Dead Man's Gold and Other Stories (5 page)

Read Dead Man's Gold and Other Stories Online

Authors: Paul Yee

The Brothers

IN CHINA THERE

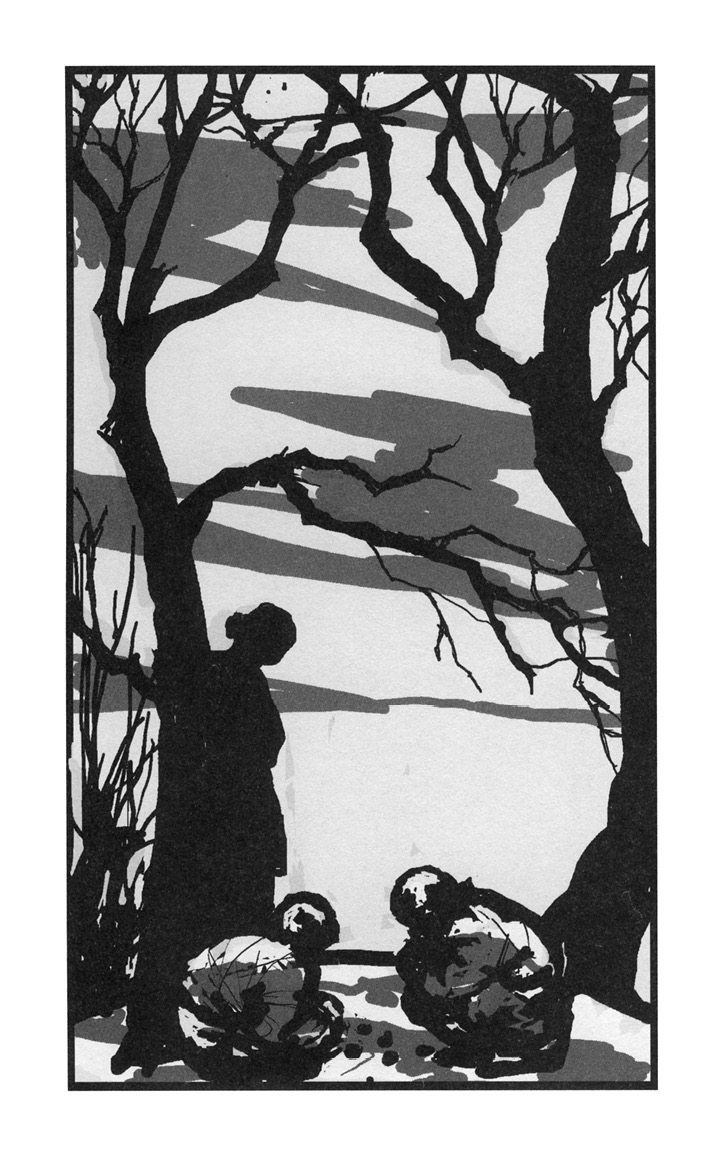

once lived a poor widow who had two young sons but neither land nor family to support her. Though frail in health, she solicited odd jobs from neighbors, crouched in their paddy fields during planting and harvesting, and sewed late into the night. And she relied on the kindness of clan members and fellow villagers. Without them, she would have had to beg for food and coins from strangers in the market town. She tried to raise honest boys, but villagers told tales about the younger son, Ping, that made her sigh with sorrow.

They said whenever Ping was given a dish of food to take home, he gulped down the choice pieces before his mother and brother ever saw the meal. When he ran small errands for neighbors, he kept the change by claiming the cash had been lost.

When market stall-keepers accused him of stealing, his mother beat him with bamboo, but he grit his teeth and showed no remorse. Within days, she would hear fresh reports of thefts.

Whenever Ping landed in trouble, his mother scolded the older brother.

“Where were you, you stupid thing?”

“Why weren't you watching him?”

“Can't you keep him out of trouble?”

Shek was two years older and always volunteered to do chores for the neighbors in return for a few coins. But the villagers told him, “You're a good boy, but you should learn to talk fast like your brother. Sometimes he's naughty, but he's always quick and clever. He can sweet-talk his way out of any hole.”

Shek tried to follow Ping everywhere. He couldn't stop all the mischief because his younger brother always managed to evade him. One day, he saw Ping topple the bamboo scaffolding as workers constructed a towering arch, causing one man to fall and break his leg. But he told no one, not wanting to bring more grief to his mother.

The two boys grew up. But young men who could neither read nor write had no future. They searched nearby towns and ports for work but returned home dusty and penniless. Finally, their mother decided to send them to Gold Mountain, desperately borrowing from money lenders and kinsmen to pay the passage.

