Daily Life In The Ottoman Empire (15 page)

Read Daily Life In The Ottoman Empire Online

Authors: Mehrdad Kia

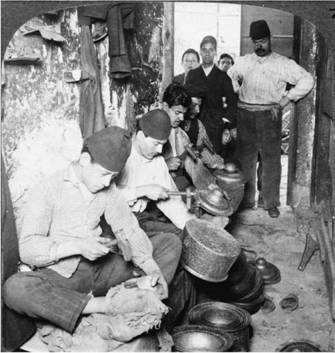

Boutique et marchand turcs

(c. 1880–1890). Merchants with

an outside shop in Istanbul. Sebah and Joaillier.

GUILDS

In the Ottoman Empire, the craftsmen were organized into

guilds. The manufacturers, shopkeepers, and small traders who were organized

under the guild system were known as

esnaf

(plural of

sinf)

.

Trade guilds already existed in Constantinople at the time of the Ottoman

conquest in 1453. The number of guilds increased significantly as the city was

rebuilt and repopulated under Mehmed II and his successors. In the 17th

century, the Ottoman writer Evliya Çelebi listed over one thousand guilds in

the capital. He also wrote that there were nearly eighty thousand craftsmen in

Istanbul alone, “working in more than 23,000 shops and workshops, and divided

up into 1,100 different professional groups.” Three centuries later, a foreign

observer estimated the number of distinct trades and crafts in Istanbul at one

thousand six hundred and forty.

Guilds were organized principally to manufacture consumer

goods in demand by the population, regulate prices and competition, and

facilitate the relationship between various trades and the government.

Additionally, guilds provided assistance “to craftsmen to open shops, gave

money to the sick, and took on the costs of burial if a member died.” They also

“paid the wage of guards and firemen, gave alms to beggars in the bazaars, and

made sure that the master craftsmen gave proper training to their apprentices,

for only by qualifying as masters could the latter open a workshop of their

own.”

The Ottoman central government frequently intervened in the

daily affairs of the guilds. The state “dominated both production and

distribution, determining even the range of profits permitted to a craftsman.” With

participation and support of guild masters, Ottoman state officials fixed the

number of guilds in every city and disallowed the establishment of new shops

and workplaces. The guilds were not organized to produce for “a continuously

expanding market,” and they could not enrich themselves at the expense of the

consumer. They manufactured primarily for the population of their city and its

neighboring towns and villages, and every effort was made by state officials to

protect “both the consumer and the producer” by keeping “the consumption and

production balanced.”

Given “the weakness of the urban police force,” the Ottoman

central government also “used the guilds as a means of controlling the urban

population.” In addition, the guilds procured services needed by the army and

navy, and secured payment of taxes and dues. A significant number of craftsmen

were drafted into military campaigns. This was done because “to supply the

soldiers with boots, coats and tents; the necessary investments had to be made

by the relevant guilds.” Some guilds, such as those of rowers, oarsmen,

waterfront workers, and boatmen who “linked Uskudar, Galata, and the Bosphorus

villages to Istanbul,” were recruited by the Ottoman navy to work at the

dockyards.

The daily activities of urban guilds were inextricably

linked to the surrounding villages and rural communities, which supplied the

craftsmen with such raw materials as wool, hides, cotton, grain, and other

goods. At times, the urban manufacturers purchased these basic materials from

peasant farmers. In return, on rare occasions, peasants from nearby villages

came to the town’s craftsmen to purchase the textiles they used for new clothes

at weddings and other important ceremonies. These direct commercial exchanges

between the urban guilds and rural communities were rare, however, because

peasants “produced most of the goods they needed at home, while many artisans

bought through their guilds and/or from tax-farmers, and thus did not do their

purchasing directly from villages.” In the majority of cases, peasants did not

earn sufficient cash to buy finished goods from urban craftsmen. The little

cash they earned was paid as tax to government officials. The artisans, on the

other hand, did not produce to serve the needs of peasant farmers. Their

principal customers were the members of the ruling elite, the merchants, and

other craftsmen.

Each guild “had a fixed number of members, and if one died,

his place went to his son, or a travelling trader would buy the tools and wares

of the deceased, and the money would go to his family.” Every guild was

distinguished by its own internal structure, code of conduct, and attire. Ottoman

guilds were inherently hierarchical, and each possessed its own organization.

Customarily, however, its members were divided into the three grades of

masters, journeymen, and apprentices. A very old and well-established conduct

code obligated the journeymen to treat their masters with utmost respect and

obedience, while the apprentices were expected to display reverence and

deference to both the journeymen and masters. Within the guild hierarchy, the

apprentices constituted the lowest category. Each apprentice had two comrades;

one master teacher; and one

pir,

or the leader of his order. The

apprentice learned his craft and trade under the close supervision of a master.

Members of each guild also met at

derviş

lodges where the masters

of the trade taught the apprentices the ethical values and standards of the

organization. After several years of hard work, when it was decided that the

apprentice was qualified in his craft, a public ceremony was organized where he

received an apron from his master. The apron-passing ceremony involved

festivities and performances: orators recited poems, singers sang, and dancers

danced, while jugglers, rope-dancers, sword swallowers, conjurers, and acrobats

performed and showed off their skills.

