Dare to Be a Daniel (3 page)

Read Dare to Be a Daniel Online

Authors: Tony Benn

Mother was scholarly, but she did not take a fundamentalist view of the Christian message or ever say or do anything that encouraged me to rebel. My brother Michael, who wanted to be a Christian minister after the war, set up his own prayer circle at school, and I drew great comfort from the knowledge of God watching over us. When I learned to fly, my mother told me that ‘underneath were the everlasting arms’,

implying

that even if I crashed, I was in the hands of the Almighty.

When my brother died in his plane, I found great comfort from praying for him and went to see the chaplain at the base in Africa where I was stationed to talk about it.

But, over the years, imperceptibly my faith has changed. I certainly was not influenced by atheistic arguments, which were extreme and threw doubt on the value of the Bible and the historical truth of Jesus’s life, and which mocked religious leaders, whose life of service entitled them to respect.

Inevitably a greater understanding of science, not least Darwin’s

On the Origin of Species

, played some part in undermining the idea that a kindly God and his Son could possibly have founded the universe, with billions of stars in our galaxy and billions of galaxies beyond us, whose origins could hardly have been explicable in that way.

But the real reason why my faith changed was the nature of the Church and the way in which it sought to use the teachings of the Bible to justify its power structures in order to build up its own authority.

For example, the idea of original sin is deeply offensive to me, in that I cannot imagine that any God could possibly have created the human race and marked it at birth with evil that could only be expiated by confession, devotion and obedience. This use of Christianity to keep people down was, I became convinced, destructive of any hope that we might succeed together in building a better world.

Of course what it did do was give the priests power over us, by hinting darkly that if we did not do what they told us to – and give money to the Church – we would rot in hell. Many of the

hymns

and prayers that I know and love contain ideas which have the same effect, and I came to repudiate them completely.

This did not in any sense involve accepting the implicit atheism of Marx, but when he spoke of religion being ‘the opium of the people’, it seemed to be a statement of my belief, without in any way demeaning the importance of the teachings of Jesus.

Indeed, I came to believe that Marx was the last of the Old Testament prophets, a wise old Jew sitting in the British Museum describing capitalism with clinical skill, but adding a moral dimension.

Das Kapital

could easily have been written in a completely factual way, describing exploitation as a part of the normal pattern of capitalism, without expressing any moral judgement on the matter. But Marx added a passion for justice that gave his work such unique political and moral power.

Also, the older I become, the more persuaded I am that organised religion can be a threat to the survival of the human race, and is fundamentally undemocratic in its structure and basically intolerant of those from other faiths, whom it sees as threatening its claim to contain the truth.

Political leaders can harness religious prejudice to justify their own policies and help sustain them in power, by claiming to speak with authority on behalf of those simple teachers who founded the religions which they purport to espouse. This is as true of President Bush and the Christian fundamentalists as it is of Osama bin Laden.

The ‘opium of the people’ exactly describes fundamentalist Muslims, evangelical American Christians who claim that God is on their side in a new crusade, and those Jews who believe that the Almighty granted them the right to own Palestine, as if God were an estate agent.

None of these charges of political ambition can be levelled at

the

simple men – whether Jewish, Christian or Muslim – who helped to teach us how to live in peace and who were united in one thing: there is only one God and we are all his children.

Another problem that I have tried to resolve, without repudiating what I learned as a child, is the idea of immortality, for my mother believed that when she died she would meet her parents, and my father and brother Michael, and that gave her great comfort. I never tried to dissuade her.

But for me immortality was meaningful in quite a different sense, in that ideas and the spirit survive physical death. As my dad used to say: ‘Every life is like a pebble dropped into a pool and the ripples go backwards and forwards for ever, even if we cannot see them.’

I see my parents in my brother David and myself, and I see my wife’s influence on my children and grandchildren; and we all feel the influence of teachers throughout history who have shaped our thinking and established the values that we attempt to uphold.

Here, in talking of teachers, I see Jesus the Carpenter of Nazareth as one of the greatest teachers, along with Moses and Mohammed. Christianity, Judaism and Islam are all monotheistic religions, teaching that we are brothers and sisters with a responsibility to each other.

My doubts are about the risen Christ and not about the importance of Jesus. Christians claim to have founded a Church in Jesus’s name, and my doubts are about this institution rather than about the teachings he left behind.

In part these doubts were influenced by my visit, while I was an RAF pilot on leave from Egypt, to Jerusalem in 1945. I went to the Church of the Holy Sepulchre and saw the Christian sects fighting over their right to a slice of the area where Christ’s body was supposed to have lain, and the stone on the top of the Mount

of

Olives in which a footprint on a rock was the last place on Earth that Jesus’s foot was supposed to have touched before ascending to heaven.

I have the deepest respect for those who believe in the virgin birth, the resurrection and the saints, but they do not help me to understand the world, nor do they point to my duty as to how one should live.

There is no wider theological gap than between those who believe that God created man and those who believe that man invented God. But the ethics of the humanist, the Christian, Jew or Muslim can be so close as to be almost indistinguishable.

I always ask people about their religious faith, and recently a man told me that he was a ‘lapsed atheist’ who did not believe in God, but had come to believe in the spirituality in all human beings and to respect it and believe that it had a value over and above what science could teach us about the world. I found that very convincing, because we must all try to lead a good life assisted by the prophets of the Old Testament, and Jesus and Mohammed.

Tom Paine said, ‘My country is the world and my religion is to do good,’ and added, ‘We have it in our power to start the world again.’ I have evolved from being a devout boy, through doubt and distrust in religious structures, to acceptance of the lessons the great religious teachers have taught.

