Cuba 15 (12 page)

Forestfield High School took the team trophy; they’d had six finalists. Leda punched me when all six of them trooped up to accept the trophy, raising their water bottles in victory.

“Evian High!” she said with disgust.

So this was how losing felt.

The lump in my stomach settled in for the long haul as our team headed for the bus. I forgot to count the Magikist sign on the way home.

19

My critiques from the judges varied. I had placed third out of nine in my first round, and the judge had remarked on the sheet, “Good topic—original! How about some more dialogue?”

In my bumbling second performance, I’d come in seventh. There had only been seven O.C.s. That meant I was worse than the guy who’d spoofed a television wrestling match, and nobody had laughed at him. The judge’s suggestion to me? “Try to memorize your lines.”

Yes, I would. Yes, I would.

Mr. Soloman possessed the good grace to say only, “Next time, girl,” on our way off the bus. I figured he was saving the yelling for later.

So I was feeling low when I got home and slouched into the kitchen through the side door. Mom sat at the table, writing, while Chucho stood at his bowl, chunking down his dry food without chewing.

“How’d you do, hon?” Mom asked me, not taking her eyes off her notebook. She was working on restaurant plans again.

“Okay,” I said. “I came in third.” Which was true, sort of.

“That’s nice . . .” She finished the sentence she was writing and set her WBEZ pen down. “How about this one, Violet? I was up all night thinking about it: a drive-through bakery specializing in breads.” She paused, waiting for me to ask.

“Let me guess. ‘A Moveable Yeast’?”

“Close, but no cigar. I call it ‘Catch ’er in the Rye’!” She waited a beat.

“HA!”

she prompted, and when I didn’t join in, she gave three halfhearted shakes.

These titles were getting so bad, she should’ve been naming hair salons. I said as much, then wished I could immediately take it back when Mom replied, “Hmmm. D’you think so?”

I threw up my hands. “Who cares what the theme is? If you’d ever stick to one thing, Mom, maybe you’d actually

open

a restaurant.”

Bold words directed at my

quince

captain of strategy. But Mom wasn’t mad. She cut her eyes at me, and this time I saw her hypothetical plans fall in one swoop, like a house of cards. After my devastating theatrical loss, I just couldn’t leave it at that.

“Plans aren’t everything, Mom,” I said, and left the kitchen.

The seasons had changed. September had given us a final warm clap on the back and let the screen door bang on its way out. October stirred a familiar stew of drizzle and autumn leaves. In neighboring Wisconsin, bold flaxen, persimmon, and cherry-colored foliage drew dull Illinois drones like hungry bees. But here on my corner of Woodtree Lane, all the leaves had turned a sallow yellow and threatened to drop with the next breeze.

Chucho enjoyed the wet and decay of the sparse piles that drifted up against the curbs on our daily walks, while I was just a shuffling lump on the other end of the leash. I kicked limply at the brown and yellow curls on the sidewalk, biding my time until the first snowfall, and the ones after that. To ski, or not to ski.

For now, it was speech season. I had to tell Mom no when she asked if I wanted to drive up to the Wisconsin Dells with her and a friend on Saturday to look at the trees, because of rehearsal. Vera Campbell and I were supposed to coach each other, and I heard that all the Extempers would be there too, working on their files. This interested Leda enough that she was going to skip a lucrative Greenpeace event to come to school.

I knew I’d have plenty to do. Following the Taylor Park tournament, Mr. Soloman had videotaped my routine and sat me down in C206 in front of a television to dissect it.

The agony.

Now I knew why some actors refuse to watch their own movies. My six-and-a-half-minute performance took on all the hallmarks of the Chinese water torture: There I stood, blabbing on and on about my boring family, managing to make even the conga line and the burning roast seem boring. How could I ever have thought any of this was funny? By the time I begged the police to take me away, please, the audience must have heaved a huge sigh of relief.

Mr. Soloman just left the tape running and looked at me through his glasses.

