Daily Life During the French Revolution (16 page)

Read Daily Life During the French Revolution Online

Authors: James M. Anderson

Embroidered handkerchiefs and fans continued to be carried,

but, in place of the exquisite and costly works of art in ivory, tortoise

shell, or mother-of-pearl, fans were now made of wood or paper and embellished

with brilliant designs depicting, for instance, the National Guard, Lafayette,

or the Estates-General.

Because they had operated under royal patronage, the lace

factories were torn down and demolished. Some of the lacemakers were put to

death and their patterns destroyed.

The uniform of the sans-culottes did not meet with great

success and lasted only a few years. It was cast aside after the fall of the

Jacobins in July 1794, when the Convention, always looking toward uniformity,

commissioned the artist Jacques-Louis David to create a national costume.

Attempting to fill the requirements of an outfit suitable to the ideal of

equality within the new social order, David produced a design that consisted of

tight trousers with boots, a tunic, and a short coat, but this was never put

into practice.

In 1797, the outcome of the search for a national dress was

that all materials had to be made in France and the principal colors should be

blue, white, and red. Eventually, all deputies were ordered to wear a coat of

blue, a tricolor belt, a scarlet cloak, and a velvet hat with the tricolored

plume.

Before the revolution, children were given traditional

names such as Jacques, René, Antoine, Sophie, and Françoise. Saints’ names,

once so popular and widespread, were now out of favor, so others had to be

found to replace them. Names of heroes of the revolution or taken from the much-admired

Romans and Greeks now began to be used, and names like Brutus and Epaminondas

(a Greek general who defeated the Spartans) were employed. One female infant

was registered as Phytogynéantrope, which means “a woman who gives birth only

to warrior sons.” Other babies were given names containing Marat or August the

Tenth, Fructidor, and even Constitution. One girl was called

Civilization-Jemmapes-République. Her nickname has not been recorded.

The red bonnet has a special place in French history. It

was modeled on the ancient Phrygian cap adopted by freed slaves in Roman times

as a symbol of liberty. Regardless of the material and whether it had a hanging

pointed crown or was simply a skullcap with a pointed crown, it was always

ornamented with the tricolor cockade. By the end of 1792, this cap represented

the political power of the militant sans-culottes and served to identify them

with the lower ranks of the Third Estate of the Old Regime. Although the revolutionary

bourgeoisie rarely wore the red bonnet, many citizens did so spontaneously,

wishing to demonstrate clearly their repudiation of all that had gone before.

These bonnets were held high at ceremonies, sometimes placed on the top of

poles or hung on liberty trees, and vividly symbolized the new freedom from the

old absolute oppression. After the invasion of the Tuileries palace, on June

20, 1792, even the king put on one of these red caps, albeit reluctantly.

All streets and squares in Paris that had been named for

the king, court, or someone who had served the monarchy were changed to honor

the revolution: Place de Louis XV became the Place de la Révolution, rue

Bourbon became rue de Lille, and rue Madame was changed to rue des Citoyennes.

In addition, streets previously named for Saint Denis, Saint Foch, and Saint

Antoine became simply rue Denis, rue Foch, and rue Antoine. The cathedral of

Nôtre Dame became the Temple of Reason. Provincial towns with names of saints

or royalty sometimes changed their name completely; for example,

Saint-Lô

became

known as

Rocher de la Liberté.

To conform to the egalitarian spirit of the times, the

familiar second-person singular,

tu,

was used instead of the formal

vous

throughout much of the country. The idea of using

tu

in all

circumstances was first proposed in an article in the

Mercure National

on

December 14, 1790, but nothing more was said about it until three years later,

when the article came to the attention of the Convention. No laws were passed

registering the mandatory use of

tu,

but the debate stirred the public

and that form of “you” began to spread. Now the baker’s apprentice could

address his master and clients in a familiar form, a practice that had been

strictly forbidden. Within a short time, people in Paris were speaking to one

another as if they were family or long-time, intimate friends. Anyone who

continued to use

vous

was treated as suspect.

Similarly, the forms of address

Monsieur

and

Madam

e

were replaced by

Citoyen

and

Citoyenne

with the same objective of

eliminating class distinction. All over the country, “Citizen” was the only

recognized form of address. Plays already being staged and works in the offing

had to have their wording changed to conform to the new usage. When a player at

the

Opéra-Comique

inadvertently used the old forms in a speech, he was

not excused for a lapse of memory and had to duck out of the way as the seats

were thrown at him.

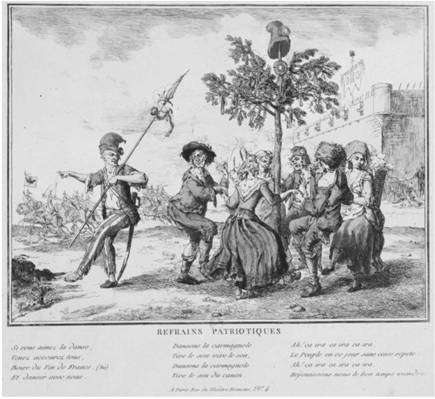

Sans-culottes dancing around a

Liberty Tree decorated with a cockade and the revolutionary red bonnet. The

Bastille is shown on the right, and an Austrian army being routed is seen to

the left.

THE DIRECTORY

With the Directory came new trends based on the classical

styles of ancient Greece and Rome. As fashion journals began to reappear, daily

life returned to the trappings of normality. When

émigrés

returned to

France, they were often seen wearing the blond wigs of the anti-revolutionaries

of the earlier time as well as a black collar as a sign of mourning for the

fate of king, queen, and country and a green cravat signifying royal fidelity. The

revolutionary, on the other hand, wore a red collar on his coat, and the

antagonisms between the blacks and reds led to numerous fierce street battles.

