Cyclopedia (15 page)

Authors: William Fotheringham

DESGRANGE, Henri

(b. France, 1865, d. 1940)

Â

The father of two of the sport's premier events: the TOUR DE FRANCE and the HOUR RECORD, and also a founder of the leisure cyclists' AUDAX movement.

An austere figure who began working life as a lawyer's clerk but was caught up in the 1890s passion for cycling, Desgrange lost his job for riding barelegged. He turned to recordbreaking, setting the first hour record at the Buffalo velodrome (see TRACK RACING) in Paris on May 11, 1893, and new standards at distances from 1 kilometer to 100 miles. He then became manager of the Parc des Princes velodrome and later the track that was known as the VELODROME D'HIVER. In 1900, Desgrange was appointed editor of the fledgling newspaper

L'Auto

, but he did not manage to break the market stranglehold of its rival,

Le Vélo

. In December 1902 at a crisis meeting to devise ways to give the paper new impetus, he took up the suggestion of his assistant Géo Lefèvre, a writer on rugby and cycling, for a novel publicity stunt: a bike race longer than any other run before, along the lines of

Le Vélo

's PARISâBRESTâPARIS but that circumnavigated France in five stages. The initial plan was for a race that would take 35 days, but after protests from the professional cyclists who would make up the field this was amended to a six-stage event taking 19 days.

L'Auto

, but he did not manage to break the market stranglehold of its rival,

Le Vélo

. In December 1902 at a crisis meeting to devise ways to give the paper new impetus, he took up the suggestion of his assistant Géo Lefèvre, a writer on rugby and cycling, for a novel publicity stunt: a bike race longer than any other run before, along the lines of

Le Vélo

's PARISâBRESTâPARIS but that circumnavigated France in five stages. The initial plan was for a race that would take 35 days, but after protests from the professional cyclists who would make up the field this was amended to a six-stage event taking 19 days.

The race was announced in the paper on January 19, 1903. Desgrange was not confident of its success and stayed away from the first Tour when it began on July 1, 1903 at the Réveil-Matin Café in the Paris suburb of Montgeron (the centenary Tour of 2003 also began from the Réveil-Matin, still in situ but by then a Wild-West themed restaurant). It was Lefèvre who followed the race from start to finish, traveling by train and bike and providing a page of reports every day. His son described his role like this: “lost all alone in the night, he

would stand on the edge of the road, a storm lantern in his hand, searching the shadows for riders who surged out of the dark from time to time, yelled their name and disappeared into the distance. He alone was the âorganisation' of the Tour de France.”

would stand on the edge of the road, a storm lantern in his hand, searching the shadows for riders who surged out of the dark from time to time, yelled their name and disappeared into the distance. He alone was the âorganisation' of the Tour de France.”

The first Tour was an unqualified success:

L'Auto

's circulation jumped from 25,000 to 65,000, and

Le Vélo

went bust. By the second running of the Tour, however, the field had worked out ways of getting around the rudimentary rules and there was a wave of cheating, which led Desgrange to announce that “The Tour de France is finished.” But in 1905 he personally took over the running of the race and brought in numerous changes, most importantly shorter stages that meant the riders would not be out on lonely French country roads at night.

L'Auto

's circulation jumped from 25,000 to 65,000, and

Le Vélo

went bust. By the second running of the Tour, however, the field had worked out ways of getting around the rudimentary rules and there was a wave of cheating, which led Desgrange to announce that “The Tour de France is finished.” But in 1905 he personally took over the running of the race and brought in numerous changes, most importantly shorter stages that meant the riders would not be out on lonely French country roads at night.

Under Desgrange, the Tour was run dictatorially but also with a constant search for novelty and timeliness, which remains part of the organizers' ethos today. It was, wrote Geoffrey Nicholson, “established as a battle against fearful odds often fought in inhospitable regions which the readers of newspaper reports could only imagine.” He took the event into the disputed territory of Alsace-Lorraine in 1906, ran the first mountain stages, experimented with team time trials and attempted to limit the influence of the cycle manufacturers by making the riders use identical machines issued by the race organizers. He also brought in the advance caravan of advertising vehicles that draws spectators today.

