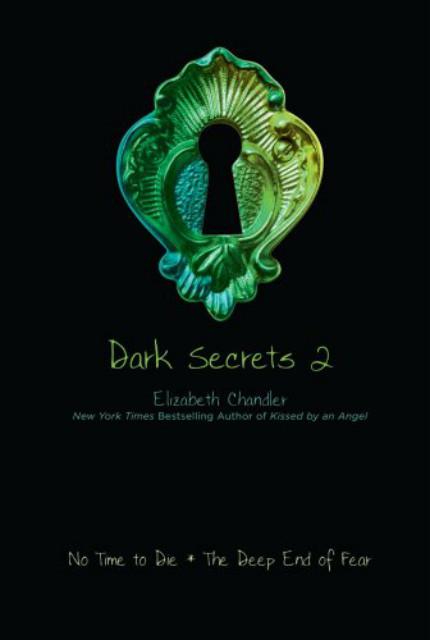

Dark Secrets 2: No Time to Die; The Deep End of Fear

Read Dark Secrets 2: No Time to Die; The Deep End of Fear Online

Authors: Elizabeth Chandler

Tags: #Murder, #Actors and Actresses, #Problem Families, #Family, #Dysfunctional Families, #Juvenile Fiction, #Family Problems, #Horror Tales; American, #Fiction, #Interpersonal Relations, #Death, #Actors, #Teenagers and Death, #Tutors and Tutoring, #Sisters, #Horror Stories, #Ghosts, #Camps, #Young Adult Fiction; American, #Mystery and Detective Stories

Table of Contents

Chapter 1

Chapter 2

Chapter 3

Chapter 4

Chapter 5

Chapter 6

Chapter 7

Chapter 8

Chapter 9

Chapter 10

Chapter 11

Chapter 12

Chapter 13

Chapter 14

Chapter 15

Chapter 16

Chapter 17

Chapter 18

Chapter 19

Chapter 20

Chapter 1

Chapter 2

Chapter 3

Chapter 4

Chapter 5

Chapter 6

Chapter 7

Chapter 8

Chapter 9

Chapter 10

Chapter 11

Chapter 12

Chapter 13

Chapter 14

Chapter 15

Chapter 16

Chapter 17

Chapter 18

Chapter 19

Chapter 20

Chapter 21

Chapter 22

Chapter 23

Chapter 24

PART I: No Time to Die

Chapter 1

Jenny? Jenny, are you there? Please pick up the phone, Jen. I have to talk to you. Did you get my e-mail? I don't know what to do. I think I'd better leave Wisteria.

Jenny, where are you? You promised you'd visit me. Why haven't you come? I wish you'd pick up the phone.

Okay, listen, I have to get back to rehearsal. Call me. Call me soon as you can.

I retrieved my sister's message about eleven o'clock that night when I arrived home at our family's New York apartment. I called her immediately, if somewhat reluctantly. Liza was a year ahead of me, but in many ways I was the big sister, always getting her out of her messes—and she got in quite a few.

Thanks to her talent for melodrama, my sister could turn a small misunderstanding in a school cafeteria into tragic opera.

Though I figured this was one more overblown event, I stayed up til two A.M., dialing her cell phone repeatedly. Early the next morning I tried again to reach her. Growing uneasy, I decided to tell Mom about the phone message. Before I could, however, the Wisteria police called. Liza had been found murdered.

Eleven months later Sid drove me up and down the tiny streets of Wisteria, Maryland. "I don't like it. I don't like it at all," he said.

"I think it's a pretty town," I replied, pretending not to understand him. "They sure have enough flowers."

"You know what I'm saying, Jenny."

Sid was my father's valet and driver. Years of shuttling Dad back and forth between our apartment and the theater, driving Liza to dance and voice lessons and me to gymnastics, had made him part of the family.

"Your parents shouldn't have let you come here, that's what I'm saying."

"Chase College has a good summer program in high school drama," I pointed out.

"You hate drama."

"A person can change, Sid," I replied—not that I had.

"You change? You're the steadiest, most normal person in your family."

I laughed. "Given my family, that's not saying much."

My father, Lee Montgomery, the third generation of an English theater family, does everything with a flair for the dramatic. He reads grocery lists and newspaper ads like Shakespearean verse. When he lifts a glass from our dishwasher to see if it's clean, he looks like Hamlet contemplating Yorick's skull. My mother, the former Tory Summers, a child and teen star who spent six miserable years in California, happily left that career and married the next one, meaning my father. But she is still an effusive theater type—warm and expressive and not bound by things like facts or reason. In many ways Liza was like Mom, a butterfly person.

I have my mother's red hair and my father's physical agility, but I must have inherited some kind of mutated theater gene: I get terrible stage fright.

"I don't think it's safe here," Sid went on with his argument.

"The murder rate is probably one tenth of one percent of New York's," I observed. "Besides, Sid, Liza's killer has moved north. New Jersey was his last hit. I bet he's waiting for you right now at the Brooklyn Bridge." Sid grunted. I was pretty sure I didn't fool him with my easy way of talking about Liza's murderer. For a while it had helped that her death was the work of a serial killer, for the whole idea was so unreal, the death so impersonal, I could keep the event at a distance—for a while.

Sid pulled over at the comer of Shipwrights Street and Scarborough Road, as I had asked him to, a block from the college campus. Before embarking on this trip I had checked out a map of Maryland's Eastern Shore. Wisteria sat on a piece of land close to the Chesapeake Bay, bordered on one side by the Sycamore River and on the other two by large creeks, the Oyster and the Wist. I had plotted our approach to the colonial town, choosing a route that swung around the far end of Oyster Creek, so we wouldn't have to cross the bridge. Liza had been murdered beneath it.

Sid turned off the engine and looked at me through the rearview mirror. "I've driven you too many years not to get suspicious when you want to be left off somewhere other than where you say you're going."

I smiled at him and got out. Sid met me at the back of the long black sedan and pulled out my luggage. It was going to be a haul to Drama House.

"So why aren't I taking you to the door?"

"I told you. I'm traveling incognito."

He rolled his eyes. "Like

I'm

famous and they'll know who you are when they see me dropping you off. What's the real reason, Jenny?"

"I just told you—I don't want to draw attention to myself."

In fact, my parents had agreed to let me attend under a different last name. My mother, after recovering from the shock that I wanted to do theater rather than gymnastics, had noted that the name change would reduce the pressure. My father thought that traveling incognito bore the fine touch of a Shakespearean romance.

They were less certain about my going to the town of Wisteria, to the same camp Liza had. But my father was doing a show in London, and I told them that, at seventeen, I was too old to hang out and do nothing at a hotel. Since I had never been to Wisteria, it would have fewer memories to haunt me than our New York apartment and the bedroom I had shared with Liza.

I put on my backpack and gave Sid a hug. "Have a great vacation! See you in August."

Tugging on the handle of my large, wheeled suitcase, I strode across the street in the direction of Chase campus, trying hard not to look at Sid as he got in the car and drove away. Saying goodbye to my parents at the airport had been difficult this time; leaving Sid wasn't a whole lot easier. I had learned that temporary goodbyes can turn out to be forever.

I dragged my suitcase over the bumpy brick sidewalk. Liza had been right about the humidity here. At the end of the block I fished an elastic band from my backpack and pulled my curly hair into a loose pony-tail.

Straight ahead of me lay the main quadrangle of Chase College, redbrick buildings with steep slate roofs and multipaned windows. A brick wall with a lanterned gate bordered Chase Street. I passed through the gate and followed a tree-lined path to a second quad, which had been built behind the first.

Its buildings were also colonial in style, though some appeared newer. I immediately recognized the Raymond M. Stoddard Performing Arts Building.

Liza had described it accurately as a theater that looked like an old town hall, with high, round-topped windows, a slate roof, and a tall clock tower rising from one comer. The length of the building ran along the quad, with the entrance to the theater at one end, facing a parking lot and college athletic fields.

I had arrived early for our four o'clock check-in at the dorms. Leaving my suitcase on the sidewalk, I climbed the steps to the theater. If Liza had been with me, she would have insisted that we go in. Something happened to Liza when she crossed the threshold of a theater—it was the place she felt most alive.

Last July was the first time my sister and I had ever been separated. After middle school she had attended the School for the Arts and I a Catholic high school, but we had still shared a bedroom, we had still shared the details of our lives. Then Liza surprised us all by choosing a summer theater camp in Maryland over a more prestigious program in the New York area, which would have been better suited to her talent and experience. She was that desperate to get away from home.

Once she got to Wisteria, however, she missed me. She e-mailed every day and begged me to come and meet her new friends, especially Michael. All she could talk about was Michael and how they were in love, and how this was love like no one else had ever known. I kept putting off my visit. I had lived so long in her shadow, I needed the time to be someone other than Liza Montgomery's sister. Then suddenly I was given all the time in the world.

For the last eleven months I had struggled to concentrate in school and gymnastics and worked hard to convince my parents that everything was fine, but my mind and heart were somewhere else. I became easily distracted. I kept losing things, which was ironic, for I was the one who had always found things for Liza.

Without Liza, life had become very quiet, and yet I knew no peace. I could not explain it to my parents—to anyone—but I felt as if Liza's spirit had remained in Wisteria, as if she were waiting for me to keep my promise to come.

I reached for the brass handle on the theater door and found the entrance unlocked. Feeling as if I were expected, I went in.

Chapter 2

Inside the lobby the windows were shuttered and only the Exit signs lit. Having spent my childhood playing in the dusky wings and lobbies of half-darkened theaters, I felt right at home. I took off my backpack and walked toward the doors that led into the theater itself. They were unlocked and I slipped in quietly.

A single light was burning at the back of the stage. But even if the place had been pitch black, I would have known by its smell—a mix of mustiness, dust, and paint—that I was in an old theater, the kind with worn gilt edges and heavy velvet curtains that hung a little longer each year. I walked a third of the way down the center aisle, several rows beyond the rim of the balcony, and sat down. The seat was low-slung and lumpy.

"I'm here, Liza. I've finally come."

A sense of my sister, stronger than it had been since the day she left home, swept over me. I remembered her voice, its resonance and range when she was onstage, its merriment when she would lean close to me during a performance, whispering her critique of an actor's delivery: "I could drive a truck through that pause!"

I laughed and swallowed hard. I didn't see how I could ever stop missing Liza. Then I quickly turned around, thinking I'd heard something.

Rustling. Nothing but mice, I thought; this old building probably housed a nation of them. If someone had come through the doors, I would have felt the draft.

But I continued to listen, every sense alert. I became aware of another sound, soft as my own breathing, a murmuring of voices. They came from all sides of me—girls' voices, I thought, as the sound grew louder. No—one voice, overlapping itself, an eerie weave of phrases and tones, but only one voice.

Liza's.

I held still, not daring to breathe. The sound stopped. The quiet that followed was so intense my ears throbbed, and I wasn't sure if I had heard my dead sister's voice or simply imagined it. I stood up slowly and looked around, but could see nothing but the Exit signs, the gilt edge of the balcony, and the dimly lit stage.

"Liza?"

There had always been a special connection between my sister and me. We didn't look alike, but when we were little, we tried hard to convince people we were twins. We were both left-handed and both good in languages. According to my parents, as toddlers we had our own language, the way twins sometimes do. Even when we were older, I always seemed to know what Liza was thinking. Could something like that survive death?

No, I just wanted it to; I refused to let go.

I continued down the aisle and climbed the side steps up to the proscenium stage. Its apron, the flooring that bows out beyond the curtain line, was deep. If Liza had been with me, she would have dashed onto it and begun an impromptu performance. I walked to the place that Liza claimed was the most magical in the world—front and center stage—then faced the rows of empty seats.

I'm here, Liza, I thought for a second time.

After she died, I had tried to break the habit of mentally talking to her, of thinking what I'd tell her when she got home from school. It was impossible.

I've come as I promised, Liza.

I rubbed my arms, for the air around me had suddenly grown cold. Its heaviness made me feel strange, almost weightless. My head grew light. I felt as if I could float up and out of myself. The sensation was oddly pleasant at first. Then my bones and muscles felt as if they were dissolving. I was losing myself—I could no longer sense my body. I began to panic.

The lights came up around me, cool-colored, as if the stage lights had been covered with blue gels. Words sprang into my head and the lines seemed familiar, like something I had said many times before:

O time, thou must untangle this knot, not I. It is too hard a knot for me t'untie.

In the beat that followed I realized I had spoken the lines aloud.

"Wrong play."

I jumped at the deep male voice.

"We did that one last year."

I spun around.

"Sorry, I didn't mean to scare you."

The blue light faded into ordinary house and overhead stage lighting. A tall, lean guy with sandy-colored hair, my age or a little older, set down a carton.

He must have turned on the lights when entering from behind the stage. He strode toward me, smiling, his hand extended. "Hi. I'm Brian Jones."

"I'm Jenny." I struggled to focus on the scene around me. "Jenny Baird."

Brian studied me for a long moment, and I wondered if I had sounded unsure when saying my new last name. Then he smiled again. He had one of those slow-breaking, tantalizing smiles. "Jenny Baird with the long red hair. Nice to meet you. Are you here for camp?"

"Yes. You, too?"

"I'm always here. This summer I'm stage manager." He pulled a penknife from his pocket, flicked it open, and walked back to the carton. Kneeling, he inserted the knife in the lid and ripped it open. "Want a script? Are you warming up for tomorrow?"

"Oh, no. I don't act. I'm here to do crew work."

He gave me another long and curious look, then pulled out a handful of paperback books, identical copies of

A Midsummer Night's Dream. "I

guess you don't know about Walker," he said, setting the books down in sets of five. "He's our director and insists that everyone acts."

"He can insist, but it won't do him any good," I replied. "I have stage fright. I can act if I'm in a classroom or hanging out with friends, but put me on a stage with lights shining in my face and an audience staring up at me, and something happens."

"Like what?" Brian asked, sounding amused.

"My voice gets squeaky, my palms sweat. I feel as if I'm going to throw up. Of course," I added, "none of my elementary school teachers left me on stage long enough to find out if I would."

He laughed.

"It's humiliating," I told him.

"I suppose it would be," he said, his voice gentler. "Maybe we can help you get over it."

I walked toward him. "Maybe you can explain to the director that I can't."

He gazed up at me, smiling. His deep brown eyes could shift easily between seriousness and amusement. "I'll give it a shot. But I should warn you, Walker can be stubborn about his policies and very tough on his students. He prides himself on it."

"It sounds as if you know him well." Had Brian known Liza, too? I wondered.

"I'm going to be a sophomore here at Chase," Brian replied, "and during my high school years I was a student at the camp, an actor. Did you see our production last year?"

"No. What play did you do?"

"The one you just quoted from," he reminded me.

For a moment I felt caught.

"Twelfth Night"

"Those were Viola's lines," he added.

Liza's role. Which was how I knew the lines—I'd helped her prepare for auditions.

Still, the way Brian studied me made me uncomfortable. Did he know who I was? Don't be stupid, I told myself. Liza had been lanky and dark-haired, like my father, while my mother and I looked as if we had descended from leprechauns. Liza's funeral had been private, with only our closest friends and family invited. My mother had always protected me from the media.

"It's a great play," I said. "My school put it on this year," I added, to explain how I knew the lines.

Brian fel silent as he counted the books. "So where will you be staying?" he asked, rising to his feet. "Did they mail you your room assignment?" "Yes.

Drama House." "Lucky you!"

"I don't like the sound of that." He laughed. "There are four houses being used for the camp," he explained. "Drama House, a sorority, and two frats. I'm the R.A., the resident assistant, for one frat. Two other kids who go to Chase will be the R.A.S for the other frat and the sorority house. But you and the girls at Drama House will have old Army Boots herself. I think last year's campers had more descriptive names for her."

Liza had, but Liza was never fond of anyone who expected her to obey rules. "Is she that awful?" I asked. He shrugged.

"I

don't think so. But of course, she's my mother."

I laughed, then put my hand over my mouth, afraid to have hurt his feelings.

He reached out and pulled my hand away, grinning. "Don't hide your smile, Jenny. It's a beautiful one."

I felt my cheeks growing warm. Again I became aware of his eyes, deep brown, with soft, dusty lashes.

"If you wait while I check out a few more supplies, I'll walk you to Drama House."

"Okay."

Brian headed backstage. I walked to the edge of the apron and sat down, swinging my feet against the stage, gazing into the darkness, wondering.

Brian had heard me say Liza's lines, but he hadn't mentioned the voices that I'd heard sitting in the audience. I thought of asking him about them but didn't want to sound crazy.

But it's not crazy, I told myself. It shouldn't have surprised me that being in a place where I couldn't help but think of Liza, I'd remember her lines. It was only natural that, missing her so, I would imagine her voice.

Then something caught my eye, high in the balcony, far to the right, a flicker of movement. I strained to see more, but it was too dark. I stood up quickly.

A sliver of light appeared—a door at the side of the balcony opened and a dark figure passed through it. Someone had been sitting up there.

For how long? I wondered. Since the rustling I had heard when I first came in?

"Is something wrong?" Brian asked, reemerging from the wings.

"No. No, I just remembered I left my luggage at the front door."

"It'll be okay. I'll show you the back door—that's the one everybody uses—then you can go around and get it."

He led me backstage, where he turned out all but the light that had been burning before, then we headed down a flight of steps. The exit was at the bottom.

"This door is usually unlocked," Brian said. "People from the city always think it's strange the way we leave things open, but you couldn't be in a safer town."

Aside from an occasional serial killing, I thought.

We emerged into an outside stairwel that was about five steps below ground level. Across the road from the theater, facing the back of the college quadrangle, was a row of large Victorian houses. A line of cars had pulled up in front of them, baggage was deposited on sidewalks, and kids were gathering on the lawns and porches. Someone waved and called to Brian.

"Catch you later, Jenny," he said, and started toward the houses.

I headed toward the front of Stoddard to fetch my luggage. As I rounded the corner I came face to face with someone. We both pulled up short. The guy was my age, tall with black hair, wearing a black T-shirt and black jeans. He glanced at me, then looked away quickly, but I kept staring. He had the most startlingly blue eyes.

"Sorry," he said brusquely, then walked a wide route past me.

I turned and watched him stride toward the houses across the street.

I knew that every theater type has a completely black outfit in his closet, maybe two, for black is dramatic and tough and cool. But it's also the color to wear if you don't want to be seen in the dark, and this guy didn't want to be seen, not by me. I had sensed it in the way he'd glanced away. He'd acted guilty, as if I had caught him at something, like slinking out of the balcony, I thought.

Had he heard Liza's voice? Had he been responsible for it? A tape of her voice, manipulated by sound equipment and played over the theater's system could have produced what I heard.

There was just one problem with this explanation—it begged another. Why would anyone want to do that?