Darwin's Blade (47 page)

Authors: Dan Simmons

“Lawrence,” said Syd.

Dar raised his eyebrows slightly.

“You called him Lawrence,” said Syd. “Not Larry.”

“A name is important,” he said.

Syd smiled. “Let's take that walk, shall we?”

They had not walked more than ten paces before an explosion of noise behind them made them turn.

One of the smaller monkeys had miscalculated slightly and leapt for too small a branch, the branch had broken, and the little primate had fallen at least forty feet, using his hands and feet to grab at undersized branches and leaves every inch of the way down. The branches had all torn free but had softened his fall enough that he looked only shaken and embarrassed as he huddled on the concrete base of the monkey island and trembled, sitting on his haunches but curled almost into a fetal position. He was sucking his thumb for comfort. The sunlight glowed red through his ears, and his skin twitched.

Around him, more leaves and twigs continued to fall in a steady shower of debris. Above him, all of the other monkeys were chattering, screeching, gibberingâ¦It sounded like wild and mindless laughter. Other animals picked up the noise and roared, growled, coughed, and whinnied in unison until the entire zoo sounded like a giant echo chamber. Only Emma the elephant's infinitely sad trumpeting raised itself in lonely counterpoint to the chaos and chorus of hysterics.

Dar looked at Syd. She took his hand, smiled, shrugged, and shook her head.

Questions unanswered but some riddles solved, the two walked down the path from shade to sunlight and then back again.

The author would like to acknowledge the help and advice of Wayne A. Simmons and Trudy Simmons in researching this novel. Thanks also go to the Warner Springs gliderport for letting me test my theories on aerial combat in one of their high-performance sailplanes, to

The Accident Reconstruction Journal,

to the United States Marines' Scout Sniper School in Quantico, Virginia, and to Camp Pendleton in California. Acknowledgment should also be given to the writings of Stephen Pressfield on the Greek theories of

phobologia

âthe study of fear and its masteryâand to Jim Land, whose sniper instruction manual may be the definitive work on the topic. To the artist in the Acura division of the Honda Motor Corporation who assembled the engine of my Acura NSX by hand, I can say only

“D

Å

mo arigat

Å

gozaimasuâSh

Å«

ri o onegai dekimasu ka?”

All of the accidents investigated in

Darwin's Blade

are based upon real accident reconstruction files but each is a compositeâthe combination of several investigations into one reconstruction used for fictional purposes. My thanks go to all of the accident investigators and accident reconstruction experts whose professionalism, research, and bizarre sense of humor have illuminated this novel. Any accuracy or verisimilitude in this book is due to them; the mistakes, unfortunately, are the author's alone.

Dan Simmons is the award-winning author of several best-selling novels, including

Olympos

,

The Terror

,

Drood

, and

Black Hills

. He lives along the Front Range of Colorado and sometimes at Windwalker near Longs Peak on the Continental Divide.

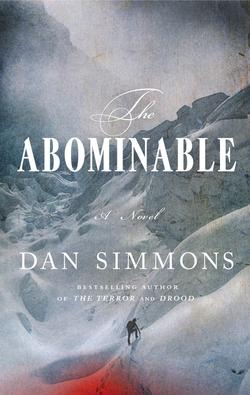

In October 2013, Little, Brown and Company will publish

The Abominable

.

Â

Â

Following is an excerpt from the novel's opening pages.

The summit of the Matterhorn offers very clear choices: a misstep to the left and you die in Italy; a wrong step to the right and you die in Switzerland.

T

he three of us learn about Mallory and Irvine's disappearance on Mount Everest while we are eating lunch on the summit of the Matterhorn.

It is a perfect day in late June of 1924, and the news lies folded in a three-day-old British newspaper that someone in the kitchen at the small inn at Breuil in Italy has wrapped around our cold beef and horseradish sandwiches on thick fresh bread. I've unwittingly carried this still-weightless newsâsoon to be a heavy stone in each of our chestsâto the summit of the Matterhorn in my rucksack, tucked alongside a goatskin of wine, two water bottles, three oranges, 100 feet of climbing rope, and a bulky salami. We do not immediately notice the paper or read the news that will change the day for us. We are too full of the summit and its views.