Instead of expensive necklaces and rings, women began

wearing gilded copper wedding rings with the words “Nation,” “Law,” and “King”

engraved on them and earrings made of glass and a variety of other trinkets,

sometimes made out of bits of stone from the Bastille.

After the Terror and during the years of the Directory, the

Muscadins

and the

Merveilleuses

—children of the wealthy

bourgeoisie—reacted against the austerity of the government. To demonstrate

their independence and their repudiation of the republican state, they went to

extremes in the way they dressed, openly showing contempt for what they

considered to be Jacobin mediocrity. Very little attention was paid by this

group to the principles of virtue and morality.

The

Muscadins,

also known as the

Incroyables,

Impossibles,

or

Petits-Maîtres,

were rich and effeminate

middle-class dandies who copied the clothes of the earlier court nobility,

strutting about like peacocks. They were mainly young Parisians who had avoided

conscription in the revolutionary wars.

They were seen in frock coats, sometimes with large pleats

across the back and high, turndown collars and exaggerated lapels that sloped

away from the waist when buttoned. Corsets helped show off small waistlines,

since the coats fitted snugly. An elaborate vest with as many as three visible

layers of different colors on the bottom edge would also have had a high collar

that turned down to show the inside neck of the coat. Coats and vests were

beribboned and had buttonholes of gold. A monocle, a sword, or even a hunting

knife might be worn and a knotted, wooden, lead-weighted stick carried in the

hand.

A large, muslin cravat, often fastened with a jeweled pin,

had a padded silk cushion concealed underneath. It was wound loosely around the

neck several times. Lace filled any remaining opening in the vest. Their

breeches (or culottes), fastened with buttons or ribbons just below the knees,

usually were worn with striped silk stockings and high black boots.

The

Muscadins

’ felt hats were extreme in size and

were decorated with red, white, and blue rosette,, although many appeared in

the white, royalist cockade (in defiance of the law) and sometimes also a silk

cord or a plume. Hoop earrings often dangled from their ears. They were

thoroughly disliked, as their showy dress threatened the sedate and serious

image being cultivated by the bourgeoisie. They were employed by the

Thermidorians to terrorize former radicals but were repressed when their

usefulness came to an end.

Others chose to wear more dignified and refined styles,

including frock coats with small lapels and stand-up collars in black or violet

velvet, black satin vests, and very tight breeches of dull blue cloth. Other

popular colors were canary yellow and bottle green with a brown coat, the latter

with small lapels and a modest standing collar. The silk or muslin cravat came

in green, bright red, or black. Boots of various heights were made of soft

leather and had pointed toes; stockings were generally white or striped. Once

again, two watches or charms hung from the vest, and the lorgnette was used.

Hair was beginning to be cut short in the Roman style.

After the Terror, people began to enjoy themselves again.

One of the best-known of the open-air dance pavilions was the

Bal des

Victimes,

so-called because only those who had lost a relative to the

guillotine could go there. Men who attended the dance pavilions generally kept

their hair short, often in a ragged cut.

The

Merveilleuses,

the female counterpart of the

Muscadins,

were often seen in gowns cut in the classical Greek tradition. In Paris,

some of these women began to wear see-through or even topless diaphanous gowns

or a transparent tunic over flesh-colored silk tights. The predominant color

was white; this remained so throughout the period of the Empire. Necklines were

very low, bodices short and tight, and skirts full and with trains that were

carried over the arm. In addition, knee-length tunics were popular, split up

the sides, sometimes as far as the waist, to show a bare leg or flesh-colored

tights.

Some gowns were sleeveless, the material held together with

brooches at the shoulders, long gloves covering the bare arms. If there were

sleeves, they were either long and tight or very short. Materials were sheer

Indian muslin, sometimes embroidered, gauze, lace, or very light cotton. There

were no pockets in the gowns, so small drawstring embroidered bags, often with

fringes and tassels, were suspended from the belt to hold necessary articles.

Outdoors, long, narrow scarves of cashmere, serge, silk, or

rabbit wool in colors such as orange, white, and black were worn over the light

gowns. The scarves matched the wearers’ bonnets. High-crowned straw bonnets

were trimmed with lace, ribbons, feathers, or flowers. The meaning of the word

“bonnet” (previously applied to men’s toques) had changed by this time to

designate a woman’s hat that was tied under the chin. Other hats included

turbans.

Blond wigs and switches of false hair again made their

appearance. It was usual to change wigs frequently, and many women owned 10 or

more. Wigs were curled and decorated with ribbons or jewels. Ancient hairstyles

were copied, and in hairdressing salons, busts of goddesses and empresses were

exhibited. When a woman chose not to wear a wig, her hair was plaited or curled

in the manner of the ancients, brushed back, waved, curled, oiled, and knotted

or twisted at the nape of the neck in a psyche knot. Some women cut their hair

short, brushed it in all directions from the crown, with uneven ends hanging

over the forehead and sides, occasionally with long, straggling pieces hanging

down at the sides of the face, and shaved the back of their heads to create a

style known as

coiffure à la Titus.

A short-lived fad was to appear with

shaved heads and a ribbon of red velvet around the throat, a gruesome reminder

of the victims of the guillotine.

Jewelry, such as necklaces, rings, and bracelets for bare

ankles and toes, was extensively worn, along with strings of pearls in the hair

and jeweled belts about two inches wide worn just under the breasts.

Apple green remained a favorite color, and the soft, flat,

pointed sandals—sometimes just a sole strapped to the foot by ribbons—were

often of this shade. The sandals could be laced up to and around the ankle with

narrow, red straps decorated with jewels—but more often flat slippers of fabric

or kid were worn with white silk stockings. A small bow or edging finished the

slipper.