Read Daily Life In The Ottoman Empire Online

Authors: Mehrdad Kia

Daily Life In The Ottoman Empire (9 page)

Topkapi Palace, harem

(interior). Hall of the Padisha (Throne Room).

EUNUCHS

As in other Islamic states, in the Ottoman Empire, the

ruler maintained eunuchs or castrated males who were brought as slaves to guard

and serve the female members of the royal household. As Islam had forbidden

self-castration by Muslims or castration of one Muslim by another, the eunuchs

were bought in the slave markets of Egypt, the Balkans, and southern Caucasus.

In the palace, there were two categories of eunuchs—black and white. Black

eunuchs were Africans, mostly from Sudan, Ethiopia, and the east African

coastal region, who were sent to the Ottoman court by the governor of Egypt.

They served the female members of the royal family who resided in the sultan’s

harem. The white eunuchs were mostly white men imported from the Balkans and

the Caucasus and served the recruits at the palace school. The black eunuchs “underwent

the so-called radical castration, in which both the testicles and the penis

were removed,” whereas, in the case of eunuchs from the Balkans and the

Caucasus, “only the testicles were removed.”

An important figure in the Ottoman power structure was the

chief black eunuch, who served as the

kızlar ağası

(chief

of women) or

harem ağası

(chief of harem). In charge of the

harem and a large group of eunuchs who worked under his direct supervision, the

chief black eunuch enjoyed close proximity to the sultan and his family.

Another important figure was the chief of the white

eunuchs, who acted as

kapi ağası

(chief of the Gate of

Felicity). Starting with the reigns of Murad III (1574–1595) and Mehmed III

(1595–1603), the white eunuchs lost ground, and black eunuchs gained greater

control and access to the sultan. Regardless of their race, ethnic origin, or

the degree and intensity of castration, the palace eunuchs received

privileges—such as lavish clothing, accoutrements, and accommodations—in

keeping with their high status. Included among these privileges was access to

the best education available. It is not surprising, therefore, that many chief

eunuchs were avid readers and book collectors who established impressive

libraries.

The

ağa,

or the chief, of the black eunuchs of

the harem was not only responsible for the training and supervision of the

newly arrived eunuchs but also supervised the daily education and training of

the crown prince and “oversaw a massive network of pious endowments that

benefited the populations of and Muslim pilgrims to Mecca and Medina.” He used

his position and access to the throne to gain power and influence over the

sultan and government officials. His daily access to the sultan, and close

relationship with the mother and favorite concubines of his royal master, made

him an influential player in court intrigues. By the beginning of the 17th

century, the chief eunuch had emerged as one of the most powerful individuals

in the empire, at times second only to the sultan and the grand vizier and, in

several instances, second to none.

PALACE PAGES AND ROYAL CHAMBERS

Four principal chambers within the palace served the sultan

and his most immediate needs. The privy chamber served his most basic needs

such as bathing, clothing, and personal security. The sultan’s sword keeper (

silahdar

ağa)

, the royal valet (

çohadar ağa)

, and his personal

secretary (

sir katibi)

, were the principal officials in charge of the privy

chamber. The treasury chamber held the sultan’s personal jewelry and other

valuable items. The third chamber, the larder, was where the sultan’s meals

were prepared, and the fourth, or campaign chamber, was staffed by bathhouse

attendants, barbers, drumbeaters, and entertainers. Pages with exceptional

ability and talent would join the privy chamber after they had served in one of

the other three chambers. From the time the sultan woke up to the time he went

to bed, the pages of the privy chamber accompanied him and organized the many

services that their royal master required.

Surrounded and served as he was by an elaborate hierarchy

of pages, eunuchs, and attendants, access to the sultan became increasingly

difficult, and the number of individuals who could communicate directly with

him decreased significantly. One result was a rapid and significant increase in

the power of the royal harem. Starting in the second half of the 16th century,

the sultan’s mother and wives began to exercise increasing influence on the

political life of the palace and the decision making process. They enjoyed

direct access to the sultan and were in daily contact with him. With the sultan

spending less time on the battlefield and delegating his responsibilities to

the grand vizier, the mothers and wives began to emerge as the principal source

of information and communication between the harem and the outside world.