For six days we have done nothing but climb and re-climb the Matterhorn, always avoiding the summit for reasons known only to the Deacon.

On the first day up from Zermatt we explored the Hornli RidgeâWhymper's route in 1865âwhile avoiding the fixed ropes and cables that ran across the mountain's skin like so many scars. The next day we traversed to do the same on the Zmutt Ridge. On the third day, a long day, we traversed the mountain, again climbing from the Swiss side via the Hornli Ridge, crossing the friable north face just below the summit that the Deacon had forbidden to us, and then descending along the Italian Ridge, at twilight reaching our tents on the high green fields facing south toward Breuil.

I realized after the fifth day that we were following in the footsteps of those who'd made the Matterhorn so famedâthe determined artist-climber 25-year-old Edward Whymper and his ad hoc party of three Englishmen: the Reverend Charles Hudson (“the clergyman from the Crimea”); Reverend Hudson's 19-year-old protégé and novice climber Douglas Hadow; and the confident 18-year-old Lord Francis Douglas (who had just passed at the top of the British Army's examination list, some 500 marks ahead of the next closest of his 118 competitors), the son of the eighth Marquess of Queensberry and a neophyte climber who'd been coming to the Alps for two years. Along with Whymper's motley assortment of young British climbers with such wildly different levels of experience and ability were the three guides Whymper had hired: “Old Peter” Taugwalder (only 45, but considered an oldster), “Young Peter” Taugwalder (age 21), and the highly skilled Chamonix Guide, 35-year-old Michel Croz. In truth, they would have needed only Croz as a guide, but Whymper had earlier promised employment to the Taugwalders, and the English climber was always as good as his word, even when it made his climbing party unwieldy and two of the guides essentially redundant.

It was on the Italian Ridge that I realized the Deacon was introducing us to the courage and efforts of Whymper's friend, competitor, and former climbing partner Jean-Antoine Carrel. The difficult routes we were enjoying had been Carrel's.

We had our mountain tentsâWhymper tents, they were still called, since the famous Golden Age climber had designed them for use on this very mountainâpitched on the grassy fields above the lower glaciers on both sides of the mountain, and we arrived on one side or the other just before dusk every evening, often after dark, there to eat lightly, to talk softly by the small fire, and to sleep soundly for a few hours before rising to climb again.

We climbed the Matterhorn's Furggen Ridge but bypassed the impressive overhangs near the top. This was not a defeat. For one full day we explored approaches to that never-climbed overhang but decided that we had neither the equipment nor the skill to climb it direct. (The overhang would eventually be climbed by Alfredo Perino and Louis Carrel, known as “the little Carrel” in honor of his famous predecessor, and by Giacamo Chiara eighteen years later, in 1942.) Our modesty in not killing ourselves in an impossibleâgiven the equipment and techniques of 1924âattempt on the Furggen Ridge overhang reminded me at the time of how I had first met the 38-year-old Englishman Richard Davis Deacon and the 25-year-old Frenchman Jean-Claude Clairoux at the base of the unclimbed North Face of the Eigerâthe deadly Eigerwand. But that is a tale for another time.

The essence is that both Deaconâknown as “the Deacon” to many of his friends and climbing partnersâand Jean-Claude, just become a fully accredited Chamonix Guide, perhaps the most exclusive climbing fraternity in the world, had agreed to take me along for months of their winter, spring, and early summer climbing in the Alps. It was a greater gift than I had ever dreamed of. I'd enjoyed going to Harvard, but my education with the Deacon and Jean-Claudeâwhom I eventually came to call “J.C.” since he did not seem to mind the nicknameâfor those months was by far the most demanding and exhilarating educational experience of my life.

At least until the nightmare of Mount Everest. But I get far ahead of my tale.

On our last two days on the Matterhorn we made a partial ascent of the mountain by its treacherous west face, then rappelled down to work out routes and strategies on the truly treacherous north face, one of the Alps' final and most formidable unsolved problems. (Franz and Toni Schmid will climb it seven years later, after bivouacking one night on the face itself. They will ride their bicycles all the way from Munich to the mountain and, after their surprise ascent via the north face, will ride them home again.) For the three of us, it was a reconnaissance only.

This final day we had teased out routes on the seemingly unassailable “Zmutt Nose” overhanging the right part of the north face, then retreated, traversed to the Italian ridge, andâwhen the Deacon nodded his permission to climb the final 100 feetâfinally found ourselves here on the narrow summit on a perfect day in late June.

During our week on the Matterhorn we endured and climbed through downpours, sudden snowstorms, sleet, ice that turned rock to verglas, and high winds. On this final day, the weather on the summit is clear, calm, warm, and quiet. The winds are so docile that the Deacon is able to light his pipe after striking only a single match.

The top of the Matterhorn is a narrow ridge about a hundred yards long, if you wish to walk the distance between its lower, slightly broader “Italian summit” and its higher and narrowest point at the “Swiss summit.” In the past nine months or so, the Deacon and Jean-Claude have taught me that all good mountains give you clear choices. The summit of the Matterhorn offers very clear choices: a misstep to the left and you die in Italy; a wrong step to the right and you die in Switzerland.

The Italian side is a sheer rock face falling 4,000 feet to rocks and ridges that would stop a fall about halfway down the face, and the Swiss side falls away to a steep snow slope and rocky ridges hundreds of feet lower than the halfway mark, boulders and ridges that that might or might not stop a body's fall. There is enough snow here on the ridgeline itself for us to leave clear prints of our hobnailed boots.

The Matterhorn's summit ridge is not quite what excited journalists like to call “a knife-edge ridge.” Our boot prints in the snow along the actual ridge prove this. Had it been a knife-edge ridge, with snow, our boot prints would have been on

both sides,

since the smart way to traverse a true knife edge is to hobble slowly along like a ruptured duck, one leg on the west side of the narrow summit ridge, one on the east. A slip then will lead to bruised testicles but notâGod and fate willingâa 4,000-foot fall.

A slightly wider “knife-edge ridge” of snow, a vertical snow cornice, as it were, would have readied us for what Jean-Claude liked to call “a game of jump rope.” We'd probably be tied together on such a snowy knife edge, and if the climber directly ahead of or immediately behind you slips off one side, your immediate reaction (since there's little hope of belay from such a snowy knife edge)âan “immediate reaction” made instinctive only by many drillsâmust be to jump off the

opposite side

of the ridgeline, both of you now dangling over 4,000-foot or greater emptiness, in the desperate hope that (a) the rope does not break, dooming both of you, and (b)

your

weight will counter

his

weight in the fall.

It

does

work. We practiced it numerous times on a snowy knife-edge ridge on Mont Blanc. But it was a ridge where the punishment for failureâor a rope breakâwas a 50-foot slide to level snowfields, not a 4,000-foot drop.

I was 6 feet 2 inches tall and 220 pounds, so when I played “jump the rope” with poor Jean-Claude (5 feet 6 inches tall, 135 pounds), logic would dictate that he'd come flying up over the top of the snowy ridgeline like a hooked fish, sending both of us sliding out of control. But because Jean-Claude had the habit of carrying the heaviest pack of any of us (and was also the quickest and most skilled with his long ice axe), the balancing act usually worked, the heavily stressed hemp rope digging into the vertical snow cornice until it found either rock or solid ice.

But as I say, this long summit ridgeline of the Matterhorn is a wide French boulevard compared to knife-edge ridges: wide enough to walk upon, at least single file in some places, andâif you're very brave, supremely skilled, or totally stupidâto do so with your hands in your pockets and other things on your mind. The Deacon has been doing precisely this, pacing back and forth along the narrow line, pulling his old pipe from his jacket pocket and lighting it as he paces.

