Darwin's Island (7 page)

Authors: Steve Jones

However it began, language makes us what we are. The ability to speak is coded for on the left side of the brain and plenty of primates have a brain almost as lopsided as our own. Even so, chimp tongues fill their mouths while ours are dainty in comparison. The human tongue has retreated down the throat. The language of Shakespeare is a complex set of sounds made as the space above the larynx flexes and bends. The anatomical changes leave evidence in the shape of the skull. Neanderthals had chimp-like mouths and could do little more than grunt. The first skull capable of speech emerged no more than fifty thousand years ago - not long before the explosion of technology that led to the modern world.

One British child in twenty has some form of speech disorder. A certain rare inborn abnormality makes it impossible for those who inherit it to cope with grammar. Baby mice with the same damaged gene make fewer squeaks than usual when removed from their mothers, and people with a version impaired in a different way are at risk of schizophrenia; of, like Saint Joan, hearing voices that are not there. The normal version found in humans differs in two of its amino acids from that in all other primates. It is foolish to speak of a gene for language but if the transition from animal to human turned on speech it may have involved rather few molecular changes. The situation is confused by the discovery that Neanderthals have the human version of the gene, which must hence date back to our inarticulate joint ancestor.

Wherever they came from, words are the raw material of a new kind of genetics, in which information passes through mouths and ears as well as through eggs and sperm. It moved us on from our status as a rare East African ape to the most abundant of all mammals. Ideas, not genes, make us what we are. Our DNA is not very different from those of our kin, but what we do - or say - with it has formed our fate.

Even so, the famous ‘indelible stamp’ is without doubt imprinted into the human frame. Modern biology shows that chimpanzees are even more like us than Charles Darwin imagined - but in no more than the most literal way. The strengths and the limitations of his ideas in deciphering what makes us human have become ever clearer as knowledge advances. His theory is powerful indeed but enthusiasts need to be reminded where its power comes to an end.

In 1926, the Soviet government sent an expedition to Africa. It was directed by Ilya Ivanovich Ivanov, famous for his work on the hybridisation of horses and zebras by artificial insemination. The Politburo hoped to do the same with men and apes, for the experiment would be ‘a decisive blow to religious teachings, and may be aptly used in our propaganda and in our struggle for the liberation of working people from the power of the Church’. In Guinea, Ivanov obtained sperm from an anonymous African and inseminated three chimps - but none became pregnant. He then planned to fertilise women with chimpanzee sperm, but was not allowed to do so. Back in Russia he set out to do the same with a male orang-utan and a woman who had written that ‘With my private life in ruins, I don’t see any sense in my further existence . . . But when I think that I could do a service for science, I feel enough courage to contact you. I beg you, don’t refuse me . . . I ask you to accept me for the experiment.’ The orang, alas, died before its moment of glory and Ivanov was arrested and exiled to Kazakhstan, where he, too, met a childless end.

Americans anxious to stop research in human genetics once attempted to patent the idea of a human-chimp hybrid in order to whip up protest. The application was denied on the equivocal grounds that the US constitution does not allow the ownership of human beings (whether the cross-breed would have that status was not discussed). Artificial fertilisation of chimpanzee egg with a man’s sperm may now be feasible (although claims to have produced a ‘humanzee’ are fraudulent) but is universally seen as beyond the pale. The problem is not one of biology, but of what it means to be human. A hybrid between a chimp and

Homo sapiens

makes too ready an equation between our apish bodies and our immortal minds.

Homo sapiens

makes too ready an equation between our apish bodies and our immortal minds.

Charles Darwin was well aware of the limits of his own theory. As he points out in the famous last sentence of

The Descent of Man

, men and women possess noble qualities, sympathy for the debased, benevolence to the humblest and an intellect which penetrates the solar system. All that does not change the fact that in our bodily frames, most of all when reduced to chemical fragments, we bear the indestructible mark of our humble ancestry.

The Descent of Man

, men and women possess noble qualities, sympathy for the debased, benevolence to the humblest and an intellect which penetrates the solar system. All that does not change the fact that in our bodily frames, most of all when reduced to chemical fragments, we bear the indestructible mark of our humble ancestry.