A believer that exercise and suffering led to moral improvement, he was uncompromising in his merciless attitude to the riders, giving rise to some of the Tour's most legendary episodes (see HEROIC ERA; PELISSIER for examples). During the First World War, Desgrange enrolled as an infantryman and won the Croix de Guerre; he returned

to his paper in 1919 when he conceived his masterstroke: the introduction of a distinctive jersey as a way of recognizing the race leader. The jersey was yellow, the same color as the pages of

L'Auto

; the jersey bears his initials even today, and every stage race in the world has a leader's jersey, usually yellow.

to his paper in 1919 when he conceived his masterstroke: the introduction of a distinctive jersey as a way of recognizing the race leader. The jersey was yellow, the same color as the pages of

L'Auto

; the jersey bears his initials even today, and every stage race in the world has a leader's jersey, usually yellow.

Desgrange began the tradition that the Tour organizer should also be a journalist. As a writer, he modeled himself on Ãmile Zola. His style was florid and crammed with imagery and is still imitated by color-writers on

L 'Auto

's successor

L'Equipe

today. His essay in

L'Auto

introducing the Tour was entitled “The Sowers” and begins: “With the broad and powerful swing of the hand which Zola gave to his ploughman in

The Earth

,

L' Auto

, a paper of ideas and action, is going to fling across France today those reckless and uncouth sowers of energy, the great professional road racers.... From Paris to the blue waves of the Mediterranean, along the rosy, dreaming roads sleeping under the sun, across the calm of the fields of the Vendée, following the still and silently flowing Loire, our men are going to race madly and tirelessly.” He described Henri Pelissier's win in 1923 as having “the classicism of a work by Racine, the value of a perfect statue, a faultless classic or a piece of music destined to stay in everyone's minds.”

L 'Auto

's successor

L'Equipe

today. His essay in

L'Auto

introducing the Tour was entitled “The Sowers” and begins: “With the broad and powerful swing of the hand which Zola gave to his ploughman in

The Earth

,

L' Auto

, a paper of ideas and action, is going to fling across France today those reckless and uncouth sowers of energy, the great professional road racers.... From Paris to the blue waves of the Mediterranean, along the rosy, dreaming roads sleeping under the sun, across the calm of the fields of the Vendée, following the still and silently flowing Loire, our men are going to race madly and tirelessly.” He described Henri Pelissier's win in 1923 as having “the classicism of a work by Racine, the value of a perfect statue, a faultless classic or a piece of music destined to stay in everyone's minds.”

Desgrange cohabited for much of his life with the avant-garde artist Jeanne (Jane) Deley. In 1936, after a prostate operation, he gave up the running of the Tour de France to Jacques Goddetâthe son of the

L'Auto

treasurer Victor Goddetâand after he died in 1940 a MEMORIAL was put up in his honor on top of the Col du Galibier. A street off Quai de Bercy next to the Seine, on the southeast side of Paris (post code 75012) is named after him.

L'Auto

treasurer Victor Goddetâand after he died in 1940 a MEMORIAL was put up in his honor on top of the Col du Galibier. A street off Quai de Bercy next to the Seine, on the southeast side of Paris (post code 75012) is named after him.

DOGS

Man's best friend, a cyclist's worst enemy* (and occasional training aid as you sprint to get away from those snapping teeth). Victorian cyclists carried heavyweight small-caliber pistols to deal with threatening muttsâpresumably on a high-wheel Old Ordinary there was a serious risk of losing control during a dog attack. The Germans made gunpowder-filled anti-dog grenades, while US cyclists could buy ammonia sprays and some still carry mace or pepper spray. One US study estimated that 8 percent of cycle accidents were caused by Fido and friends.

Man's best friend, a cyclist's worst enemy* (and occasional training aid as you sprint to get away from those snapping teeth). Victorian cyclists carried heavyweight small-caliber pistols to deal with threatening muttsâpresumably on a high-wheel Old Ordinary there was a serious risk of losing control during a dog attack. The Germans made gunpowder-filled anti-dog grenades, while US cyclists could buy ammonia sprays and some still carry mace or pepper spray. One US study estimated that 8 percent of cycle accidents were caused by Fido and friends.

While matches between cyclists and HORSES go back over a century, races between cyclists and canines are more recent. In 2009, the Spanish champion Alejandro Valverde lost a circuit race in Valencia against a team of six huskies drawing a wheeled sleigh. A rematch was called for, with two cyclists taking on the huskies, but halfway through the animals decided it was time for a nap.

Dogs sometimes intervene in major bike races, for example in two stages in the 2007 TOUR DE FRANCE, where pooch-bike interface resulted in injuries to, firstly, the German Marcus Burghardt, and, later, Frenchman Sandy Casar, who won a stage after being brought down by a dog early on.

The best-known dog in pro racing belongs to the 2009 world champion Cadel Evans of Australia. In a media crush at the 2008 Tour, Evans shouted at one journalist, “If you stand on my dog I'll cut your head off.” His website later sold T-shirts with the motto: “Don't stand on my dog.”

In the 1950s, the cycling cartoonist Johnny Helms perfectly depicted the cyclist's nightmare: a mischievous

breed of hound with sharklike teeth and gaping grin, often with a scrap of cycling shorts in its mouth. The bestselling bike bible

Richard's Bicycle Book

by RICHARD BALLANTINE offers a grimly detailed guide on dealing with vicious dogs. He recommends using pepper sprays, ramming the pump down the dog's throat, kicking its genitals. He concludes: “If worst comes to worst and you are forced down to the ground by a dog, ram your entire arm down his throat. He will choke and die. Better your arm than your throat.”

breed of hound with sharklike teeth and gaping grin, often with a scrap of cycling shorts in its mouth. The bestselling bike bible

Richard's Bicycle Book

by RICHARD BALLANTINE offers a grimly detailed guide on dealing with vicious dogs. He recommends using pepper sprays, ramming the pump down the dog's throat, kicking its genitals. He concludes: “If worst comes to worst and you are forced down to the ground by a dog, ram your entire arm down his throat. He will choke and die. Better your arm than your throat.”

* THIS IS TAKING “ENEMY” AS REFERRING TO AN ANIMATE ENTITY; THE GREATEST DANGER, OBVIOUSLY, COMES FROM INANIMATE OBJECTS WITH FOUR WHEELS OR MORE AND AN ENGINE.

DOLOMITES

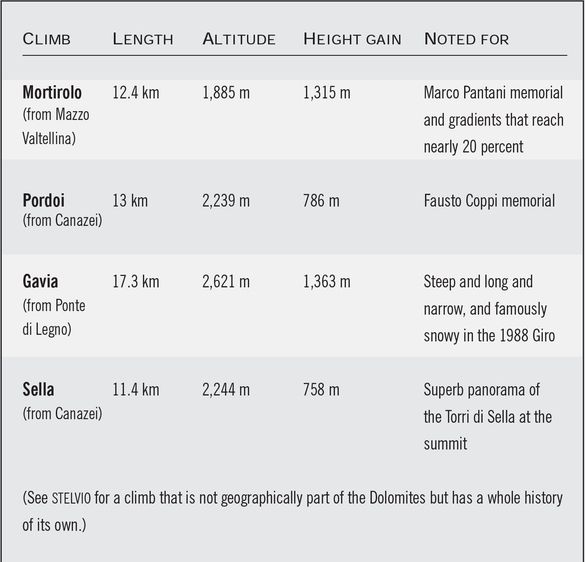

It was not until the 1930s that the GIRO D'ITALIA visited the passes through the section of the ALPS that dominates northern Italy. However, they are now decisive in the race, which also uses the climbs of the southeastern Alps and the shorter, less testing ascents in the Apennines. Geographically, Dolomites refers to the mountains between the Adige river in the west and the Piave valley to the east. Dolomite climbs frequently have spectacular backdrops such as the rock pinnacles on the Pordoi pass. They are shorter and steeper than the Alpine climbs that figure in the TOUR DE FRANCE.

It was not until the 1930s that the GIRO D'ITALIA visited the passes through the section of the ALPS that dominates northern Italy. However, they are now decisive in the race, which also uses the climbs of the southeastern Alps and the shorter, less testing ascents in the Apennines. Geographically, Dolomites refers to the mountains between the Adige river in the west and the Piave valley to the east. Dolomite climbs frequently have spectacular backdrops such as the rock pinnacles on the Pordoi pass. They are shorter and steeper than the Alpine climbs that figure in the TOUR DE FRANCE.

The Giro tackles the Dolomites in early summer and is vulnerable to extreme weather. The most legendary example was in 1988 on the Gavia Pass, which lies in the west of the range between Sondrio and Brescia. This was the springboard for the first win in the Giro for the UNITED STATES as Andy Hampsten took over the pink leader's jersey on a notorious day when heavy snow fell unexpectedly on this high pass

with its unmetaled roads. There were dramatic scenes as shivering riders stopped on the descent to urinate on their frozen hands.

with its unmetaled roads. There were dramatic scenes as shivering riders stopped on the descent to urinate on their frozen hands.

The most notorious Dolomite passes are shown below.

Numerous CYCLOSPORTIVES take in the great passes of the Dolomites, most notably the

Maratona dles Dolomites

, founded in 1987 and now so popular that 5,000 of the 9,000 places are designated by a lottery; the event draws around 20,000 applications. The event is subdivided into three courses of varying severity, all starting and finishing in the town of Corvara in the Badia valley: the toughest, over 86 miles, includes the climbs of Campolongo (twice), Pordoi, Sella, Gardena, Giau, and Falzarego. None of the passes is over seven miles long but their steepness means the total amount of climbing is 13,747 feet.

Maratona dles Dolomites

, founded in 1987 and now so popular that 5,000 of the 9,000 places are designated by a lottery; the event draws around 20,000 applications. The event is subdivided into three courses of varying severity, all starting and finishing in the town of Corvara in the Badia valley: the toughest, over 86 miles, includes the climbs of Campolongo (twice), Pordoi, Sella, Gardena, Giau, and Falzarego. None of the passes is over seven miles long but their steepness means the total amount of climbing is 13,747 feet.

The Granfondo Sportful

, (previously known as GF Campagnolo, but now with new sponsor) is held on the third Sunday in June, based in the town of Feltre, and covers six Dolomite passes, including the Croce d'Aune (see CAMPAGNOLO for the significance of this climb in cycling history).

, (previously known as GF Campagnolo, but now with new sponsor) is held on the third Sunday in June, based in the town of Feltre, and covers six Dolomite passes, including the Croce d'Aune (see CAMPAGNOLO for the significance of this climb in cycling history).

Other books

Love Inspired January 2016, Box Set 1 of 2 by Carolyne Aarsen

Steven Gerrard: My Liverpool Story by Gerrard, Steven

Tiger Bound by Doranna Durgin

Breath, Eyes, Memory by Edwidge Danticat

Son of Hamas by Mosab Hassan Yousef, Mosab Hassan Yousef

The Texas Ranger's Family by Rebecca Winters

The Book of Souls (The Inspector McLean Mysteries) by Oswald, James

Correction: A Novel by Thomas Bernhard

Lost Among the Stars (Sky Riders) by Rebecca Lorino Pond

Sin in the Second City by Karen Abbott