At departure time, she reached out and seized Ping. “I can't teach you about honesty any more,” she cried. “In the New World, you will have to follow the laws of the land. When you return to the village, come back as a good man. In the meantime, send money so I can hold my head high.”

Ping shrugged her off. He wasn't pleased about leaving home and fending for himself. His mother had always washed his clothes and put food on the table.

Then she gave Shek a single piece of advice. “Watch over your brother. It's your duty.”

When they arrived in the New World, the brothers split up. Shek joined a salmon-canning crew up north while Ping washed restaurant dishes in the city. Then Shek yanked planks off the chain at a sawmill in the coastal forests while Ping butchered hogs in the interior. Ping enjoyed the freedom of being away from his brother, but his slack work habits often got him fired from jobs, and then he would have to ask Shek to send him money.

Finally, the two ended up together in the city, where Shek borrowed money to buy a farm by the river. The farmhouse was built of logs held in place by plaster and mud, but the soil was dark, soft and fragrant. Shek joyfully flung handfuls of dirt into the air.

“I own land!” he exulted. “I own something that lasts forever.” He said to his brother, “Come work with me. Everyone has to buy food, because everyone has to eat. We'll grow rich together.”

Ping shook his head. He sneered at the lopsided barn, beat-up truck and battered equipment his brother now owned. The rusty tin roof sagged and leaked, and there was no running water in the house.

“This place stinks of mud and dung,” he cried. “I didn't come to Gold Mountain to roll in the dirt like a hog.”

He fled downtown and found a job in a laundry. There, great iron boilers roared to heat water and dry the wash. As he stirred sheets and shirts in vats of detergent, he would sweat all day even when it rained or snowed outside. Whenever his boss went to the front counter to serve customers, Ping sneaked out the back door to smoke cigarettes. When he was in a rush to leave, he would rinse the wash only once instead of twice. If customers complained, he always denied any wrongdoing.

As usual, whenever he had spare cash, he went gambling. He played fan-tan, mah-jongg and dominoes. His friends played for high stakes, and money slipped through his fingers like sand. He never sent a penny home because Shek handled the remittances.

Three or four times a year, Shek visited a Chinatown company and handed over an amount to be forwarded to China. Then he went to a letter-writer to have a message written, telling his mother to go to the company's branch office in the market town to retrieve the money. To relieve her worries, Shek always claimed the funds were from the work efforts of both brothers.

Once, after the police raided a game-hall and arrested thirty gamblers, Ping slept on the concrete floor of the jail for three nights before Shek bailed him out. If Ping was lucky enough to win at the tables, he summoned all his friends to feast on bird's nest soup, sharks fin and abalone. Song-girls entertained them, guests danced to the gramophone, and the banquet lasted all night. But he never invited Shek, who frowned on such carefree spending.

A few years later, the Great Depression descended. Factories and mills closed, and workers across the contiÂnent lost their jobs. Long lines formed at soup kitchens, and homeless men slept in shantytowns under bridges. Many Chinese booked passage back to the homeland.

When Ping's laundry went bankrupt, he had no choice but to go and live with Shek, who was glad to get a helper and have his brother nearby.

Ping soon discovered the rigors of farm work. When he met his buddies in Chinatown, he complained at length.

“I start at daybreak, work until dark, swallow some rice, and then sleep a few hours until it's barely bright enough to see my hands in front of me. Chores are always waiting. A second seeding has to go in, seedlings need to be transplanted, or crops must be harvested before insects eat everything. I can never scrub myself clean, my fingernails are permanently black, and my back aches all the time. I am nothing but food for mosquitoes to feast on.”

He hated the farm a hundred times more than the laundry. The outhouse was a long walk away, and when it rained, his bed became soggy. He looked for ways out, but Shek did not pay him wages, so there was no opportunity to win at gambling or to buy a train ticket out of town.

So he decided the only way to get money was by improving the farms income. He challenged the way his brother grew many different vegetables. Shek had reasoned that if carrots didn't sell, then the lettuce would. And if the radish crop turned brown and mushy, then tomatoes would reduce the loss.

Ping noticed that potatoes always sold well, and argued the farm should grow nothing but that one crop.

“It's too much work with different vegetables,” he insisted. “Too many plantings, too many diseases, too many things to remember and worry about. With potatoes, you plant them and dig them up, bag them, ship them out, and you are all done. And we can get rich, since the whites eat them every day.”

Shek's brow furrowed as he thought about the proposition. Every day, Ping would reframe his arguments and add new information.

“Look at Chung Chuck! He grows only potatoes and has built a new farmhouse and owns three trucks. Even white farmers and politicians call him the King of Potatoes.”

