Darjeeling (51 page)

Authors: Jeff Koehler

Dr. Nathaniel Wallich was superintendent of the East India Company’s botanic garden in Calcutta for three decades and was at its helm when wild tea was found growing in Assam. Considered the Empire’s nursery, the garden was fundamental in developing a tea industry on the subcontinent. (Wellcome Library)

The Scottish plant hunter Robert Fortune added, by his own estimation, nearly twenty thousand Chinese tea plants to the young Indian industry, giving it the quality it desired. (© President and Fellows of Harvard College, Arnold Arboretum Archives)

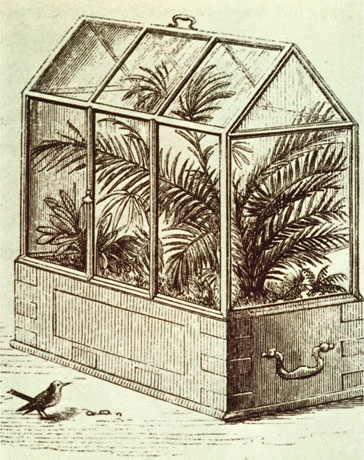

Robert Fortune gradually perfected the technique for sending tea plants and seeds from China to India in glass Wardian cases.

The charismatic Rajah Banerjee tastes some of Makaibari Tea Estate’s iconic teas. His family owned Darjeeling’s most famous garden for more than 150 years. (Getty Images)

Winding up through tea estates, the road to Darjeeling from the plains is slow, steep, and scenic.

Ambootia Tea Estate, one of Darjeeling’s biodynamic gardens

Makaibari Tea Estate, just below Kurseong. On clear days, the view stretches down to the plains.

Sanjay Sharma inspects a field of young tea interwoven with blossoming marigolds on Glenburn Tea Estate.

Autumn on the Ging Tea Estate with the snow-capped Himalayas in the background

The view from Glenburn Tea Estate of Mt. Kanchenjunga. At 28,169 feet, it’s the world’s third-tallest peak behind Everest and K2.

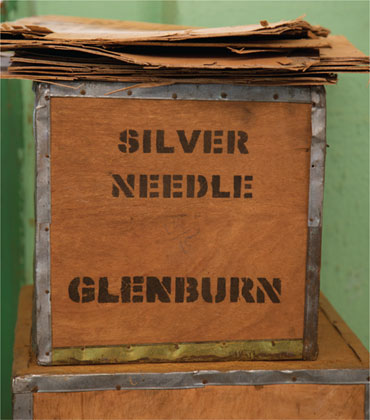

High-end specialty teas like Glenburn Tea Estate’s Silver Needle have recently become an important part of many gardens’ portfolios. These are packed in traditional wooden chests to prevent breakage.

A classic Darjeeling pluck consists of just the tender first two leaves and a still-curled bud. It takes about twenty-two thousand of these to make a single kilogram of tea.

Tea pluckers working a section of Castleton Tea Estate during the first flush.