like Hamlet to take her into my arms once again. It reached the bottom with a soft, hollow sound and graciously, they walked away.

I looked at it, set in its shell, and felt nothing. The longer I looked, the less painful it became. It was an ending, just like the divorce. I almost felt relief and for that, I hated myself. They say that that’s what shock feels like, but I was pretty damn sure I’d had time to get over shock.

“Empty handed, I entered the world. Barefoot, I leave it,” said a voice.

Something in the way he said it kept me from seeking him out. She was most important at that moment. Like whispering an “Amen” at the end of a prayer or bowing the head at shame, I stood and waited for a reckoning.

“My coming, my going . . . two simple happenings that became entangled.”

I wanted to know more. A man who could come to think of all the pieces of his life as things that meant nothing to anyone but him, was a man whose life was interesting. That was the trick really. What made someone else sad was nothing to me, but that sadness was equal to any I would suffer. No one got away clean, so why acknowledge any of it? Life was just a blur bookended by two things a man would never remember about himself.

I looked up finally.

He stood where her headstone would eventually be, a book open in his hand. He wasn’t wearing black, but somehow that didn’t matter. His face had the smooth planes and high lines of Persian extraction, but his skin was no darker than a cup of tea with milk and had a golden hue in the sunlight. Thick, dark hair was smoothed into a ponytail; long, heavy lashes hid his eyes from me; full lips respected me enough not to smile in empathy no matter how badly the mind behind them wanted to.

“Excuse me?” I said lamely.

He closed the book and his fingers captivated my attention, but even as I marveled at how attracted I was, and why on earth I could be thinking of something like that at a time like this, I knew a certain amount of embarrassment. He was handsome, yes, but it was not the looks that mattered. It was the calm way he stood. It was the graceful way he both came near me and yet kept his distance from my thoughts.

He could not be a man constantly surrounded by death or the miseries of others, but someone living behind a big wall, listening to hymns, reading metaphysics. He had a presence, and though I’d always heard people talk about that kind of thing, I had never before felt it.

In a moment of disquiet, I could have sworn I knew him, but I was positive that if I had ever seen someone like him, I would have remembered it clearly. It felt strange to be so enthralled, just that quickly.

His eyes lifted with the corners of his mouth. They were blue like the sky and gave him an exotic look. “A Japanese poem, written by a Zen master at the moment of his death.”

His arm moved away from his body casually and the book landed on top of Eva’s casket. Then, he turned and started for the large, iron gate to the cemetery, walking as if he really had no reason to be going anywhere in particular. Something about that demeanor made me think that he might not mind if I admitted not wanting to be alone for once.

“Excuse me?” I called after him, cringing that I hadn’t put my years of crossword puzzles to better use.

What was a five letter word, beginning with “I,” for an incredibly stupid individual who tripped over her own thoughts as they rolled off her tongue?

“Did you know my sister?”

To my amazement, though, he turned and strangely, even though he seemed relaxed, the glance over the shoulder did not come off as austere. He looked at me as if he had to be sure I could understand him when he spoke.

“Did you?”

Taken aback that he could be callous while seeming so genteel, I stared after him blankly as he walked toward the street. One of my chief regrets in my life thus far was my temper, but even though I tried to manage it, it somehow always took hold of my spine and operated my limbs like a remote control car. I chased after him, forgetting all about the pearl in the ground.

“Excuse me?” I asked angrily, and to my credit, it

did

come out sounding different from all the other times.

He stopped in his tracks and the proximity warning in my mind beeped until my anger management issue got fed up and stormed off. I came to an abrupt, lurching halt and waited to see what he’d do.

“It’s all there, you know,” he said with a sigh. “Every answer you’ve ever wanted, but sometimes it’s the reason for asking that is the most questionable thing.”

I couldn’t say it a fourth time, I was sure that was far too many, so I settled for, “What?”

“The only way you’ll see the answer, is if you already know what’s important to you.”

“A lot of things are important to me,” I defended, and instantly heard my petulance.

He shook his head. “Do you love the sadness you feel, to protect it so viciously?”

I scowled at his back. “Everything that meant anything to me is dead. How about you let me grieve in peace?”

He turned around completely and once again, looked through me.

“You had her within reach for so long and never once asked how she felt, what she knew, who meant the most to her. Now she is gone forever. You do not grieve for her, but for the lost chance.”

His honesty cut through me to the core. For some reason, I felt insanely angry that anyone could question my devotion to her, even as I was there cleaning up her final mess.

“She hated everything, thought that the world was out to get her, and only cared about herself! She was the guilty one,” I shouted at him, a

real

total stranger, who probably hadn’t even met Eva and was just being nice in some twisted way.

“You speak so of someone you loved?”

And then it hit me. I

did

hate her, not for leaving me, but for making me do the heavy lifting, for relying on me to be the person I was. I was mad at her when she had given up everything. What the hell was wrong with me?

“What is this?” I said under my breath, but somehow, he heard me. “What the hell is wrong with me?”

He smiled and passed through the gate to continue on his way. “‘Coming, all is clear, no doubt about it. Going, all is clear, without a doubt. What, then, is ‘all?’”

Chapter 7

I thought about the stranger’s words for the rest of the day. They kept repeating in my mind, overlapping what Unger had said about accepting that everything ended eventually. It wasn’t about why I was asking; it couldn’t be. I

knew

why I was asking, and even if it was a shitty reason, I

already knew

. Yes, it was because

I

felt badly, but so what? Should I feel badly about that too? Should I hate myself because hindsight was twenty-twenty, or should I simply seek out the truth that made me comfortable?

If there was someone else to blame, then it couldn’t be my fault and I wasn’t the horrible sister I’d never set out to be.

It wasn’t her home, her life, or her misdeeds that I was hunting anymore. I was taking them over and soon, they would bear my mark. Or leave their mark on me.

I sat in the happy face, staring at her bookcases: four rows of black, one row of blue, two volumes of green, and a long row of fat, red tomes. There had to be a significant reason they were divided, but there was nothing to distinguish them from each other except their bindings.

Never judge a book by its cover.

I pulled out the black book I had gone through before and flipped through its patchwork pages. Her feelings, long essays on the meaning of life, sketches, and even a few song lyrics crowded there. I set it down and picked out one of the green books. This was entirely different. It contained numbers in columns and rows like a ledger, but what the numbers meant was not indicated in any kind of legend. Some had obvious markers like “lb” or “$,” but there were no totals, or any kind of averaging. Confused, I set it aside and went for the last blue volume. Lists, dates and locations; it was an appointment book. I flipped to the last entry and promptly dropped the volume as if stung.

“August 9

th

Top of the Old River Motel

Goodbye, Lily.”

My vision darkened over the fat, red pen strokes.

“Bye, Ev,” I whispered.

My fingers shot out for the last red volume and felt around blindly. I could see nothing through the distortion of my tears. The book was heavy, and when I dropped to my knees and lay it on the floor, it almost refused to open. I turned the pages as if looking for an emergency phone number, until I realized that the blurry images there were neat and tidy, unlike anything else I had seen from her. Row after row, stanzas like poems, but none of it made any sense. It rhymed in some places, had a definite rhythm, but some of the words were gibberish and not a single line was a complete sentence. It was the same all the way through, until I found the symbol.

Scrawled in the same red sharpie as her appointment with Death was the neon sign from above the nightclub door.

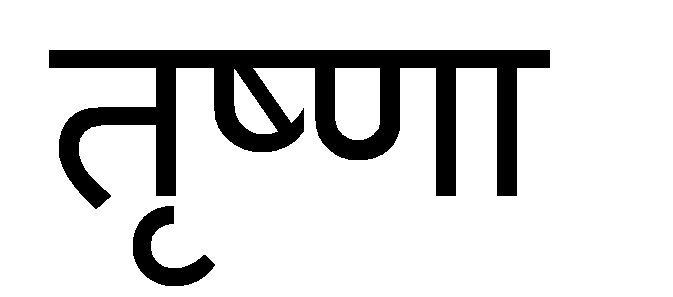

I looked at it closely for some time, trying to pick out what language it might be. It looked as if it was some kind of Middle Eastern dialect. I looked around the room blankly and recalled that my sister had no computer.

I grabbed the four books I had pulled from the shelves and threw them into a backpack I found in her closet. I raced down the stairs to the street and jumped into my car. After the push of a button on its dash, now thankful they had been out of plain old Hondas, I barked orders at the friendly lady who happened to pick up my signal.

“Directions to an Internet Café.”

She helpfully stuffed them into an electronic envelope and before long I was driving through dark streets toward an answer. When I had paid the exorbitant fee and logged onto a terminal, I rifled through servers until I found what I was looking for, a dictionary of Sanskrit. When I found it, though, I didn’t know where to start. I couldn’t search by the symbol on the paperweight I was using and I couldn’t go by the Sanskrit word itself, because I couldn’t actually read it. Annoyed, I went through the lists of words, just looking for anything I recognized. Letter by letter, I searched, muttering to myself as I scrolled, but when I came to “M” everything changed.

“Moksha,” I read aloud, “liberation from Samsara, the cycle of death and rebirth.” With an aggravated hiss, I sat back. “That arrogant, stuck up prick.”

I wondered if it was his real name. He certainly didn’t look like he was someone who might speak Sanskrit; after all, as the webpage told me, it was the root language of the Indian dialects and an ancient cousin of Latin.

I reached into the pack and pulled out the red volume. On the marked page, I examined the stanzas. It had to be some kind of code, but I didn’t know anything about codes. I could connect one or two of the words together by counting every fifth word, or second word, but nothing made complete thoughts.