“Did you hear? The wholesalers raised the prices paid to potato farmers by five cents a sack! It's the third raise this season.”

“Have you seen this? The Marketing Board is giving every housewife in town a free cookbook with a hundred recipes for cooking potatoes! Sales of potatoes are sure to go up.”

Gradually, Shek gave in to his brothers position, so next spring, they seeded the fields with only potatoes. There was a bit less work that summer, and a good harvest followed. With the extra income, Ping had money to play with, and Shek sent extra funds home and paid down his debt.

Then Ping had another idea. “You should sell the farm! That way, we can both return home and retire in comfort. We wont ever have to work again!”

“No!” cried Shek. “I'll never find a piece of land so fertile and large in China.”

Ping knew his brother was right, because the ancient soil back home had supported crops over many hundreds of years. And the families owning tracts of good land would never sell, no matter what amount was offered. But that didn't stop Ping from insisting on leaving.

The following spring, when the tax inspector visited the farm, Shek was gone. Ping said he had left for China to care for their sick mother. As before, he put in a crop of potatoes, and all summer he weeded and hoed and picked hungry bugs off the young plants. Then he visited a real-estate company and announced he wanted to sell the farm.

One hot day, two men drove in: a sales agent and a buyer. They wandered around, kicked the dike to test its strength and inspected the equipment. They complained about rusty hinges and the mucky puddle at the front door of the barn. Then the buyer went to the outhouse.

Suddenly Ping heard the big fellow scream and saw him flee from the outhouse. His hat flew off, but he didn't bother to stop. When his agent came running, he shouted, “Get me out of here!”

A week later, Ping saw the sales agent at the bank. “What happened that day?” he asked.

The agent drew close and lowered his voice. “That buyer said the outhouse was cold, which he found unusuÂal because the sun had been shining all day. He said when he leaned over the hole to look out the window, someone grabbed him from behind and tried to push him down the hole. He shouted and screamed, braced his arms and legs against

the

walls. It took all his strength to keep from falling into the muck. When the pushing stopped, he turned around. Nobody was there, and the door was latched on the inside!”

Ping shrugged. “I use the outhouse every day, and nothÂing has ever happened to me.”

Unfortunately, word about this strangeness leaked out, and no other buyers came by.

That year, Ping had a bumper crop of potatoes. He was willing to sell them cheaply to wholesalers, but the Marketing Board ruled that wholesalers could only buy potatoes tagged by the Board and set at a higher price. Moreover, each farmer could only sell a limited amount of potatoes. This benefited white farmers who grew smaller crops.

To Ping, this meant that no matter how many potatoes he grew, he could only sell a small amount. He and the other Chinese farmers rebelled and kept selling large quantities of potatoes at lower prices. Then the police and white farmers blocked the bridges and inspected all the Chinese trucks trying to pass. If the Board hadn't put tags on their sacks of potatoes, they weren't allowed through. Fights broke out every day.

One evening, Ping loaded his truck with potatoes and sprinted for the wholesalers in town. The roads weren't lit and he had left the truck lamps off to avoid detection. He knew the route by heart and thought no one would spot him. But near the bridge, two cars roared out of a hidden curve and forced him off the road. Ping bounced to a stop, and white men rushed out smelling of whiskey and waving flashlights.

They grabbed Ping and threw him to the ground and kicked him. Ping fought back but he was outnumbered. He felt his nose break and his cheekbone crack as he screamed in pain.

Suddenly he heard his truck engine being fired up, and then the vehicle rolled toward him. One of the white men aimed a flashlight at the steering wheel, but no one was there. Everyone jumped back, shouting and cursing.

The truck stopped and a voice shouted in Chinese, “Get in! Hurry!”

Ping clambered on. It wasn't until the truck reached the main road that he saw that Shek was driving.

Ping gasped and his hands started trembling.

“What do you want?” he asked.

Shek braked and said quietly, “Little Brother, I promised our mother that I would watch out for you.”

Then he opened the door, hopped out and vanished into the night.

Ping took a deep breath and dropped his head onto the dashboard and wept bitterly. When he recovered, he drove into town without a word. He delivered his shipment of potatoes, took the money to the steamship agent and bought passage on the next ship to China. He landed in Hong Kong and then a ferry slowly took him up the muddy river to his village.

On reaching home, he fell onto his knees before his mother and knocked his head against the floor.

“Mother, I have committed a terrible wrong,” he said in a pained voice. “I pushed Shek into the river when it was running high from the winter meltdown. I thought I was smarter than him, but he wouldn't let me sell the land, not even when he was dead. And when angry farmers almost beat me to death, Shek's spirit rescued me in the nick of time. He was a better man than me.”