I hope that my mother would have understood what I am trying to say and that, although my ideas have developed beyond what she taught me, she would recognise the influence she had on my journey of belief.

The role of conscience is a very interesting one: an imbued sense of right or wrong. At any one moment I know what I should do, even if I don’t do it; and I know what I shouldn’t do, even if

I

am doing it. It is a burden, but also a guide to the good life, helping me to see my way through the very complicated questions one has to deal with. It also embodies the idea of accountability. Whether you believe that you are accountable on the Day of Judgement for the way you have spent your life, or have to account to your fellow men and women for what you have done during your life, accountability is a strong and democratic idea.

The next part of this book describes my childhood and growing up within this social and political culture; the third part comprises speeches and essays on some of the moral and political challenges of recent times, reflecting the influence on my life of the dissenting tradition and the need always to question the conventional wisdom of the time.

Part Two

Then

1

Family Tree

THE FAMILY TRAIT

of stubbornness and independence can be traced back at least to my great-grandfather Julius, born in 1826. His father was a master quiltmaker in Manchester, and young Julius ran away from home because of difficulties with his father’s second wife; he walked the thirty miles to Liverpool and was found, according to a family autobiography, gazing into the Mersey by a passing Quaker. Urging Julius to follow him, the Quaker acquired lodgings for him and helped him with an education; Julius got a job as a teacher, then he married and at one time ran a boys’ ‘reformatory’ school in Northamptonshire. He later became a nonconformist – Congregational – minister.

On my mother’s side there was also a background of religious dissent and, interestingly, both families had a common entrepreneurial spirit and sense of public service.

The two family firms – Eadie Brothers, established by my great-grandfather Peter Eadie, and Benn Brothers, set up by my grandfather John Williams Benn – have both disappeared now, having been absorbed or wound up by bigger units, which saw the value of what they did, acquired them and lost the personal touch they embodied. Both firms were typical of Victorian imaginativeness combined with a sense of obligation to society, expressed by the individuals concerned serving in elected office. Peter Eadie became the Provost of Paisley and John Benn a founder member of the London County Council, MP for Tower Hamlets and Chairman of the LCC.

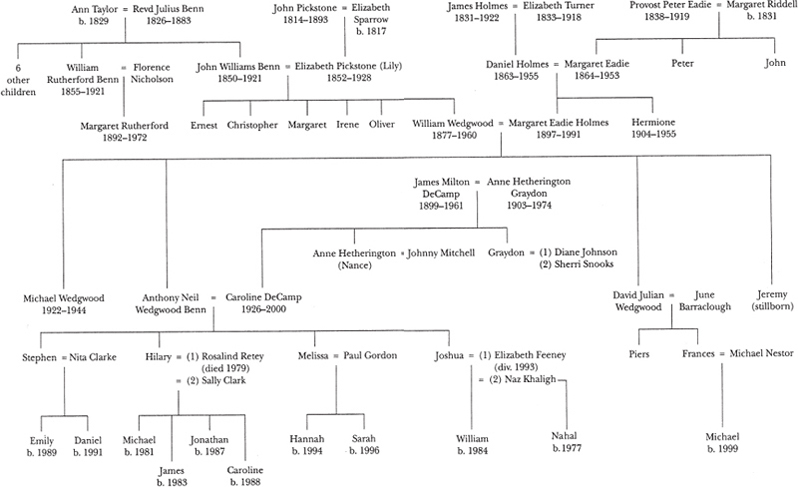

Benn Family Tree

I am very proud of my ancestors and, as a result, I have always had a great deal of sympathy for small businesses where the founder works alongside those he employs and in that sense is a worker himself. As Secretary of State for Industry, I tried to devise policies that would help small businessmen make their way with the minimum of difficulty, for they cannot employ a battery of lawyers and tax advisers, as the huge multinational corporations do – and they have to struggle with the administration and bureaucracy themselves, which can be most oppressive.

F

ATHER’S SIDE

It is said of Julius Benn that when, as a teacher, he took his students to an Anglican church one Sunday, the vicar attacked Martin Luther in his sermon. This enraged my great-grandfather, who rose from his pew and said to his little flock, ‘Boys, we leave the church at once,’ and they marched out of the church together. For this – and because he had lost money backing an unsuccessful invention – he was asked to leave the school and, with all their possessions in a wheelbarrow or pram, the family had to find lodgings. Julius later moved his family to London to the Mile End Road, where he worked as a newsagent and became the minister of the Gravel Pit Chapel in Hackney.

One of his children, John Benn (my grandfather), described the ‘reduced circumstances’ in which they lived. John went to work on his first day as an office boy in the City of London when he was eleven, wearing his mother’s pair of ‘Sunday boots’. Suffering some of the humiliations that many office boys experience, he wrote about this in his autobiography

The Joys of Adversity

.

John found himself employed by Lawes Randall and Co., a wholesale furniture company in City Road, as a junior invoice clerk. But he had a talent for art and practised drawing, inspired by the draughtsmen and designers, and later became a designer for the firm. By 1880 he had become a junior partner, and this enabled him to establish a little illustrated trade paper of his own, called

The Cabinet Maker

. This struggling business kept him going, despite regular financial difficulties, and he earned extra money later by lecturing, during which he would draw lightning-quick sketches of prominent figures; he also drew sketches of his parliamentary colleagues after he had been elected as a Liberal MP in 1892. At his peak John was earning £2,000 per year from lectures. One of his sketches showed housing in Bethnal Green: