Crazy Horse and Custer: The Parallel Lives of Two American Warriors (36 page)

Read Crazy Horse and Custer: The Parallel Lives of Two American Warriors Online

Authors: Stephen Ambrose

Tags: #Nightmare

CHAPTER THIRTEEN

Crazy Horse and the Fort Phil Kearny Battle

“With eighty men, I can ride through the entire Sioux nation.”

Captain William Fetterman

In the spring of 1866 the red-white crisis on the northern Great Plains began to move toward a climax. Crazy Horse, newly appointed as a shirt-wearer, faced the most significant challenge of his career as a military leader. He and his comrades were determined to keep the white man out of the Powder River country, which meant they had a defensive mission—to protect the boundaries of their hunting grounds. But because Crazy Horse and the Oglalas failed, in the summer of 1866, to prevent the whites from establishing a fort in the heart of their territory, they were on the defensive only for strategic purposes; in their tactics they necessarily assumed the offensive. Red Cloud provided the over-all leadership for the ensuing campaign, one of the most impressive in the annals of Indian warfare, while Crazy Horse served as one of his field commanders, directing the day-to-day tactics in dozens of skirmishes and fights. Crazy Horse was as successful in his role as Custer had been as a combat leader in the Civil War.

Also, as had been true in Custer’s case, Crazy Horse was lucky in his opposition. The whites were divided on the question of how to carry out a campaign against the Sioux, indeed, on whether or not to even undertake a military campaign to clear the northern Plains of the troublesome red men. The United States was war-weary. People had had enough—enough of slaughter, of conscription, of war-encouraged corruption, of the cost of war, of war news generally. The Civil War Armies had been demobilized, the fighting strength of the nation dissipated. Of those few troops left, most were needed for occupation duty in the southern states.

The whites had turned their attention away from war and back to the real business of the nation: expansion. The South was defeated and demoralized, but the triumphant North was bursting its britches,

full of swagger, ambitious plans, grandiose hopes. The two questions that had plagued the nation since its founding, slavery and the nature of the Union, had been settled on the field of battle. Now that the South had been reunited with the North, it was time to spread the American eagle over the whole continent, bringing the Far West into contact with the remainder of the nation by conquering the Great Plains and then crisscrossing them with railroads that would tie the Union together and complete the task begun in the Civil War.

Nowhere was the dynamic quality of post-Civil War America seen more clearly than in the various projects to span the Plains with continental railroads, nor did any other project so completely reflect the national purpose or so thoroughly capture the imagination of the American people. In the spring of 1866 the progress of the Kansas Pacific (which by then had reached Manhattan, Kansas, 115 miles from the Missouri), the Union Pacific (194 miles west of Omaha, at Fort Kearney, Nebraska), and the Central Pacific coming from California to meet the Union Pacific (tearing at the summit of the Sierra Nevada) were topics of daily discussion and achievements in which Americans took deep pride. The Army protected the railroad builders from marauding Indians, and the railroads had no better friends than the Army officers, especially Major General William Tecumseh Sherman, in St. Louis, in command of the Department of the Mississippi, a vast domain stretching from the Mississippi River to the crest of the Rocky Mountains.

1

“I hope the President and Secretary of War will continue, as hitherto, to befriend these roads as far as the law allows,” Sherman wrote his superior, General Grant, in the spring of 1866. As for the Army, “it is our duty … to make the progress of construction of the great Pacific railways … as safe as possible.”

2

With good reason, Sherman feared that the Army would not be allowed to show that it could do to the Indians what it had done to the rebels. The Radical Republicans had inaugurated a peace policy for the Plains tribes, their idea being, as noted above, that it was cheaper to buy a way through the Plains than to fight a way through, and easier on the national consciousness. Putting the Sioux and other tribes on welfare certainly would have been cheaper, had it worked, but the government was miserly in its offers. Crazy Horse, Red Cloud, and the other Indians had no head for figures, but they could recognize a bad deal when they saw one. The government was offering $15,000 annually in annuities for a tribe of 5,000 or 6,000 people, hardly a sum sufficient to provide for their real necessities.

Each individual Sioux would get from his annuities less than he could secure from a trader for a single buffalo robe.

3

Here was the real tragedy of the Plains wars. The peace-policy advocates, so much scorned by nearly every white Westerner at the time and by almost all historians who have written on red-white relations, were in fact victims of a governmental determination to cut taxes, lower expenditures, and balance the budget. A genuine offer to the Indians of nicely located, adequately supplied reservations, with sufficient annuities, would have attracted the bulk of Red Cloud’s and Crazy Horse’s warriors away from the Powder River country and out of the path of the advancing railroads. Expenditures of a quarter of a million dollars annually might have done the trick. Instead, the government tried to get by with $15,000 annually. And when that did not work, the Army had to spend millions subduing the hostiles. Red Cloud, Crazy Horse, and the other Indian leaders who were determined to resist white encroachment no matter how high the bribes went were the principal beneficiaries of the government’s balanced budget, for it kept the Sioux moderates on their side.

Governmental blunders were constant. The route of the Union Pacific, which generally followed the Oregon Trail, had already been cleared of hostiles, while the Army was blasting a path through the central Plains for the Kansas Pacific. That left only the Powder River Sioux as obstacles to westward expansion, but in the spring of 1866 those Indians were bothering only the Crows. There were no white settlers in their area and the Northern Pacific was years away from entering their territory. It was true that they controlled the shortest route to the Montana mines, the Bozeman Trail, but they had been allowing whites to proceed along the trail just as they allowed emigrants to use the Holy Road years earlier. Miners on their way to Montana would give the Sioux some coffee and sugar, then go their way in peace. The Montana Historical Society has preserved a number of diaries of men who traveled the Bozeman Trail at this time, and they all indicate that there were relatively few difficulties with the Indians.

4

The United States Government had an obligation to protect its citizens, to be sure, but not when they did not require protection. It certainly had no obligation to provoke a crisis, but it did when it allowed the Army to carry through with plans to establish forts in the heart of Oglala Sioux territory.

The Army could be as stupid as the government. Badly under-strength following the demobilization, the Army already had more tasks than it could handle. It was in no way prepared to send a

sizable force into the Sioux country to cow or conquer the hostiles, nor was there any need to do so. Nevertheless, the Army did build the forts. Under the circumstances, it is difficult to avoid the conclusion that Grant, Sherman, and their associates wanted to deliberately provoke the Sioux into an all-out war, which the Army believed would lead to the extermination of the Sioux and thus a “final solution” to the Indian problem. Having conquered the Confederacy, the United States Army officers were full of optimism. They had, in short, made the classic military blunder of underestimating their enemy.

Sherman’s policy in 1866 was based on his

idée fixe

that the initiative belonged to the Army. In the early summer of 1866, after starting minuscule forces on their way into the vast area of the Powder River country with orders to establish forts along the Bozeman Trail, Sherman wrote Grant’s chief of staff, “All I ask is comparative quiet this year, for by next year we can have the new cavalry enlisted, equipped, and mounted, ready to go and visit these Indians where they live.”

5

To make matters worse, Sherman assigned the command of the newly created “Mountain District” to a garrison officer with no experience in Indian warfare, Colonel Henry B. Carrington, and gave him a tiny force that consisted almost entirely of raw recruits.

6

Sherman evidently believed that the Indians would sit and watch while he established forts, reorganized the Army, raised new cavalry regiments for Indian warfare, and then attacked the Sioux in their villages at a time of his own choosing.

The campaign began in the spring of 1866, when Sherman started Carrington’s column marching up the Holy Road toward the Powder River, while E. B. Taylor of the Indian Office called the Sioux to a council at Fort Laramie. Taylor was a leading advocate of the peace policy. By promising plenty of presents, including some arms and ammunition, he had induced the friendly chiefs to sign a treaty giving the whites the right to use the Bozeman Trail. Now he wanted to sign up the hostiles, so he sent runners to their camps to tell them that there was a rich store of presents awaiting them at Fort Laramie. Crazy Horse and most of the younger warriors did not want to go. They argued that the Oglalas and other tribes were living fat and had no need of the white man or his presents. But Red Cloud, the older chiefs, and Young Man Afraid decided it would do no harm to see what Taylor had to offer, the chief inducement being the possibility of getting arms and ammunition, always in desperately short supply among the Indians.

So Red Cloud and Young Man Afraid made the journey to Fort Laramie, leaving Crazy Horse and the warriors who were unwilling to consider compromise behind. When the delegation arrived at Fort Laramie, Red Cloud immediately demanded that Taylor explain to them, in detail, what the white men wanted. Taylor deliberately attempted to deceive them; he said nothing about the Army’s building forts and declared that the whites wanted nothing new, only a legal right to use the old road, meaning the Bozeman Trail. He was upping the ante, too, offering $75,000 in yearly annuities, or about $10 per Indian, plus guns for hunting. The white travelers would not disturb the Indians’ hunting grounds, Taylor promised, nor in any other way disrupt their way of life. All they wanted was free passage on the old road.

This was strong inducement indeed—guns and ammunition in return for simply touching the pen—and Red Cloud might have signed. But just at the critical moment, when he was wavering, a Brulé chief named Standing Elk came to Fort Laramie with the news that Colonel Carrington and his column of troops were a few miles away to the east. Standing Elk said that he had talked with Carrington, who casually informed him that the soldiers were marching to the Powder River, where they were going to build forts and guard the new road. The Brulé chief informed Carrington that “the fighting men in that country have not come to Laramie, and you will have to fight them.” Standing Elk then rode on to Fort Laramie, where he told Red Cloud what had happened.

Wrapping his robe around him in a dramatic gesture, holding his head high, his eyes blazing, Red Cloud declared, “The Great Father sends us presents and wants us to sell him the road, but White Chief goes with soldiers to steal the road before Indians say Yes or No.” He stormed out of the council tent, followed by Young Man Afraid and the other hostiles.

7

That left Taylor and the friendlies. He got them all to sign up again, an unnoteworthy accomplishment if there ever was one, then telegraphed Washington, “Satisfactory treaty concluded with the Sioux. … Most cordial feeling prevails.” He mentioned Red Cloud only in passing, saying he was an unimportant leader of a small group of malcontents. The government really believed it had peace on the Plains. Early that winter, on the eve of one of the worst defeats in the history of the U. S. Army, President Johnson assured the nation that the Sioux had “unconditionally submitted to our authority and manifested an earnest desire for a renewal of friendly

relations.”

8

The Army was more realistic but Sherman allowed Carrington to proceed under the impression that there would be no conflict on the Plains until the Army initiated it.

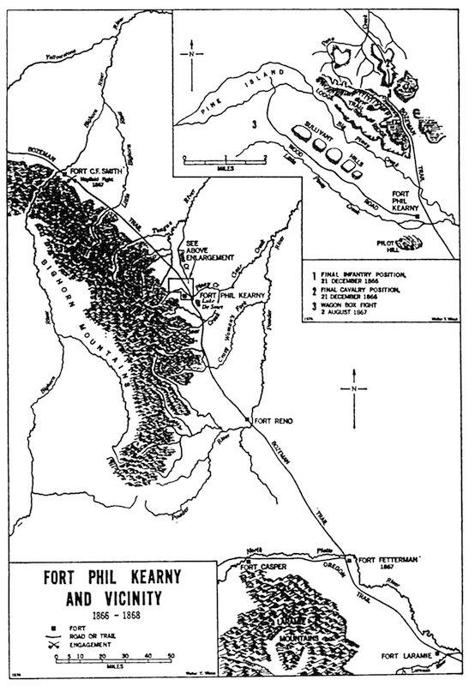

Carrington proceeded to Piney Creek, just northwest of Lake De Smet and about half-way between the Powder and Bighorn rivers, on the eastern foothills of the Bighorn Mountains. There he built Fort Phil Kearny. On August 3, 1866, he detached two of his seven infantry companies, sending them on north along the Bozeman Trail to establish Fort C. F. Smith on the Bighorn River near the point where the river cut its way out of the mountains. That left Carrington with 350 soldiers to guard a hundred miles of the Bozeman Trail.