David Jason: My Life (6 page)

Read David Jason: My Life Online

Authors: David Jason

Tags: #Biography & Autobiography, #Entertainment & Performing Arts, #Performing Arts, #Television, #General

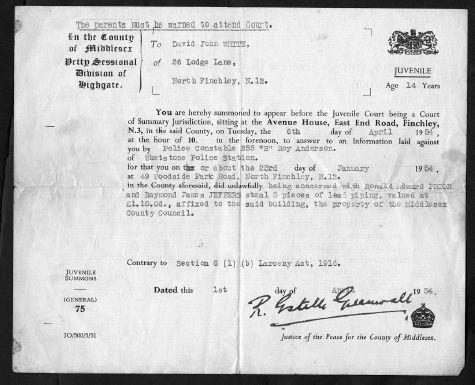

Our defence, m’lud: the resale value of the said and formerly affixed piping was of no interest to us, the juveniles in question (Masters White, Prior, Jeffers), being not so much unlawfully concerned with the making of a quick ten bob on the sly, but rather with the melting down of the aforementioned lead and the forming it thereafter into soldiers to play with, in all innocence, as young boys, if it so please the court.

Was that true? Both the passage of time and due respect for the processes of the law insist that we draw a veil over this element of the proceedings. Let us merely note, before moving swiftly on, that, after a morning in court with a very tidy head of hair, a very well-knotted tie and a decidedly less than impressed father, I was ‘discharged, subject to the condition that he commits no offence during the period of twelve months next ensuing’.

So, was I, at this point in my life and about to leave school, on the slippery slope towards a life of petty crime? Or was I just a north London lad with a little bit too much time on his hands who needed occupying?

Either way, it didn’t matter. I had found something to keep me off the streets and out of mischief. I had a new hobby.

CHAPTER THREE

Going Incognito. Adventures in electricity. Further lasting scars. And why you should never go in the lift shaft of an incomplete block of flats.

IMMEDIATELY AFTER THE

historic victory of

Wayside War

in the hotly contested East Finchley Drama Festival of 1954, my mate Micky Weedon and I were standing around, soaking up the glory and generally feeling rather smug about ourselves, when a man in a cravat came up. His name was Doug Weatherhead and he was the director of one of the other plays that we had defeated in the final. He offered his congratulations and said a few kind words, roughly amounting to ‘Darlings, you were marvellous’. And then he asked us if we would like to join his amateur theatre club.

This would have been the Incognito Theatre Group, based not far from Finchley in Friern Barnet, for which this bloke Doug ran the junior section. And, clearly, his offer was of no interest to us whatsoever. Less than no interest. Do amateur dramatics outside school – in your own time? This man must have taken us for fools. Micky and I smilingly declined.

‘Well, that’s a pity,’ Doug said. ‘We could do with a couple of boys. We’ve got about twenty girls and no males so it’s getting hard to find plays we can cast.’

Imagine here, if you will, a short silence in which the sudden whirring of cogs in the minds of two fourteen-year-old boys is almost audible. Imagine too, perhaps, the sight of those two fourteen-year-old boys exchanging a look of dawning comprehension.

An abundance of girls? A shortage of boys?

‘What time does this group of yours meet?’ I asked.

A week later I became an active member of the Incognito Theatre Group and stayed that way for the best part of eleven years until I became a professional.

Would amateur theatre have lured my boyhood self eventually, of its own accord, without this additional ‘abundant girls’ aspect? Perhaps, with enough encouragement and enough prodding from external sources. But what I can say for sure is that Doug Weatherhead had caught me and Micky at a very vulnerable moment. By this point in our lives, puberty had begun to wreak its steamy havoc. Yet, of course, in those days, in 1950s Britain, puberty had an extraordinary amount of difficulty wreaking anything at all. Even on into my later teens, sexual activity was an exotic, remote and highly tentative thing. Girls, assuming you had access to them, tended to be extremely reluctant to help your puberty along its way, and the opportunity to get even as far as ‘first base’ seemed like the rarest of blessings.

Some of us Lodge Laners in those sensitive, budding years were fortunate enough to be smiled upon by a neighbourhood girl who, in and around the bomb site playground and just occasionally down the side of the Salvation Army Hall, would uncomplicatedly enable curious male acquaintances to touch her breasts. However, lest you get the impression that this was a woman of woefully loose principles, let me make clear that you could only ever feel those cherished parts a) briefly and b) through the thick insulation supplied by her jumper and bra. One’s gratitude was boundless, of course. But in such a context, the idea of eventually consummating a relationship and having

something that we had heard called ‘sex’ was a dream, entirely fantastical – about as connected with reality in our minds as an episode of the Dan Dare comic strip in

The Eagle

.

The morals of the day, certainly in working-class communities, had set themselves firmly against sexual experiment, and certainly against experimental intercourse. A terrible stigma was attached to getting pregnant outside marriage, and that stigma extended also to children born out of wedlock. Unwedded conception spelled nothing less than social ruin, for you and your family, not to mention the poor soul that you brought into the world. Girls had to bear the most formidable brunt of that, of course, so if they came across as cautious, or even prim and proper, who could blame them? Boys, for their part, trembled in the knowledge that, nine times out of ten, a slip-up would mean marriage. And marriage was forever, and forever was a very long time.

However, the idea of using a condom was fraught with complication to the point of impossibility. There was the difficulty of acquiring such a thing, for a start, which would require a staggering act of face-to-face boldness in a chemist or a barbershop. And, in any case, they were joke objects – invented, so it seemed to us, not for the serious purposes of birth control, but entirely so that boys would have something about which to make smutty, but somehow ceaselessly amusing, jokes involving the word ‘johnny’. Encounters were kept to petting – in various weights up as far as ‘heavy’, if you were lucky, which you probably weren’t – and no further. Small wonder that a brief touch of entirely wool-encased and cotton-packed breast was something both prized and glorious. Meanwhile, if amateur dramatics could guarantee to put Micky Weedon and me in a room where girls, with all their distant promise, regularly abounded – well, then Micky Weedon and I were automatically in favour of amateur dramatics, and all power to its elbow.

And so it came to pass that, on a Monday evening in the

early summer of 1954, Micky and I leaned our bikes up against the wall of the former lemonade factory which was the headquarters of the Incognito Theatre Group and, rigid with self-consciousness, shuffled to a position narrowly inside the door. Just as Doug had forewarned, the gathering that met our eyes in that room was almost exclusively female. Did we therefore immediately glide, swan-like, into the centre of the throng and begin to turn on our nonchalant and yet somehow irresistible charm? No. We clung together and refused to let one another out of each other’s sight for the rest of the evening.

That first Monday, I don’t think we took any active part in the proceedings at all – just watched as Doug put the others through their paces, getting them up onstage in little groups and cooking up scenes in which they could improvise. Slowly, though, over the course of the following weeks, Micky and I thawed enough to get involved. And, clearly, even setting aside purely demographic considerations, we couldn’t have been more fortunate in where we had landed up. The Incognito Group had been running since 1938 and had the exceptional advantage of operating out of its own theatre. That small, red-brick factory, set back from Holly Park Road, had been acquired after the Second World War, and had then been renovated and fitted out with rows of seating bought from a bombed cinema to make a small but perfectly serviceable auditorium. OK, the facilities might not have been West End standard – the upstairs dressing rooms were fairly dingy and what the theatre offered by way of lavatory facilities, to actors and audience alike, was a set of Elsan portable chemical toilets down an alleyway at the side of the building. Inconveniently, there were no lights out there so, on play nights, ladies who desired to powder their noses (such as my mother and my aunts and various family friends, who became unfailing patrons of any Incognito production that I was involved in) were offered a torch to guide them on their way.

Still, the priceless advantage of having this dedicated space, rather than sharing a hall or a public room somewhere, as most amateur groups had to, was that sets for a production could be built and left up for the run of the play, rather than dismantled every night or partly packed up so that the local Mothers’ Union, or whoever, could have the run of the place the following morning. It gave the Incognitos a bit of an edge.

The other thing the group was clearly blessed with was Doug Weatherhead, a man who was, I came to realise, tirelessly dedicated to the organisation and to the cause of amateur theatre in general, and someone to whom I would end up owing an awful lot. In due course, Doug coaxed me onto the stage and began to set me those little improvisations. ‘I want you to come up with Janet and Rita,’ he would say, ‘and pretend that you are the husband of one and the boyfriend of the other. How are you going to cope with that?’

How indeed? But Doug was an excellent coach, who would always say afterwards, ‘That’s very good, but what about the possibility of this? Or what about considering it this other way?’ What he was doing was building our confidence to stand up in front of the rest of the group and let go a little.

Fat chance of that with me, though, in the beginning. I found those initial improvisational set-ups purgatory. They didn’t just make me uncomfortable: they made me want to shrivel up and post myself down a crack in the floorboards. But when Doug eventually handed out some sheets of paper and we started to run through a bit of a play, things were totally different. Then I had something to grab hold of and I felt less exposed. I discovered that if I could add the confidence I had found as a freelance impressionist in the school playground to some written lines, then I was away.

Pretty soon after this, I went to see the company compete at a local drama festival. Another group there put on a play called

Dark of the Moon

– a strange, alluring piece about witchcraft and superstition and all manner of weird goings-on in the Appalachian Mountains. I remember feeling enthralled, loving the oddness of it. The Incogs won a prize that time, which was quite inspiring, too. My own Incog debut came when Doug put me in a one-act play set in the Far East; as I recall, I played opposite a girl called Rita Chappel, but otherwise memory has drawn a gauzy veil over this production’s majesty and the sensation it no doubt caused across the theatrical world. However, I more sharply remember doing another early show – a one-acter for a drama festival, a piece about crooks taking over a ladies’ hairdressing salon. The crooks in question had hopped into a hairdresser’s to evade the police and then had to pretend they were running the place. As one of the crims caught up in this farrago, it was beholden upon me at one point to call out, primly, ‘Louise – the telephone please!’ Comedy gold, I’m sure – but an uncommon foray into that area for the Incognito Players.

Indeed (and this might seem odd, given what I would eventually go on to specialise in), comedy was rarely on the bill for the Incogs. Where possible the group liked to go in for pieces of serious drama – with the emphasis on serious. In 1959, for example, we treated Friern Barnet to a production of

Easter

by August Strindberg. Two hours of furrow-browed Swedish angst in a theatre with an outdoor toilet … it doesn’t really get much more cerebral than that, drama-wise. I’m not sure how much of that play I understood at the time, at the age of nineteen, and I’m not sure how much of it I understand now, to be perfectly honest. But I can certainly tell you that at no point did this production require anyone to go for a big belly laugh by falling through the open flap of a pub bar. Permit me to reproduce the introductory note from the programme for the occasion (handwritten in ink on a sheet of plain A4 and xeroxed, as was the way):

The play is set in Lund, a small provincial town in Sweden. It was in this town that Strindberg spent the winter of 1896 recuperating after his mental breakdown. Here he watched the spring return and was moved as never before by the sufferings of Holy Week.

And a happy Easter to you, too.

Even closer to the cutting edge, I played Cliff Lewis, the Welsh lodger, in an Incognito production of John Osborne’s

Look Back in Anger

, put on soon after the play’s professional debut at the Royal Court Theatre in 1956 – where it had caused no little shock and horror in certain quarters for its unadorned portrayal of working-class life. That was quite a hot item for an amateur group to dare to pick up on so quickly, but the Incogs knew very little fear in these areas. We also put on Osborne’s

Epitaph for George Dillon

. We did Tennessee Williams’s

The Glass Menagerie

, too, and I also remember playing a shell-shocked soldier in the trenches of the First World War – no bag of laughs. And in an adaptation of the biblical story of Noah, I played Ham, the bad ’un among Noah’s sons. Again – not much in the way of pratfalls here.