The Deacon, who could be taciturn to the point of silence for days, evidently feels expansive this late morning. Puffing on his pipe, he gestures for Jean-Claude and me to follow him in single file to the far side of the summit ridge, where we can look down on the Italian Ridge that saw the majority of the early attempts on the mountainâeven by Whymper, until he decided to use the seemingly more difficult (but in truth somewhat easier due to the angle of the huge slabs) Swiss Ridge.

“Carrel and his team were there,” says the Deacon and points to a line a third of the way down the narrow, rock-steepled ridge. “All those years of effort and Whymper ends up making the summit two or three hours ahead of his old friend and guide from Italy.”

He's talking, of course, about Whymper and his six fellow climbers' first summit ascent of the Matterhorn on July 14, 1865.

“Did not Whymper and Croz throw rocks down upon them?” asks Jean-Claude.

The Deacon looks at our French friend to see if he is joking. Both men smile.

The Deacon points to the sheer face on our left. “Whymper was mad to get Carrel's attention. He and Croz shouted and dropped rocks down the north faceânowhere near the ridge where the Italians were climbing, of course. But it must have sounded like cannon fire to Carrel and his team.”

All three of us gaze down as if we could see the heartbroken Italian guide and his companions staring up in shock and defeat.

“Carrel recognized his old client Whymper's white slop trousers,” says the Deacon. “Carrel thought he was an hour or less from the summitâhe'd already led his party past the worst obstacles of the ridgeâbut after he identified Whymper on the summit, he just turned around and led his party back down.” The Deacon sighs, inhales deeply from his pipe, and looks out over the mountains, valleys, meadows, and glaciers below us. “Carrel climbed the Matterhorn two or three days later, still from the Italian Ridge,” he says softly, almost speaking to himself now. “Establishing Italy's secondary provenance to the mountain. Even after the British chaps' clear victory.”

“Clear victory,

ouiâ¦

but so tragic,” says Jean-Claude.

We walk back to where we've stowed our rucksacks against some boulders along the north end of the narrow summit ridge. Jean-Claude and I begin unpacking our lunch. This is to be our last day on the Matterhorn, and it may be our last day climbing together for some timeâ¦perhaps forever, although I desperately hope not. I want nothing more than to spend the rest of my European

Wanderjahr

climbing in the Alps with these new friends, but the Deacon has some business in England soon, and J.C. has to return to his Chamonix Guide duties and an annual assembly of Chamonix Guides in that tradition-haunted Chamonix Valley, with its sacred brotherhood of the rope.

Shaking away any sad thoughts of endings or farewells, I pause in my unpacking to take in the view yet again. My eyes are hungrier than my belly.

There is not a single cloud in the sky. The Maritime Alps, 130 miles away, are clearly visible. The Ãcrins, first climbed by Whymper and the guide Croz, bulk blankly against the sky like the sides of some great white sow. Turning slightly to look north, I see the high peaks of the Oberland on the far side of the Rhône. To the west, Mont Blanc rules over all lesser peaks, its summit snows blazing with reflected sunlight so blinding that I have to squint. Swiveling slightly to face the east, I can see peak after peakâsome climbed by me during the last nine months with my new friends here, some waiting to be climbed, some never to be climbedâthe stuttered and irregular array of white pinnacles diminishing to a mere bumpy horizon wreathed in the haze of distance.

The Deacon and Jean-Claude are eating their sandwiches and sipping water. I snap myself out of my sightseeing and romantic reverie and begin to eat. The cold roast beef is delicious, the bread rich with a crust that makes me work at chewing. The horseradish makes my eyes water until Mont Blanc becomes even more of a white blur.

Looking south, I celebrate the view that Whymper wrote about in his classic book

Scrambles Amongst the Alps in the Years 1860â1869.

I can clearly recall the words I read only the evening before, read by candlelight in my tent above Breuil, the words describing Edward Whymper's first view from the summit of the Matterhorn on July 14, 1865

,

this

view that I'm devouring in late June of 1924: