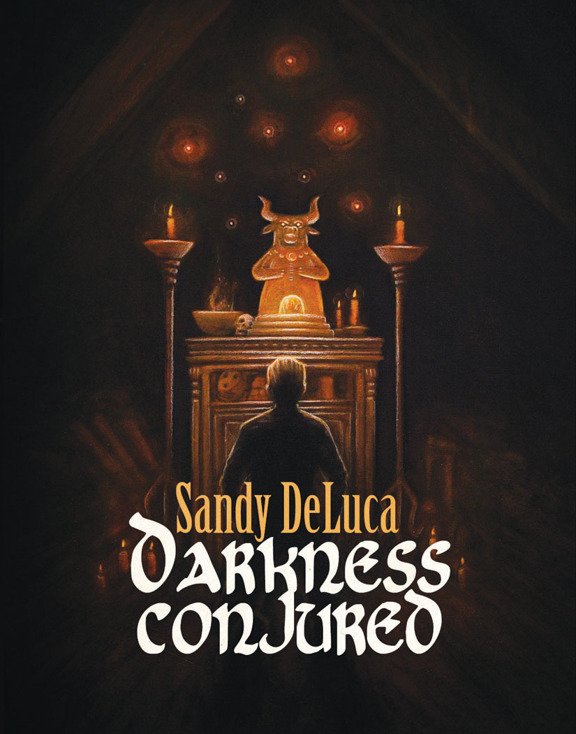

Darkness Conjured

Authors: Sandy DeLuca

DARKNESS CONJURED

Sandy DeLuca

FIRST EDITION

Darkness Conjured

© 2011 by Sandy DeLuca

© 2011 by Sandy DeLuca

Cover Artwork © 2011 by Zach McCain

All Rights Reserved.

This book is a work of fiction. Names, characters, places and incidents are either a product of the author’s imagination or are used fictitiously. Any resemblance to actual events, locales or persons, living or dead, is

entirely coincidental.

entirely coincidental.

DELIRIUM BOOKS

P.O. Box 338

North Webster, IN 46555

www.deliriumbooks.com

Acknowledgements: Thanks to Greg F. Gifune for helping me to hone my craft. Rob

Dunbar just for being Ron Dunbar. Shane Ryan Staley for all that he does. Matt

and Julie for their love and support.

Dunbar just for being Ron Dunbar. Shane Ryan Staley for all that he does. Matt

and Julie for their love and support.

For Gianna and Sophia...

and for KR wherever you are

I wish you could know them...

“In 1968, they were teenage girls, unwed and pregnant. Shunned by family and

society at large, like countless women of their generation, they were forced to

give up their babies...”

society at large, like countless women of their generation, they were forced to

give up their babies...”

People Magazine

September 18, 2006

Volume 66, Number 12

Author Notes:

This story is based loosely on incidents that occurred decades ago. I’m not sure if the ghost tales are real, but they stirred my imagination. The

Amelia Leech Home is a product of my imagination. The

unwed mother

was branded as a shameful figure in the sixties. Deeds and pregnancies were

hidden. This is a story about the sadness regarding that notion. It is also a tale of terror.

Amelia Leech Home is a product of my imagination. The

unwed mother

was branded as a shameful figure in the sixties. Deeds and pregnancies were

hidden. This is a story about the sadness regarding that notion. It is also a tale of terror.

Parts of this novella are loosely based writings of John Dee and his Angelic

Magic and Moloch from

Milton’s Paradise Lost

.

Magic and Moloch from

Milton’s Paradise Lost

.

1

February 11th, 1968

The Amelia Leech Home is haunted by those who lived and died here. Decades of

terror permeate. Hopeless cries erupt from behind bolted doors.

terror permeate. Hopeless cries erupt from behind bolted doors.

I hear whispers when walking up stairs after sundown. I’ve seen figures out of the corner of my eye—passing by a window—or by an open door. The dead in perpetual anguish.

Living residents are tormented as well. There are bullies and thieves—stealing from my room—destroying things dear to me. My good wool blazer has vanished. Photographs of

my family kept on my bureau have been smeared with feces. I’ve learned to hide what’s sacred behind wooden planks in my closet.

my family kept on my bureau have been smeared with feces. I’ve learned to hide what’s sacred behind wooden planks in my closet.

