Authors: Candace Savage

Crows (5 page)

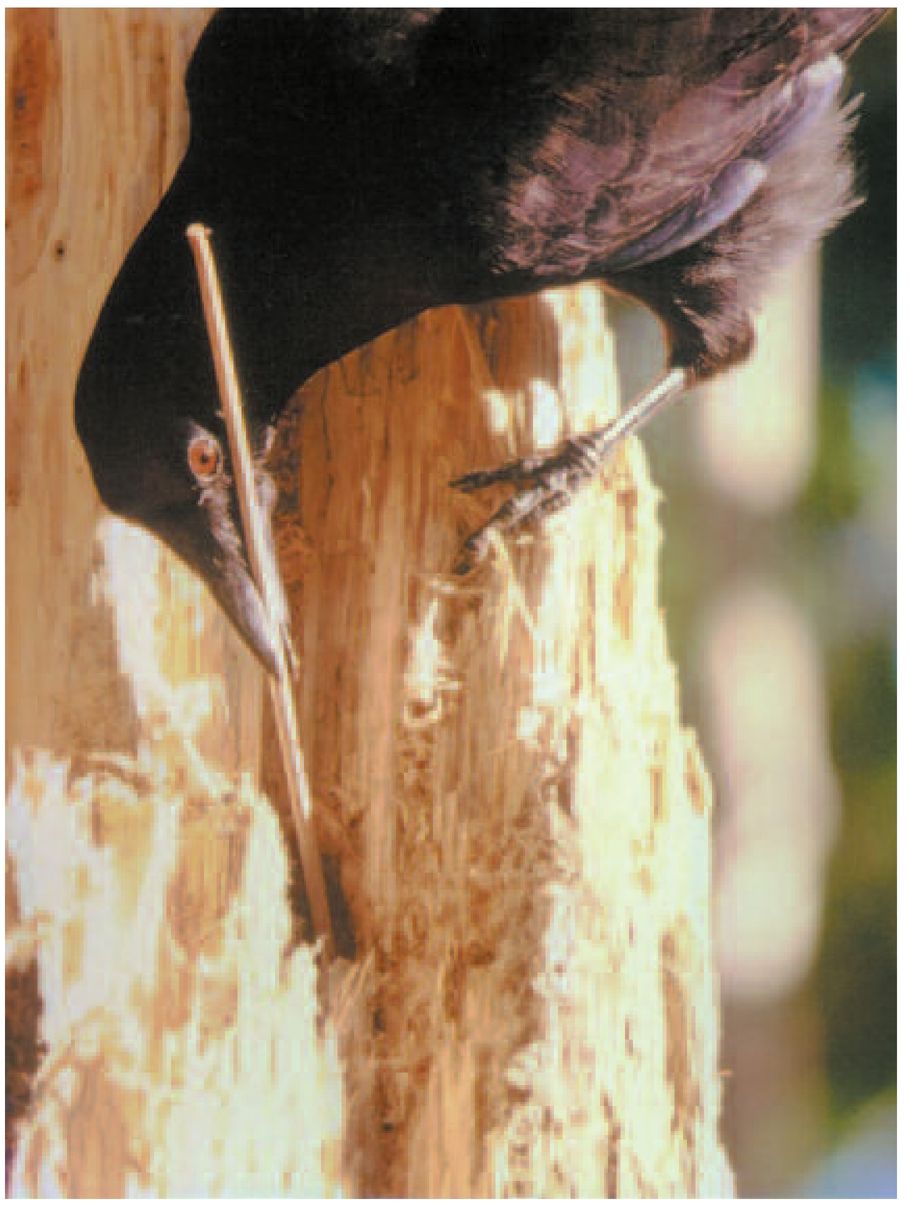

In this extraordinary photograph by researcher Gavin Hunt, a wild New Caledonian crow uses a stick tool to investigate a crevice in a tree trunk.

In this extraordinary photograph by researcher Gavin Hunt, a wild New Caledonian crow uses a stick tool to investigate a crevice in a tree trunk.But most impressive of all is the New Caledonian crow, one of perhaps two nonhuman species—the other possibly being the chimpanzee—in which

all

individuals in

all

populations routinely make and use simple technology. (The roster of toolmaking animals also includes orangutans, African and Asian elephants, and the woodpecker finches of the Galapagos, but their tool use is restricted to geographically defined groups.) New Caledonian crows are also exceptionally versatile toolmakers, producing not just one but several kinds of implements. In addition to making probes from twigs, both with hooks and without, they also manufacture finely crafted “stepped” tools from the stiff leaves of the pandanus tree. Working delicately with the sides of their bills, clipping and tearing by turns, the birds cut out shapes that look like half of a skinny Christmas tree as seen in a child’s drawing. One side is left straight, while the other is cut to a sharp point at the top and then widened out in steps toward the bottom. This design combines a fine tip for probing with a broad base for stability and ease of handling. As a final touch, the birds also ensure that natural barbs found along the straight side of the leaf-tool curve downward from top to bottom so that they can be used to rake insects out of crevices.

all

individuals in

all

populations routinely make and use simple technology. (The roster of toolmaking animals also includes orangutans, African and Asian elephants, and the woodpecker finches of the Galapagos, but their tool use is restricted to geographically defined groups.) New Caledonian crows are also exceptionally versatile toolmakers, producing not just one but several kinds of implements. In addition to making probes from twigs, both with hooks and without, they also manufacture finely crafted “stepped” tools from the stiff leaves of the pandanus tree. Working delicately with the sides of their bills, clipping and tearing by turns, the birds cut out shapes that look like half of a skinny Christmas tree as seen in a child’s drawing. One side is left straight, while the other is cut to a sharp point at the top and then widened out in steps toward the bottom. This design combines a fine tip for probing with a broad base for stability and ease of handling. As a final touch, the birds also ensure that natural barbs found along the straight side of the leaf-tool curve downward from top to bottom so that they can be used to rake insects out of crevices.

How do mere birds create such intricate artifacts? Are the crows mindless robots, programmed by their DNA, or could they really be as smart as they seem to be? Or perhaps they are genetic-brainiac combos, with both an innate talent for toolmaking and a mental bent toward design and invention. Nobody knows for sure. But researchers have discovered that, for their size,

crows are among the brainiest organisms on Earth, outclassing not only other birds (with the possible exception of parrots) but also most mammals. In fact, the brain-to-body ratio of a typical crow is similar to that of a chimpanzee and not far off our own. And just as we and other primates have a large prefrontal lobe, the presumed seat of our higher intelligence, so crows also have exceptionally large forebrains that may serve a similar function. Could it be that the evolutionary challenges that encouraged our own ancestors to amass all those little gray cells also pushed the ancestral crows to grab a brain for themselves?

crows are among the brainiest organisms on Earth, outclassing not only other birds (with the possible exception of parrots) but also most mammals. In fact, the brain-to-body ratio of a typical crow is similar to that of a chimpanzee and not far off our own. And just as we and other primates have a large prefrontal lobe, the presumed seat of our higher intelligence, so crows also have exceptionally large forebrains that may serve a similar function. Could it be that the evolutionary challenges that encouraged our own ancestors to amass all those little gray cells also pushed the ancestral crows to grab a brain for themselves?

At Oxford University in England, a team of scientists led by zoologist Alex Kacelnik has recently begun to investigate these provocative questions. As a first step, the researchers have established a captive colony of New Caledonian crows in their laboratory and are designing experiments to test the birds’ understanding of basic physics. To date, the star of this project is Betty, a young female crow who was caught in the forests of Grande Terre island, New Caledonia, in March of 2000. Once settled into her new accommodations—a room with a large outdoor aviary that she shared with another crow, called Abel, a male of unknown age who was acquired from a New Caledonian zoo, Betty quickly began to show the world what she could do.

In one series of trials, for example, she was presented with the challenge of obtaining food—pig’s heart, her favorite—by poking a stick through a small hole in a plug. The trick was to insert the stick through the hole and use it to push a food cup along a tube to a downward elbow bend, where the cup would fall out onto the table and the food could be eaten. Provided with several tools of different diameters, including some that were too large for the hole, Betty always chose the smallest one available. She did so even if her pesky keepers tied up her preferred tool with a bunch of other sticks, just to make things more interesting. Not once did she select a tool that was too big to fit. And when she was provided with a branch from an oak tree and allowed to manufacture tools for herself, she almost always produced probes that were the right size for the task. If the hole in the plug was large, she produced large sticks; if the hole was narrow, she kept on whittling.