The majority of Ottoman sultans, however, were far from

simpleminded puppets of their mothers, wives, and chief eunuchs. In the

mornings, they attended to the affairs of their subjects, and in the evenings,

they busied themselves with a variety of hobbies and activities. According to

the Ottoman traveler and writer Evliya Çelebi, who served for a short time as a

page in the palace, Murad IV (1623–1640) had a highly structured routine in his

daily life, particularly during winter, when it was difficult to enjoy hunting

and horseback riding. In the mornings, he attended to the affairs of his

subjects. On Friday evenings, he met with scholars of religion and the readers

of the holy Quran and discussed various issues relating to religious sciences.

On Saturday evenings, he devoted his time to the singers who sang spiritual

tunes. On Sunday evenings, he assembled poets and storytellers. On Monday

evenings, he invited dancing boys and Egyptian musicians who performed till

daybreak. On Tuesday evenings, he invited to the palace old and experienced

men, upwards of seventy years, whose opinions he valued. On Wednesday evenings,

he gave audience to pious saints and on Thursday evenings, to

dervişes

(members

of Sufi or mystical orders).

As the Ottoman Empire entered the modern era, the everyday

life of the sultan also underwent a significant change. The slow and easygoing

lifestyle that prevailed at the harem of Topkapi and the large ceremonial

gatherings, which marked the visit by a foreign ambassador to the imperial

palace, gave way to a simple and highly disciplined routine characterized by

the informality of interaction between the sultan and his guests. Abdülhamid

II, who ruled from 1876 to 1909, awoke at six in the morning and dressed like

an ordinary European gentleman, wearing a frock coat, “the breast of which, on

great occasions,” was “richly embroidered and blazing with decorations.” He

worked with his secretaries until noon, when he sat for a light lunch. After

finishing his meal, the sultan took a short drive in the palace park or a sail

on the lake. Back at work, he gave audience to his grand vizier; various court

dignitaries; the ş

eyhülislam,

or the head of the ulema; and foreign

ambassadors. Having abandoned the ceremonial traditions of his predecessors who

ruled from Topkapi’s inner section, the sultan placed his visitor beside him on

a sofa and lighted a cigarette, which he offered to the guest. Since he could

speak only Turkish and Arabic, the sultan communicated with foreign ambassadors

and dignitaries through interpreters. At eight in the evening, Abdülhamid II

dined, sometimes alone and, at times, with a foreign ambassador. According to

one source, the dinner was “usually a very silent one” with dishes “served in

gorgeous style,

à la française,

on the finest of plate and the most

exquisite porcelain.” After dinner, the sultan sometimes played duets on the

piano with his younger children before he retired to the royal harem. He was

fond of light music.

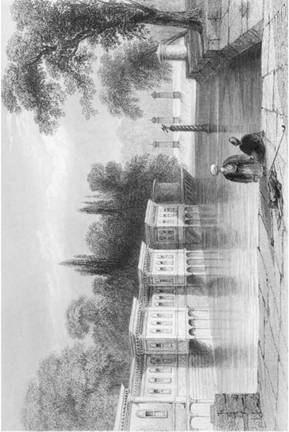

Palace of the Sweet Waters.

William H. Bartlett. From Pardoe, Julie,

The Beauties of the Bosphorus

(London

1839).

SULTAN IN PUBLIC

The people of the capital could watch their sultan each

Friday, leaving his palace for Aya Sofya, the grand mosque, where he prayed.