The

kethüda,

or the senior officer and spokesperson

of the guild, collected taxes for the state and represented his craft in all

dealings and negotiations with the central government. Moreover, each guild had

a

şeyh

who acted as the spiritual and religious head of the craft

guild. Among Ottoman guilds, competition and profiteering were viewed as

dishonorable. Those who attracted customers by praising and promoting their

products, and worked primarily to accumulate money, were expelled from the

guild. The craftsman was respected for the beauty and artistic quality of his

work and not his ability to market his products and maximize his profit. Not

surprisingly, traders did not display signs and advertisements to draw the

attention of buyers to their business. They merely displayed the pieces and

products, which the buyer requested, and did not bargain over the price.

An important characteristic of the Ottoman guild system was

the highly specialized nature of every branch of craft and industry. There were

no shops that sold a variety of goods. If one needed to purchase a pair of

shoes, he would go to the shoemaker section of the bazaar, and if his wife

needed a new saucepan, kettle, or coffeepot, she sent her husband or servant to

the street where the coppersmiths were located.

Metal workers in a factory in

Izmir.

IHTISAB AND MUHTASIB

All Ottoman guilds abided by the traditional rules, which

had been set down in the manuals of the semireligious fraternities (

futuwwa)

,

guild certificates, and various imperial edicts (

fermans

). Specific laws

and regulations (

ihtisab)

governed public morals and commercial

transactions. All guilds were obligated to follow and respect these rules,

which included the right to fix prices and set standards for evaluating the

quality of goods that would be sold by tradesmen. Negotiations between the

representatives of the central government and the guild masters determined the

prices of goods and the criteria for judging the quality of a product. The

state involved itself in this process to ensure the collection of taxes from

each guild and to support the enforcement of the

ihtisab

laws and

regulations.

A market inspector, or a

muhtasib,

and his officers

were responsible for enforcing public morals and the established rules.

Strolling purposefully through the markets, they apprehended violators and

brought them to face the local

kadi

(religious judge). They enforced the

sentence handed down from the

kadi

by flogging or fining the violators.

According to Islamic traditions and practices, the

muhtasib

dealt

primarily with “matters connected with defective weights and measures,

fraudulent sales and non-payment of debts.” Commercial knavery “was especially

within his [the

muhtasib

’s] jurisdiction, and in the markets he had

supervision over all traders and artisans.” In addition to his police duties,

he also performed the duties of a magistrate. He could try cases summarily only

if the truth was not in doubt. As soon as a case involved claims and

counterclaims and “the evidence had to be sifted and oaths to be administered,”

disputes were referred to the

kadi.

The

muhtasib

was also the

official responsible for stamping certain materials, “such as timber, tile or

cloth, according to their standard and [he] prohibited the sale of unstamped

materials.”

A European observer who visited the Ottoman Empire at the

beginning of the 17th century described one form of punishment applied by the

muhtasib:

“Sometimes a cheat is made to carry around a thick plank with a hole cut in the

middle, so his head can go through it . . . Whenever he wants to rest, he has

to pay out a few aspers [silver coins]. At the front and back of the plank hang

cowbells, so that he can be heard from a distance. On top of it lies a sample

of the goods with which he has tried to cheat his customers. And as a

supposedly special form of mockery, he is made to wear a German hat.” As the

official responsible for the maintenance and preservation of public morals, the

muhtasib

had to ensure that men did not consort with women in public,

and it was his duty to identify and punish bad behavior, particularly stealing,

drunkenness, and wine drinking in public. A thief who was caught red-handed

would be nailed by his ears and feet to the open shutter of the shop he had

tried to rob. He was left in the same state for two days without food or water.

The

muhtasib

could take action against violations and offenses only if

they had been committed in public. He did not have the right to enter a house

and violate the privacy of a family.

BATHHOUSES

A “key resource of any Muslim city was its public baths.” A

“city was not considered to be a proper city by Muslim travelers in the

pre-modern period unless it had a mosque, a market, and a bathhouse.” Most “Ottoman

cities had a public bathhouse in every neighborhood,” which “provided not only

an opportunity for cleanliness but also a public space for relaxation and

entertainment.” This was “especially true for women, as men were allowed to

socialize in the coffee houses and public markets.”

As early as the 14th century, the North African traveler

Ibn Battuta observed that in Bursa, the Ottoman ruler Orhan had built two

bathhouses, “one for men and the other for women,” which were fed by a river of

“exceedingly hot water.” At bathhouses, or hammams, men had their “beards

trimmed or their hair cut,” while women “had their skin scrubbed, their feet

briskly massaged, and the whites and yolks of eggs . . . pressed around their

eyes to try to erase any wrinkles.” In its “steam-filled rooms and private

suites, young masseurs pummeled and oiled their clients as they stretched out

on the hot stones.”

With the conquest of the Balkans, the Ottomans introduced

their public baths to the peoples they had conquered. Hammams that received

their water from aqueducts were constructed in many towns. Some of these baths

were attached to the bazaars, where merchants, artisans, and shopkeepers were

attended by serving-boys. Salonika’s Bey Hammam, where visitors could still

wash themselves until the 1960s, is one of the outstanding examples of early

Ottoman culture and architecture.

Having recognized the benefits of cleanliness and to avoid

a needless trip to a public bath, the rich and the powerful built their own

private baths at home. Many “families allowed their relatives and retainers to

use” their private hammam, eliminating any need to use public baths. Despite

this development, the public baths remained popular among the masses who could

not afford building their own private bathhouse.