“I . . . guess you had to be there?” I mumbled.

He thought a moment.

“I guess

you

had to be there.” He motioned for me to get out of my seat and led me down front.

“Violet, remember when I showed you that sea ostrich speech on tape?”

I nodded. That one was starting to look good in retrospect.

“What was it that we both agreed was wrong with that piece?”

Our conversation came floating back to me. “Too much narration. The guy never gave any other point of view but his own.”

Mr. Soloman nodded. “I think that’s what we’re seeing here.”

I felt the stab of truth, then a flash of anger. He could have told me this sooner. “Then why’d you let me compete with it?”

He smiled at me like Glinda the Good Witch. “You had to learn it on your own. Now, forget about last week. Watch me.”

I moved back a few paces, and he began my speech. Knew the lines better than me: “The story you are about to hear is true,” he deadpanned. At the end of the intro, he stopped. “Here is where you make the big shift. The monotone works to draw the audience in with mock seriousness. Then you want to surprise them—wow them—with your first character. Now, your turn.”

“You mean,

do

the characters?”

He nodded again. “You’ve got all the funny elements in there, Violet. Bring them out.”

I improvised a dialogue between Abuela and Marianao, changing my voice for each character.

“Not bad,” Mr. Soloman said, stopping me. “But think

big

. Exaggerate the hand motions. Throw in an imaginary prop or two. And don’t look at me when you’re in character—pick your focal points. Try it again,” he commanded.

This time I had Abuela do a little dance around an imaginary Chucho, who was trying to eat the buckles off her imaginary shoes, and I threw in Marianao’s cigar.

I looked up to find Mr. Soloman laughing. Hard.

When I finished, he was still smiling. “That cigar! Did you make that up?”

“Uh, yeah,” I lied, a narcotic glow spreading through me. I was starting to feel like I’d do anything for a laugh, it felt that good. I suddenly understood comedy acts like the Three Stooges, and Abbott and Costello. Even the film

Dumb and Dumber

took on a new sheen; no wonder Jeff Daniels and Jim Carrey had done it.

“That’s great,” Mr. Soloman said.

He walked me through the rest of my routine, making suggestions here and there. Pantomiming the conga line was a challenge, but I was beginning to see the light. Be funny. Why hadn’t I thought of that before?

My great brainstorm hit as we were wrapping up for the day. Mr. Soloman had said to take what I knew about how competition rounds worked and apply it to my presentation. I remembered how deathly quiet the classrooms had been during rounds. If I could shock the audience out of that silent cocoon, I’d get people’s attention, all right.

“Hey, Mr. S.! Remember that Superbaby routine? How the guy starts out with that horrible baby cry?”

“Yeah. So?”

“What about . . . if I do something like that? I could have the police chase me up to the stage!”

“With a siren blaring,” he put in. “That would really tie your theme together—sentenced to life!” He unplugged the video monitor and started winding up its cord. “Work on it, and show me next time. Rolling Fields tourney is in two weeks.”

“Who’s on first?” I asked, hoping it would be me.

“Huh?”

“No, Huh’s on second, Who’s on first,” I said, jogging up the ramp between the tiers of seats. “See you next Tuesday, Mr. S.!”

I slowly added ideas to the

quince

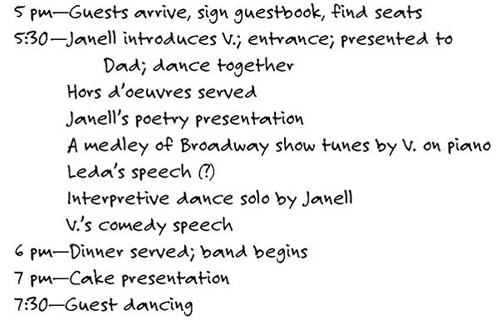

notebook. The big day was on a Sunday. While we weren’t inviting anyone to a special church service, Mom and Dad and I had decided our family would attend regular Mass at St. Edna’s that morning, for posterity, and then get ready for the party. I had nearly finalized the lineup for the “All the World’s a Stage” show:

That ought to do it. By the time the party was over, I’d be a woman. Or at least I hoped so, for Abuela’s sake. I showed my

damas

the outline one day after school as we hung out by Janell’s locker.