Some people despise his science as a result, because it appears to destroy man’s special place in nature, but they fail to understand what evolution is all about. Biology, in its proof of our kinship with chimpanzees, underlines its irrelevance to ourselves. The double helix does not diminish

Homo sapiens

but sets him apart on a mental and moral peak of his own. The theory of evolution does not render us less human than we were before. Instead the insight it provides into man’s place in nature has made us far more so than we ever realised. A century and a half after Queen Victoria’s disagreeable visit to Jenny the orang-utan, I gave a talk at London Zoo which pointed this out - and most of the apes agreed.

Homo sapiens

but sets him apart on a mental and moral peak of his own. The theory of evolution does not render us less human than we were before. Instead the insight it provides into man’s place in nature has made us far more so than we ever realised. A century and a half after Queen Victoria’s disagreeable visit to Jenny the orang-utan, I gave a talk at London Zoo which pointed this out - and most of the apes agreed.

CHAPTER II

THE GREEN TYRANNOSAURS

Soaring above southern Venezuela is a hidden landscape: the sandstone plateau of Mount Roraima, an inaccessible peak that is most of the time shrouded in mist. Arthur Conan Doyle used the place, or one very like it, as the location for his 1912 book

The Lost World

, a tale set in a land of evolutionary imagination, a place of dinosaurs, ape-men and primitive humans, ready to be explored by the irascible Professor Challenger. It was a fearsome spot but the bearded Englishman lambasted the lizards and saved the savages, as any Edwardian reader would expect.

The Lost World

, a tale set in a land of evolutionary imagination, a place of dinosaurs, ape-men and primitive humans, ready to be explored by the irascible Professor Challenger. It was a fearsome spot but the bearded Englishman lambasted the lizards and saved the savages, as any Edwardian reader would expect.

Conan Doyle was born in the year of

The Origin

. By his fifty-third birthday, the theory of evolution had become so widely accepted that a literary hack could use it as the centrepiece of a work of fiction. Conan Doyle, who had read the reports of the British explorer who discovered the unique island in the sky, seized the chance and his book sold hundreds of thousands of copies to a well-primed public.

The Origin

. By his fifty-third birthday, the theory of evolution had become so widely accepted that a literary hack could use it as the centrepiece of a work of fiction. Conan Doyle, who had read the reports of the British explorer who discovered the unique island in the sky, seized the chance and his book sold hundreds of thousands of copies to a well-primed public.

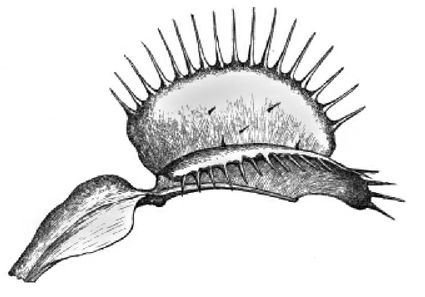

In reality the dinosaurs had gone from Roraima millions of years before and the local ‘savages’ never made it to the top. Even so, its remote summit is a genuine lost world, not of giant anthropophagous lizards or man-eating apes but of unobtrusive plants with the same dietary habits. Those green carnivores turn for food not to human flesh, but to insects. They must do so or starve.

Their habit is widespread. Almost six hundred insect-eating species, from all over the world, and from a wide variety of groups, have now been discovered. Their way of life has evolved on many occasions, and the tactics used to trap and digest prey are varied indeed. Separate lineages, from quite different places in the evolutionary tree, have taken up an identical diet and have come to the same solutions to find, digest and absorb their food. Charles Darwin had used such convergent evolution, as the process is known, as evidence for natural selection in

The Origin of Species.

The similarity of certain Australian marsupials to true mammals elsewhere in the world, or of wings in birds and bats, was, he saw, powerful proof of its action. Unrelated creatures faced with the same challenges adopt structures and habits that look similar but have different roots. As he pointed out, life can reach the same end through quite different pathways: ‘in nearly the same way as two men have sometimes independently hit on the very same invention, so natural selection, working for the good of each being and taking advantage of analogous variations, has sometimes modified in very nearly the same manner two parts in two organic beings, which owe but little of their structure in common to inheritance from the same ancestor’.

The Origin of Species.

The similarity of certain Australian marsupials to true mammals elsewhere in the world, or of wings in birds and bats, was, he saw, powerful proof of its action. Unrelated creatures faced with the same challenges adopt structures and habits that look similar but have different roots. As he pointed out, life can reach the same end through quite different pathways: ‘in nearly the same way as two men have sometimes independently hit on the very same invention, so natural selection, working for the good of each being and taking advantage of analogous variations, has sometimes modified in very nearly the same manner two parts in two organic beings, which owe but little of their structure in common to inheritance from the same ancestor’.

Now we know many such examples - flight not just in birds and bats but in squids, fish, dinosaurs, flying squirrels and the marsupial sugar-glider of Australia (not to speak of the flying snake whose flattened body allows it to glide for many metres from a tall tree). We ourselves are not immune to convergence, for plenty of creatures have lost their hair, grown their brains, or even - as in the meerkats of Africa, who instruct their infants how to eat poisonous insects - stood upright and gained some simulacrum of the ability to educate.

Evolution in response to a common challenge has been so effective that certain creatures once assumed to be close relatives because they are so much alike in form are in fact not real kin: the vultures of the Old and New World, similar as they appear, do not have a recent common ancestor, for the former are eagles and the latter storks. Anteaters and aardvarks, lions and tigers, moles and mole-rats - all hide a bastard ancestry beneath their shared appearance. The process goes further. On Roraima itself, for unknown reasons, melanism is rife among unrelated organisms, and the rocks harbour black lizards, black frogs and black butterflies. The mutation responsible for black melanin pigment is the same, or almost so, in zebrafish, people, mice, bears, geese and Arctic skuas (and perhaps even in lizards and frogs), and has been picked up by natural selection in each. Within the cell, too, shared evolutionary pressures have produced enzymes with distinct histories that have settled on an almost identical DNA sequence in the active parts of the molecule. On a more intimate scale, the complicated chemical used as a sexual scent by certain species of butterfly also does the same job for elephants (which is riskier for one partner in the relationship than for the other). Evolution towards a common plan is just as rife among plants. The cactuses of the Americas - spiny, thick-skinned and globular - resemble the Euphorbias of South Africa, but have no more than a distant affinity to them.

Just after the publication of

The Origin

, Darwin began to work on a botanical lifestyle that, as he soon found, drags a great diversity of unrelated species into a shared set of habits. His interest began in 1860, when he visited Hartfield in Sussex, on the edge of Ashdown Forest, the home of his sister-in-law Sarah Elizabeth Wedgwood (and later the birthplace of Winnie the Pooh). There he saw thousands of sundews - small clumped plants, with a sticky surface that traps insects. Some had as many as thirteen victims on a single leaf. Most of the prey consisted of small flies, but some victims were as large as a butterfly and he was told that the traps could even catch dragonflies. As so many sundews were present, the numbers of insects slaughtered must, he calculated, be prodigious. Each leaf had scores of glands held upright on fine hairs. They exuded shiny globules of liquid even on dry days and entangled any small creature foolish enough to land upon them. The sundew, he found, had feeble roots - evidence that most of its nutrition did indeed come from its gruesome way of life. He brought some specimens back to his greenhouse and began to explore how they did their job. It was the first step in a decade of work that produced a powerful vindication of his claim in

The Origin

that natural selection could, starting from different places, end up with much the same result.

The Origin

, Darwin began to work on a botanical lifestyle that, as he soon found, drags a great diversity of unrelated species into a shared set of habits. His interest began in 1860, when he visited Hartfield in Sussex, on the edge of Ashdown Forest, the home of his sister-in-law Sarah Elizabeth Wedgwood (and later the birthplace of Winnie the Pooh). There he saw thousands of sundews - small clumped plants, with a sticky surface that traps insects. Some had as many as thirteen victims on a single leaf. Most of the prey consisted of small flies, but some victims were as large as a butterfly and he was told that the traps could even catch dragonflies. As so many sundews were present, the numbers of insects slaughtered must, he calculated, be prodigious. Each leaf had scores of glands held upright on fine hairs. They exuded shiny globules of liquid even on dry days and entangled any small creature foolish enough to land upon them. The sundew, he found, had feeble roots - evidence that most of its nutrition did indeed come from its gruesome way of life. He brought some specimens back to his greenhouse and began to explore how they did their job. It was the first step in a decade of work that produced a powerful vindication of his claim in

The Origin

that natural selection could, starting from different places, end up with much the same result.

In 1875, he published a book,

Insectivorous Plants

, on the subject. It deals not just with sundews but with a variety of such creatures from across the world, some from the area of Roraima itself. Darwin soon found many similarities among the various species that have taken up the habit. A closer look showed that many of their adaptations are also present in the other major kingdom of life. Emma noted in her diary when he was at work on a certain insectivore that ‘I suppose he hopes to end in proving it to be an animal.’ Her husband was so astonished by such parallels that he wrote to a friend that ‘I am frightened and astounded at my results.’ The aesthete John Ruskin said, in contrast, that ‘with these obscene processes and prurient apparitions the gentle and happy scholar of flowers has nothing whatever to do. I am amazed and saddened, more than I can care to say, by finding how much that is abominable may be discovered by an ill-taught curiosity.’ Darwin’s curiosity, ill-taught or not, added another plank to his evolutionary edifice.

Insectivorous Plants

, on the subject. It deals not just with sundews but with a variety of such creatures from across the world, some from the area of Roraima itself. Darwin soon found many similarities among the various species that have taken up the habit. A closer look showed that many of their adaptations are also present in the other major kingdom of life. Emma noted in her diary when he was at work on a certain insectivore that ‘I suppose he hopes to end in proving it to be an animal.’ Her husband was so astonished by such parallels that he wrote to a friend that ‘I am frightened and astounded at my results.’ The aesthete John Ruskin said, in contrast, that ‘with these obscene processes and prurient apparitions the gentle and happy scholar of flowers has nothing whatever to do. I am amazed and saddened, more than I can care to say, by finding how much that is abominable may be discovered by an ill-taught curiosity.’ Darwin’s curiosity, ill-taught or not, added another plank to his evolutionary edifice.

Roraima and the flat islands of rock around it are ancient indeed. Its sandstone peak - once part of a wide and barren plain, most of it now eroded away - is almost two billion years old. In the context of its immense history the terrible lizards went not long ago and the humans clustered around its base arrived in an evolutionary yesterday.

Its unique vegetation has been on its rain-soaked flanks for longer than either. The plants have seen the slow passage of time and have changed to match. A third of them evolved upon the mountain’s lonely rocks and are found only there. Their native land is a hungry place. Constant downpours eat at the soil and strip what remains of nutriments, which are tipped down some of the highest waterfalls in the world. Worst of all, the rain washes away the nitrogen that every tree, shrub or flower needs to grow. Sandstone peaks, deserts, dunes, bogs, pine forests, Mediterranean scrublands and more - all are short of that element and each, distinct as it looks, and different as its inhabitants might be, has evolved a set of inhabitants whose battle for existence is focused, in a variety of ways, on the need to find it. The struggle for nitrogen shows - even better than the multitude of ways in which life has taken to the skies - how natural selection can reach the same end with different means in creatures from quite separate parts of the biological universe. Plants, animals, bacteria and fungi are all drawn together in their shared hunger for the element and all have become entangled with each other in the struggle to find it.

Other books

Arabella by Herries, Anne

Bake Sale Murder by Leslie Meier

No Easy Choices (A New Adult Romance) by Cade, Trista

The War That Came Early: Coup d'Etat by Harry Turtledove

Beach Glass by Colón, Suzan

Let Me Go by Chelsea Cain

What Came After by Sam Winston

Love on a Deadline by Kathryn Springer

Stones From the River by Ursula Hegi

The Main Death and This King Business by Dashiell Hammett