During the classical age of the empire, state dignitaries rode in front of

sultan with their proximity to their royal master determined by the position

they held at the court and in the government. Behind them rode the sultan’s

clean-shaven pages, “beardless and clothed in red livery.” The sultan was

surrounded by foot soldiers armed with bows and arrows, and “among these, certain

others again, with the office of courier and letter bearer, and therefore

running along most swiftly” and “dressed in scanty clothes, with the hems of

their coats in front shortened to the waist, and with their legs half bare: and

all of them, wearing livery according to their office, richly attired, and

looking charming with feathers decorating their hats.” Immediately behind the

sultan rode his sword keeper and the royal valet, whose offices were highly

esteemed among the Ottomans.

One of the principal functions of the state was waging war,

and military parades held before and after a campaign provided a popular

spectacle, which was attended by the sultan, his ministers, and thousands of

ordinary people. After war had been declared, all army units were assembled and

brought to order in an enclosure, where the grand vizier held a divan, or

council, that included all the dignitaries and high officials of the government

who were to accompany him on the campaign. Once the divan had completed its deliberations,

the grand vizier and company met with the sultan, who issued his dispatch and

final command. Upon leaving his audience with the sultan, the grand vizier

mounted his horse and, accompanied by the entire court and the army units,

which had awaited him in various courtyards, set off towards his first

encampment. If the campaign was in the east, the army crossed the Bosphorus

with galleys and rowboats that transported them to the Asian shore, where the

grand vizier waited, allowing his troops to arrive, equip themselves, and

prepare for the long journey ahead. Before the troops crossed the straits,

however, the people of Istanbul flocked to the windows of their homes or the

streets to cheer them on and bid them farewell. The sultan, surrounded by his

attendants and the members of the royal family, watched the event from a tower

attached to the outside walls of the palace.

The Italian traveler, Pietro della Valle (1586–1652), who

was in Istanbul from June 1614 to September 1615, described the military parade

organized on the occasion of a new Ottoman campaign against Iran. The parade

began with a display of large red and yellow flags held aloft by men on

horseback. Behind them, riding two by two came the palace officials and

couriers whose duty it was to deliver messages and execute orders (

çavuşes)

.

Gunners and bombardiers on foot followed, also two by two and armed with

scimitars and arquebuses. Behind them came armor-clad soldiers and men carrying

a variety of weapons, including “iron clad maces, axes, and swords with double

points or blades to each hilt.” Next came the

sipahis

(the cavalrymen),

armed with bows and arrows and dressed in their special garb, which was tucked

up and adorned with diverse skins of wild animals slung across them. The

acemi

oğlans

(young recruits to be trained as janissaries or the sultan’s

elite infantry corps) were led by their

ağa,

or commander, who was

a white eunuch. They were followed by the banners of the janissaries and the

captains of the janissary corps in pairs and armed with bows and arrows. Behind

their flags and captains marched thousands of janissaries packed closely

together. They led, by hand, water-bearing horses, adorned with grass and

flowers, and festooned with rags, tinsel, little flags, and ribbons. The

janissaries were followed by men carrying axes, hatchets, and wooden swords.

Then arrived pieces of artillery and galley boats, as well as regular foot

soldiers. Finally came their

ağa,

or commander, and the

dervişes

of the Bektaşi Sufi order, singing and shouting prayers for the

glorious army.

At the end of the parade came the horses of the grand

vizier led by his pages armed with bows and arrows with coats of mail under

their trappings or clothes. They were accompanied by the

kadis

(religious

judges) of Istanbul and Galata; the two

kadiaskers,

or the army judges

of Anatolia and Rumelia (the European provinces of the empire); the

müfti

(the

chief Muslim theologian) of Istanbul; and the viziers (ministers) of the

imperial council. Finally, the grand vizier himself rode in pomp and ceremony,

surrounded by a large number of foot soldiers, with the heron’s plume emblem of

his office adorning his turban. Behind the grand vizier appeared additional

sipahi

units with their own weapons, which were lances without hilts, bows,

arrows, and coats of mail. Behind them rode cavalrymen attached to the chief

minister who served as his bodyguards. These men wore antique helmets, buckles,

and golden stirrups, and their horses were caparisoned with cloth of gold

nearly to the ground.