Daily Life During The Reformation (33 page)

Read Daily Life During The Reformation Online

Authors: James M. Anderson

TOBACCO

Tobacco was thought to have many medicinal uses; smoking

was supposed to prevent catarrh, alleviate fatigue, be a gentle laxative, and

to fortify the stomach. Application of the green leaves to the skin was

supposed to cure leprosy, kill lice, and heal wounds. Tobacco juice was also

used to make a dressing for cuts, bruises and burns, gunshot wounds, and to

cure the bites of venomous creatures when mixed with olive oil, turpentine,

wax, and verdigris. For colic, rectal injections of tobacco smoke were

employed.

RURAL MEDICINE

People in villages and small towns continued to visit local

men and women who practiced medical skills and cures handed down by example and

word of mouth through the ages. There was generally someone, even in a hamlet,

that had some knowledge of the benefits of herbs and spices that figured

largely into their remedies. Some ingredients could be obtained locally; others

were imported. In cities, apothecaries often blended plants for the desired

medicine that might consist of pepper, cloves, ginger, and China root, the

latter for gout. Imported ingredients could be expensive and unavailable to the

poor. For injuries such as a broken leg or arm the local blacksmith or barber

was called upon to set the injured limb.

BLEEDING

For rich and poor alike, bleeding was done to help rid a

patient of evil fluids in which disease flourished. Those who could afford the

process, sometimes had themselves bled four times a year. Others, much more. A

bleeding holiday was not unusual in which families and friends went in groups

to the public baths where surgeons opened their veins and allowed the blood to

flow. Taken from the elbow, chest, or from the basilic or temporal vein, it was

the most common treatment for releasing toxic humors. Every sickness had its

own specific vein. Letting of blood was thus used as a panacea since most

illnesses were thought to be the result of unclean substances in the body, the

bleeding casting them out to restore the natural equilibrium.

THERMAL WATERS

Others had great faith in the benefits of the waters of

thermal springs to be drunk at the source if possible. There, the patient would

be purged and then combine rest with bathing and drinking some two to three

liters of water daily.

HOSPITALS

Not many people went into hospitals, which were considered

mostly as places for the homeless and somewhere to die. Care was far from

adequate and sometimes as many as six people with a variety of illnesses, were

put in the same bed, which was seldom clean. In the sixteenth century, there

were five epidemics of the plague, and those who contracted it were not

admitted to hospital in England, for example, unless there were special houses

to confine them. Hospitals, themselves, usually financed by a charitable patron

or the town hall, were places where disease spread easily.

THE CATHOLIC CHURCH

Many doctors thought they would have more chance of success

in curing the patient if they prayed before administering their treatment. The

Catholic Church in Europe continued to promote Galen’s anatomical ideas as

infallible, and its control over medical practice and training in the

universities remained strong. However, as the Renaissance took hold in Europe,

and inventions such as the microscope appeared, leading doctors began more and

more to investigate the anatomy and physiology of the body. Classical theories

were put to the test of thorough investigation for the first time. The ideas of

Galen were hard to overturn, however, since his theories had been the accepted

wisdom of the medical world for more than a thousand years. Even when he

appeared to be wrong, many doctors would doubt or ignore their own observations

and adhere to the time honored views.

A scholar who questioned old ideas, such as those of Galen

on the human body, went against the commonly accepted views and would acquire

many enemies. Nevertheless, there were a few men who found new paths forward in

the fields of medicine and science. Change was slow in the use of new drugs

such as the chemicals (e.g., mercury, antimony, and quinine) in the treatment

of disease.

DISSECTION

In the sixteenth century, dissection of the human body

became more common. Previously, the only dissections that had been permissible

were those undertaken on the corpses of criminals, and these had been carried

out purely to support Galen’s theories. By the sixteenth century, the main

pressure to maintain the general ban on dissection came from senior university

professors, who were afraid that the ideas of Galen (who experimented only on

animals) would be challenged by new discoveries. Andreas Vesalius, who distrusted

the teachings of Galen, made his own observations when he became professor of

surgery at the University of Padua in 1537. He taught his students using the

dissection of human corpses to illustrate anatomical facts. The tradition that

dissection should only be done while a professor read aloud the theories of

Galen was dropped. In the pioneering atmosphere of the Renaissance, dissection

was accepted as a means to develop new ideas and explain these to students.

GERMANY

To combat diseases in Germany, people followed the oral

traditions including a purging calendar (published in Nurnberg, 1496).

Physicians tended to think of medicine and their services as divinely inspired.

For all but a few, faith and prayers were the most important remedies for ill health;

but when all else failed, God allowed one more possibility, consult the doctor.

Many physicians, devout as any clergyman, considered plague to be God’s curse

on the wicked.

Physicians also gave sensible advice in many cases,

alerting people to the fact that disease was spread by physical contact and

cautioned people to avoid the afflicted, their houses, clothes, bed covers, and

so on. Ventilation was important in closed spaces, alcohol should be avoided, a

clean house maintained; one should eat lightly, bathe frequently, and stay warm

in winter with a continuous fire in the hearth. Like most people, they believed

in talismans such as sapphires to be worn in the streets to ward off disease.

The English traveler, Fynes Moryson, having fallen ill in

Leipzig, recounts that German physicians were very honest and learned. They

never took money until the cure was complete; and if the patient died, they

expected no pay. Apothecaries were few in the city; only those permitted by the

prince could practice. They sold drugs at a reasonable rate, and were careful

not to sell spoiled medicines. To prevent any fraud, imperial laws and local

decrees demanded that once a year physicians visit the apothecary shops and

destroy all out of date drugs no longer fit to be used.

QUACKS

Throughout Europe, medicine men roamed the countryside

stopping at hamlets, farms, and local markets to peddle their elixir promising

it as a panacea for just about everything.

Moryson noted that in Germany as in Italy, there were

quacks who professed to have special salves, oils for most ailments, and who

carried testimonials under seals of princes and free cities that attested to

the cures they had performed. These were mounted on walls and stalls in the

market place where they lectured on their skills in applying them. They pictured

drawings of cures, gall stones they had removed from patients, and teeth they

had extracted.

FRANCE

In sixteenth-century France, Montpellier’s School of

Medicine was internationally famous and highly respected. It was here that

Felix Platter, at age 15, was sent from his home in Basel to study. Felix was a

Protestant; and Montpellier, although known as a haven for Protestants, still

witnessed some violence and persecution as he noted when Bibles found in a

bookshop were publicly burned. German-speaking Protestant students generally

stuck together, as did the French-speaking Catholic students.

He attended four to six lectures daily. The first autopsy

he saw was on the body of a boy whose death derived from a stomach absess. A

professor presided, and the surgery was done by a barber-surgeon. A large,

attentive audience witnessed the event including some monks. At the conclusion

of his studies, Felix returned to Basel to become the foremost physician in that

town.

ENGLAND

The state of medicine and the diseases doctors endeavored

to manage or cure were no different than those on the European continent. There

as elsewhere, the major cause of disease was the absence of sanitation. London

and other cities had open sewers in the streets that also served as garbage

dumps, and animals and sometimes people defecated wherever they pleased.

Typhoid was spread from contaminated shared wells. As elsewhere in Europe, the

vast majority of people could not afford good doctors who, at any rate, would

not attend patients with plague, typhoid fever, and other highly contagious

diseases. Housewives kept on hand certain herbs and potions for family use that

were often the only remedies for illness among the poor. Not only were sewers

unhealthy places, but rivers and streams were often blocked by rotting garbage

and attracted multitudes of rats and mice. Again, as elsewhere, every

household, rich and poor, had its share of lice and fleas.

BARBER SURGEONS

Most barbers filled other functions besides cutting hair

and shaving beards. They also pulled teeth and performed surgical procedures,

occasionally including amputations. They treated trauma, set broken bones,

cauterized (sometimes with the use of a red-hot iron) or stitched up bleeding

wounds, and bled patients. If their services were not required by humans, they

often took care of sick animals.

Wounds were cleaned and washed with salted water as a first

aid measure. Splinting and traction were employed in the treatment of fractures.

In injuries of the mouth, which rendered the intake of food difficult or

impossible, nourishment was administered by means of nutrient enemas.

Barber surgeons were not doctors and needed only on-the-job

training, not a university degree. They were looked down upon by physicians

whose education was better and whose services were much more expensive.

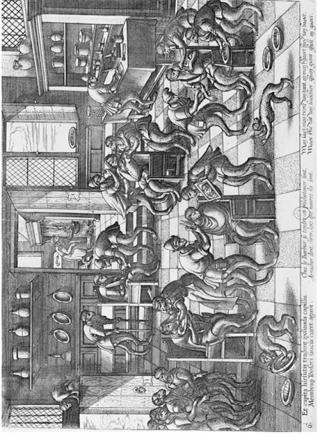

Paoli Magni. At the Barber

Surgeon’s. 1854. A satirical engraving illustrating the many tasks performed by

barber surgeons. One could have wounds treated, blood let, teeth pulled, and

hair cut.

ANESTHESIA

Anesthesia was primitive and often not used at all. When

amputations or other procedures were performed, a patient’s hands and feet were

tied to the table, and various methods were tried to render him unconscious

including putting a helmet on him and delivering a solid blow to it with a

wooden hammer. Another procedure used sponges soaked in mandrake and belladonna

pressed against the mouth. In both cases, the odds of killing the patient,

instead of merely rendering him unconscious, were high. Shock and infection

frequently killed most of those who survived the surgery anyway.

DENTISTRY

In England, tooth decay was rampant among the upper classes

who consumed huge quantities of sugar, used in almost every dish—sweet or

savory. A large number of people, including the queen, had black teeth in a

seriously bad state of deterioration.

To combat this, many would dip their fingers into powdered

alabaster or ashes of rosemary leaves, which they rubbed onto the teeth. Other

methods included rinsing them with a solution of honey and burnt salt or with a

quart of vinegar and honey and half a quart of white wine boiled together.

Sometimes the teeth were rubbed with a mixture made of powdered pumice stone, brick,

or coral. This frequently removed stain, along with the enamel.