My room is small. I sleep on a shabby bed. There’s a small bureau near a grimy window and an old braided rug in the middle of the

scratched wooden floor. My room is one of many in this monstrous structure.

scratched wooden floor. My room is one of many in this monstrous structure.

My father sent me here. He wants my pregnancy hidden. He says the baby

has

to be adopted once it’s born. He told me, “I don’t want people mocking you. We’ll deal with it as best as we can.”

has

to be adopted once it’s born. He told me, “I don’t want people mocking you. We’ll deal with it as best as we can.”

My mother cries a lot. She swears a trio of soothsayers have come to claim a

satanic debt.

satanic debt.

My sisters are silent most times.

I’m not like them. I need to do what’s right for me. I don’t care what people think.

I’m almost twenty—older than most of the girls here. I can work as a waitress and get government

assistance. I am prepared for a life of ridicule and poverty.

assistance. I am prepared for a life of ridicule and poverty.

I touch my stomach and think about where I came from. I wonder where I’m headed.

Is that the wind howling—or something crying out from the bowels of this house? I’m terrified of night and I regret things I’ve done.

I wish I’d never met Ken, that I’d never agreed to go with him on that steamy day in August, but I was lonely,

tired of spending nights with my mother while my father wagered bets and

shuffled cards in smoky back rooms. I wonder what evil alliances he made over

the years and if my flesh and blood has been offered in sacrifice.

tired of spending nights with my mother while my father wagered bets and

shuffled cards in smoky back rooms. I wonder what evil alliances he made over

the years and if my flesh and blood has been offered in sacrifice.

* * *

I am the youngest of three girls. My first memories are of days spent living in

a tenement house on the poor side of town. I remember my sisters Beth and Jen

going to school in early morning. My mother worked in the city’s only surviving soap factory. Sometimes she put in ten hour days. Back then my

father stayed home, took care of the house and made sure we were fed.

a tenement house on the poor side of town. I remember my sisters Beth and Jen

going to school in early morning. My mother worked in the city’s only surviving soap factory. Sometimes she put in ten hour days. Back then my

father stayed home, took care of the house and made sure we were fed.

My toys were handed down from my sisters. My only friend was my father when my

sisters were not around.

sisters were not around.

Dad and I would sit in our living room after the house had been cleaned and the

breakfast dishes done. There were stacks of books piled at his side. He’d read to me, but I didn’t understand the words, or exotic names he pronounced. After lunch he’d climb up to the attic, with me at his heels. Vague memories of burning candles

and the smell of dampness still linger. An odd piece of jewelry, with even

odder symbols, hung around my dad’s neck. Sometimes he’d remove a ceramic figure from beneath a wrinkled scarf. Terra Cotta. Painted

face and long graceful limbs. Creepy, mysterious and beautiful all at once.

breakfast dishes done. There were stacks of books piled at his side. He’d read to me, but I didn’t understand the words, or exotic names he pronounced. After lunch he’d climb up to the attic, with me at his heels. Vague memories of burning candles

and the smell of dampness still linger. An odd piece of jewelry, with even

odder symbols, hung around my dad’s neck. Sometimes he’d remove a ceramic figure from beneath a wrinkled scarf. Terra Cotta. Painted

face and long graceful limbs. Creepy, mysterious and beautiful all at once.

“What are you doing, Daddy?” I’d asked him.

“Praying to angels. Lailah is your guardian angel. She watched over you when you

were born,” he’d tell me and then he’d begin to read from an old book.

were born,” he’d tell me and then he’d begin to read from an old book.

Sometimes orbs of light floated over his head. Most times everything was silent

and he’d snuff out the candles only to make his way back downstairs.

and he’d snuff out the candles only to make his way back downstairs.

I don’t know if he continued his prayers as I grew older. I only know he began to go

out nightly after my mother’s heart attack. He grew quiet, distant and reluctantly did odd jobs during the

day.

out nightly after my mother’s heart attack. He grew quiet, distant and reluctantly did odd jobs during the

day.

Always before midnight I’d hear his footsteps on the attic stairs. I wondered if his vigils turned darker

when I heard sounds erupting from the attic and saw dark shapes drifting by my

window.

when I heard sounds erupting from the attic and saw dark shapes drifting by my

window.

Years went by. Diabetes and rheumatoid arthritis added to my mother’s already fragile health. My father grew bitter, sometimes downright cruel. By

my nineteenth birthday he barely spoke to me, except to criticize or scold.

Yet, once in a while, he’d smile at me like he did when I was little.

my nineteenth birthday he barely spoke to me, except to criticize or scold.

Yet, once in a while, he’d smile at me like he did when I was little.

There were no smiles when I dropped out of business school. I was tired of

struggling with Economics and Accounting—tired of my father reminding me that my sister Beth was getting her Masters and

my sister Jen had given birth to her second child, happily married to her high

school sweetheart.

struggling with Economics and Accounting—tired of my father reminding me that my sister Beth was getting her Masters and

my sister Jen had given birth to her second child, happily married to her high

school sweetheart.

My dad told me, “Took hard earned money to further your education. If you can’t make it in school then it’s best you find a husband. You’ll never survive on a woman’s paycheck. Lots of guys in town ask about you.” I thought about the guys my father knew. I’d take my chances in life without them.

My mother would hug me and say, “There’s somebody out there for you, Meg.”

I wondered where and how I’d meet this

somebody

. I had visions of being thirty, still unmarried and living with my parents. I

told myself I wouldn’t let that happen, but I let down my guard and got into this mess.

somebody

. I had visions of being thirty, still unmarried and living with my parents. I

told myself I wouldn’t let that happen, but I let down my guard and got into this mess.

I was bored with staying home on weekends while others were out dancing. The

drinking age is twenty-one, but fake IDs and sweet talking bouncers cure that

problem for girls my age.

drinking age is twenty-one, but fake IDs and sweet talking bouncers cure that

problem for girls my age.

My father forbade me to go to nightclubs. He said I’d only meet bums, guys who liked to drink and party. He said girls who went to

bars

were tramps. He’d heard stories about casual sex in back seats of cars. I figured I’d get a taste for what Dad forbade once I saved up and was far away from him.

bars

were tramps. He’d heard stories about casual sex in back seats of cars. I figured I’d get a taste for what Dad forbade once I saved up and was far away from him.

Most of the guys who frequent clubs are in college, or their birth dates haven’t been selected by the draft. However, turmoil over the war in ’Nam made rebels out of others. In 1967 burning draft cards became vogue and

hippies made Haight Ashbury in San Francisco their Mecca. It seemed every time

I turned on the radio Aretha Franklin was singing,

Respect.

hippies made Haight Ashbury in San Francisco their Mecca. It seemed every time

I turned on the radio Aretha Franklin was singing,

Respect.

I wish I’d had more respect for myself.

* * *

I didn’t eat much for dinner, just a bowl of soup and some toast. Now I’m starving.

I rise from my bed, put on my robe and open my door a crack. The hall is dark.

The house is quiet, but for the furnace kicking in and soft whispers behind

closed doors.

The house is quiet, but for the furnace kicking in and soft whispers behind

closed doors.

I gingerly climb down the stairs, passing creepy photographs hanging on walls. I

don’t dare look at them. Sometimes, even in day, eyes seem to move and lips curl

with demonic smiles. Sometimes I hear the floor creak behind me. Other times an

eerie sigh erupts.

don’t dare look at them. Sometimes, even in day, eyes seem to move and lips curl

with demonic smiles. Sometimes I hear the floor creak behind me. Other times an

eerie sigh erupts.

I hear that sigh now. I stop and slowly turn. No one is there and I wonder if an

unseen entity hovers at the top of the stairs.

unseen entity hovers at the top of the stairs.

With a pounding heart I look from right to left. I see nothing but dark and

flickering shadows.

flickering shadows.

I convince myself it’s Marcy Long trying to spook me. She scared the heck out of Linda Sinelli the

other morning. Snuck in the bathroom while Linda was showering, pulled open the

curtains and taunted her with a kitchen knife.

other morning. Snuck in the bathroom while Linda was showering, pulled open the

curtains and taunted her with a kitchen knife.

Marcy nicked Linda’s arm and legs before her screams brought Maureen Dugan, the home’s social worker, to the rescue. I wonder what would have happened if no one

heard.

heard.

They took the knife away, but rumor has it Marcy’s got others hidden. I’m not sure why they don’t just send her back to Juvie.

I imagine Marcy creeping behind me, hiding in shadow and caressing the blade of

a knife. I hear soft laughter and walk faster. I don’t dare turn around for fear of what I’ll see.

a knife. I hear soft laughter and walk faster. I don’t dare turn around for fear of what I’ll see.

Once at the bottom of the stairs I feel relief. I move past tables where potted

snake plants are displayed in antique vases. I hear a soft snore. It’s Mr. Greely, the home’s handyman. He’s asleep in a chair propped against the door to the library. I’m reminded of my old Grandpa George, resting after he tended his garden.

snake plants are displayed in antique vases. I hear a soft snore. It’s Mr. Greely, the home’s handyman. He’s asleep in a chair propped against the door to the library. I’m reminded of my old Grandpa George, resting after he tended his garden.

I look closer at Mr. Greely. He holds a mop in one hand. A bucket is at his

feet. A soft knock erupts from behind the door. Something I may have imagined,

or a noise manifested by an aged structure. Mr. Greely opens his eyes, looks at

me and then smiles. He closes his eyes and soon he’s snoring again.

feet. A soft knock erupts from behind the door. Something I may have imagined,

or a noise manifested by an aged structure. Mr. Greely opens his eyes, looks at

me and then smiles. He closes his eyes and soon he’s snoring again.

I leave him and I pad to the kitchen.

Davika, the cook, is busily stirring something in a pot on the stove. She’s a large woman, but her movements are light and swift. Her black hair is woven

in shimmering braids and adorned with red and blue beads. She’s wearing a bright orange shift. A black shawl covers her broad shoulders. Her

feet are bare and she’s singing. I’ve heard other girls say she has mental problems and used to live at the state

institution. She got the job here when she was released. Most of the girls

think she’s crazy as a loon.

in shimmering braids and adorned with red and blue beads. She’s wearing a bright orange shift. A black shawl covers her broad shoulders. Her

feet are bare and she’s singing. I’ve heard other girls say she has mental problems and used to live at the state

institution. She got the job here when she was released. Most of the girls

think she’s crazy as a loon.

I don’t sense craziness, just something mystical, something most others don’t understand.

I watch her pouring herbs from glass containers into the pot and then I slowly

back away, sensing that Davika is doing something secret.

back away, sensing that Davika is doing something secret.

She suddenly giggles and then turns. Her dark eyes sparkle. Fabric swooshes and

beads click. “Come here, girl. You’re hungry?” She pats her stomach. “You’re having the baby and Davika’s belly is twice as big as yours.” She lets out a hearty laugh.

beads click. “Come here, girl. You’re hungry?” She pats her stomach. “You’re having the baby and Davika’s belly is twice as big as yours.” She lets out a hearty laugh.

“There’s leftover roast in the fridge. Help yourself.” She turns and begins to stir and sing.

Devika pours liquid from a red clay bowl into the large pot. Whatever she’s cooking smells rich and flowery.

I open the fridge. Thick slices of pot roast lay on a dish. I grab a fork and

knife from the drawer by the dishwasher and devour food, not even bothering to

sit. I feel better now, but instead of returning to my room I watch Davika. She

reaches for a large container of salt.

knife from the drawer by the dishwasher and devour food, not even bothering to

sit. I feel better now, but instead of returning to my room I watch Davika. She

reaches for a large container of salt.

“I have to pour lots of salt into my brew.”

“Isn’t that bad?”

“Why would it be bad? Salt purifies.”

“My father told me the same thing.” An image of my father sprinkling salt on a makeshift altar drifts through my

mind. A sliver of light appears beside him and then another; bowed heads,

feathery wings and hands clasped in prayer.

mind. A sliver of light appears beside him and then another; bowed heads,

feathery wings and hands clasped in prayer.

“Did he now?” Davika turns and smiles at me. Silver flashes as she spins on her heels and

begins to stir rapidly.

begins to stir rapidly.

Other books

The Revolution by Ron Paul

Stepbrother Tormentor 1 of 2: A Steamy Romance by Brother, Stephanie

The Weight of Love by Perry, Jolene Betty

Three Ways to Wicked by Jodi Redford

The Ice Maiden by Edna Buchanan

Gastien Pt 1 by Caddy Rowland

The Most Human Human by Brian Christian

By Force of Instinct by Abigail Reynolds

The Concubine's Daughter by null

Karac: Kaldar Warriors #1 by T.J. Yelden