“Little by little does the trick” in this drawing by Richard Heighway, 1896.

“Little by little does the trick” in this drawing by Richard Heighway, 1896.The CROW and the Pitcher

FROM

AESOP’S FABLES,

SIXTH CENTURY BC

AESOP’S FABLES,

SIXTH CENTURY BC

A

thirsty Crow found a Pitcher with some water in it, but so little was there that try as she might, she could not reach it with her beak, and it seemed as though she would die of thirst within sight of the remedy. At last she hit upon a clever plan. She began dropping pebbles into the Pitcher, and with each pebble the water rose a little higher until at last it reached the brim, and the knowing bird was enabled to quench her thirst.

thirsty Crow found a Pitcher with some water in it, but so little was there that try as she might, she could not reach it with her beak, and it seemed as though she would die of thirst within sight of the remedy. At last she hit upon a clever plan. She began dropping pebbles into the Pitcher, and with each pebble the water rose a little higher until at last it reached the brim, and the knowing bird was enabled to quench her thirst.

Moral: Necessity is the mother of invention.

This fifteenth-century Hungarian coat of arms features a crow brandishing a twig.

This fifteenth-century Hungarian coat of arms features a crow brandishing a twig.In another experiment, both Betty and Abel also demonstrated an understanding of length. Given a selection of tools to choose from, some too short to reach the cup, they usually picked out a stick that was long enough. In twenty trials, Betty made the wrong choice on only five attempts, and Abel scored an impressive 95 percent. But the most exciting experiment of all was one that the crows set up for themselves. In this case, food had been placed in a little bucket at the bottom of a transparent tube, from which it could be removed

only by reaching down and snagging the handle of the bucket with a hooked tool. A selection of wires was provided for the birds, some straight (and therefore presumably useless) and some hooked (just right for the task), and the researchers stood by to see how the birds would respond. In the first few trials, everything went as expected, as the crows sized up the situation and figured out what to do. But in the fifth run-through, Abel added an unexpected variation by picking up the only hooked tool in the room and flying away with it, leaving Betty with nothing to work with but a straight length of wire.

only by reaching down and snagging the handle of the bucket with a hooked tool. A selection of wires was provided for the birds, some straight (and therefore presumably useless) and some hooked (just right for the task), and the researchers stood by to see how the birds would respond. In the first few trials, everything went as expected, as the crows sized up the situation and figured out what to do. But in the fifth run-through, Abel added an unexpected variation by picking up the only hooked tool in the room and flying away with it, leaving Betty with nothing to work with but a straight length of wire.

Although Betty had often been given wire tools to use, she had never made them herself and had never even had an opportunity to see wire being bent. Nonetheless, she flew over to the tube and peered at the food from various angles. Then, in less time that it takes to describe it, she picked up the wire, stuck one end under a piece of tape at the base of the apparatus, and, pulling back with body and bill, bent it into a hook. Down the tube it went, through the handle, and voilà, dinner was served. When the researchers recovered from their amazement, they ran a series of trials in which Betty was challenged to repeat her accomplishment, and, although she did not always produce perfectly rounded hooks, she always succeeded in bending the wire and hoisting up the food. The great Raven himself couldn’t have done it better. No other animal—not even a chimp—has ever spontaneously solved a problem like this, a fact that puts crows in a class with us as toolmakers.

Other books

Call of Kythshire (Keepers of the Wellsprings Book 1) by Missy Sheldrake

Green Algae and Bubble Gum Wars by Annie Bryant

Bloody Lessons by M. Louisa Locke

ROOK AND RAVEN: The Celtic Kingdom Trilogy Book One by Delcourt, Julie Harvey

Doomsday Love: An MMA & Second Chance Romance by Shanora Williams

Leaving by Karen Kingsbury

Melody (THE LOGAN FAMILY) by Stacy-Deanne

The Warrior Vampire by Kate Baxter

Dirty White Candy, The Beginning, Book 1 by Cox, Anita

The Village Witch Doctor and Other Stories by Amos Tutuola