“I’m supposed to give my speech?” Leda asked, surprised. She and Janell had received mixed reviews at the tourney too. “You want ‘Plows, Not Cows’?”

“This isn’t a rally,” Janell remarked.

“Yeah, can you try and come up with something to go with ‘All the World’s a Stage’?”

“And not ‘All the World’s a Cage,’ either,” warned Janell. “Guests will be eating meat, and we don’t want to freak them out.”

“Yeah,” I said, “we’re serving some of those bacon-grease ice cream cones, and we want everybody to enjoy them.”

Leda clapped steely eyes on me. “

Don’t

mention that.”

Janell fought to keep her trembling lips in a straight line.

“Sorry,” I lied.

Leda ignored me as she cranked up the gears and pulleys in her head. She was on a trail, as the Extempers called it. “I’ll think of something,” she mused. “After last week, I might try another event. Declamation, maybe. At least Dec speeches are written by somebody else.”

“Well, hurry up. I’ve only got another six months before I’m supposed to be a woman.”

Leda eyed my still sunken chest. “You’d better start exercising, then.”

20

When Vera and I met on Saturday afternoon to rehearse, we found an invitation taped to the door of Room C206. In wiggly, scary-type letters, the sign read, “ARE YOU AFRAID OF THE DARK? Scared of screams? Terrified by great food, music, and costume judging? Come to BOO FEST, at Zeno Clark’s. Saturday, Halloween Night. After dark. All Speechies welcome.”

“Cool,” I said. “Are you going?”

Vera looked at me with hungry dark eyes. “You know it. I love costume parties! It’ll be right after the Rolling Hills tourney, and everybody’s gonna be there. You just won’t know who’s who.” She broke into a broad grin. “That’s the part I like. Me and Cherise already have our costumes.”

Vera was a compact girl, as short as me but with definition—hips, bust, even her shoulders were more rounded and pronounced, her face contoured under a mellow cocoa complexion. She wore her straightened shoulder-length hair pulled back, or up, or to the side in interesting configurations. But her identifying feature was her posture. She had this

stance,

like a cat ready to spring. I thought I’d probably be able to spot her in any guise.

“What are you going as?”

“That’s for me to know, and you not to find out.”

“We’ll see,” I said.

Miss Sippy and I performed our speeches for each other and then made comments about what was funny and what wasn’t, where things could be speeded up or slowed down, and how the performance might look from a judge’s point of view. Then we got down to the good stuff.

“Who do you think has the best O.C. so far?”

Vera thought. “There’s two or three that are gonna give everybody trouble.”

“Dr. Speak Easy?”

“He’s good, but not that good. Nah, there’s a girl, she’s from that school where they all carry those water bottles around?”

“Evian High!” I said. “I think I saw her.”

“She does an absolute, dead-ringer impression of those dumb-blonde infomercial chicks. No offense,” Vera added.

I shrugged.

“And then there’s a guy, he’s

so

annoying, who does this rap about dating the ugliest girl in school. ‘Mary Ann Pimpleberry,’ he calls it. His name was Guy something. He did the same O.C. last year, so he’s really got it down. But that seems like cheating.”

“And who’s the third contender?”

Vera shot me a look. “Me, girl! You better watch out!”

Touché.

I smiled. “You’ve got my vote,” I said.

Vera turned serious. “Don’t worry about me, Vi. You just go in there and kick some serious Rolling Hills butt, okay?”

“Promise,” I agreed, and we gave each other a closedfist handshake. “You too.”

Afterward, a few of us hung around the front hallway waiting for rides. As I mindlessly ran through my new lines, Clarence said, “Hey, Violet. Do your O.C. for us, will you?”

“Yeah,” said Leda. “We’ll critique it.”

“No,” countered Clarence. “Just for fun.”

So I did.

I couldn’t have asked for a more suck-up audience. Besides them all being on my team, they were slaphappy from several hours of extracurricular concentration. Everybody laughed.

On our way outside, Clarence fell in step with me.

“That was really something, Violet. You’re so creative! Did you just make all that up?”

I shook my head. “Most of it really happened. Sort of.”

“You mean, your family is like that?”

“Pretty much.”

“Sounds like fun.”

“Living with them? It’s—a challenge.”

“I’d like to meet them sometime,” he said sincerely.

“What?” My stomach squirmed. I dropped my folder, and a bunch of English handouts fell to the damp ground, soaking up old rain like dishrags. They tore as Clarence and I picked them up.

I stood there with the ripped, wet papers in my hands as Clarence leapt to his feet.

“Well, bye. I gotta go!” He ran for a car at the curb.

I opened my mouth, but no sound came out. I watched him go. Then I went to catch a ride home with Leda.

The week crawled by. Wednesday, after my piano lesson, I took Chucho for his walk and read a little bit of the Jean Ferris novel I’d checked out of the school library. I was thinking of maybe getting around to doing my Spanish homework when Dad stuck his head in my room and called me to the phone. He was working the graveyard shift at the pharmacy that month and was just waking up. He had on a faded striped pajama top and green paisley bottoms, plus a pair of Mom’s slippers decorated to look like duck feet.

“

Buenos

días,

Dad,” I said to him with a straight face, and dashed downstairs to the kitchen phone.

“Hello?”

“Violet.” The voice poured like liquid velvet from the receiver. No, it sounded more like—what was a strong wood? Oak? Like velvet oak.

“Violet,” it repeated. Whose voice was it?

“It’s Clarence.”

“Oh, yeah, sure. Hi,” I said. His voice sounded—richer over the phone.

Uncomfortable Pause Number One.

“Um, how did you get my number?” I demanded, combing my brain for any discussion topic and coming up with a winner.

“There’s this invention called a phone book,” he said, and I could hear the soft smile in his voice, picture those smooth lips slightly parted in an intimate grin.

The language generator in my brain shut down.

“Is it okay to call you there?” he asked politely when I didn’t answer. “Violet?”

Form. Words. “Oh, sure! Not a problem,” I managed.

Another uncomfortable pause. And we’re both speechies! If it was this hard for us to converse, other people must just grunt and bang the receiver on their heads.

I made a colossal effort to mold a conversation out of these words and silences. “So, Clarence.” That was a start. “Are you ready for the Rolling Hills tourney?”

“I’m always ready,” he said with customary assurance. His game face, he called it. “But that’s not why I’m calling.”

“What’s up?”

“I was wondering if you’re going to Zeno’s party on Saturday.”

“The Halloween party?”

“Yeah, the Clarks throw one every year. Zeno’s older brother was an Extemp champ, Sully Clark. He’s off at Dartmouth. But my brothers always go if they’re in town.”

“So, are

you

going?” Another stellar question.

“I am. And you?”

Now we were getting somewhere. “I—yeah, sure, I’m going,” I said, deciding it then and there.

“I guess I’ll see you at the party then. Just thought I’d ask, since we won’t get a chance to see each other much at the tourney, and I hardly ever run into you in the halls. So . . . I’ll talk to you later.”

“Wait! What’ll you be wearing?”

I heard his easy chuckle. “It’ll be a surprise.”

I hung up, wondering, Did he just ask me on a date? But no, it couldn’t be a date. He didn’t invite me; we were only meeting there. And we might not even be able to recognize each other. I may not have been a social whirlwind, but I knew that even blind dates finally actually

meet

. Was there another type of date, even further removed than a blind date?

Halloween. It would have to be a headless date.