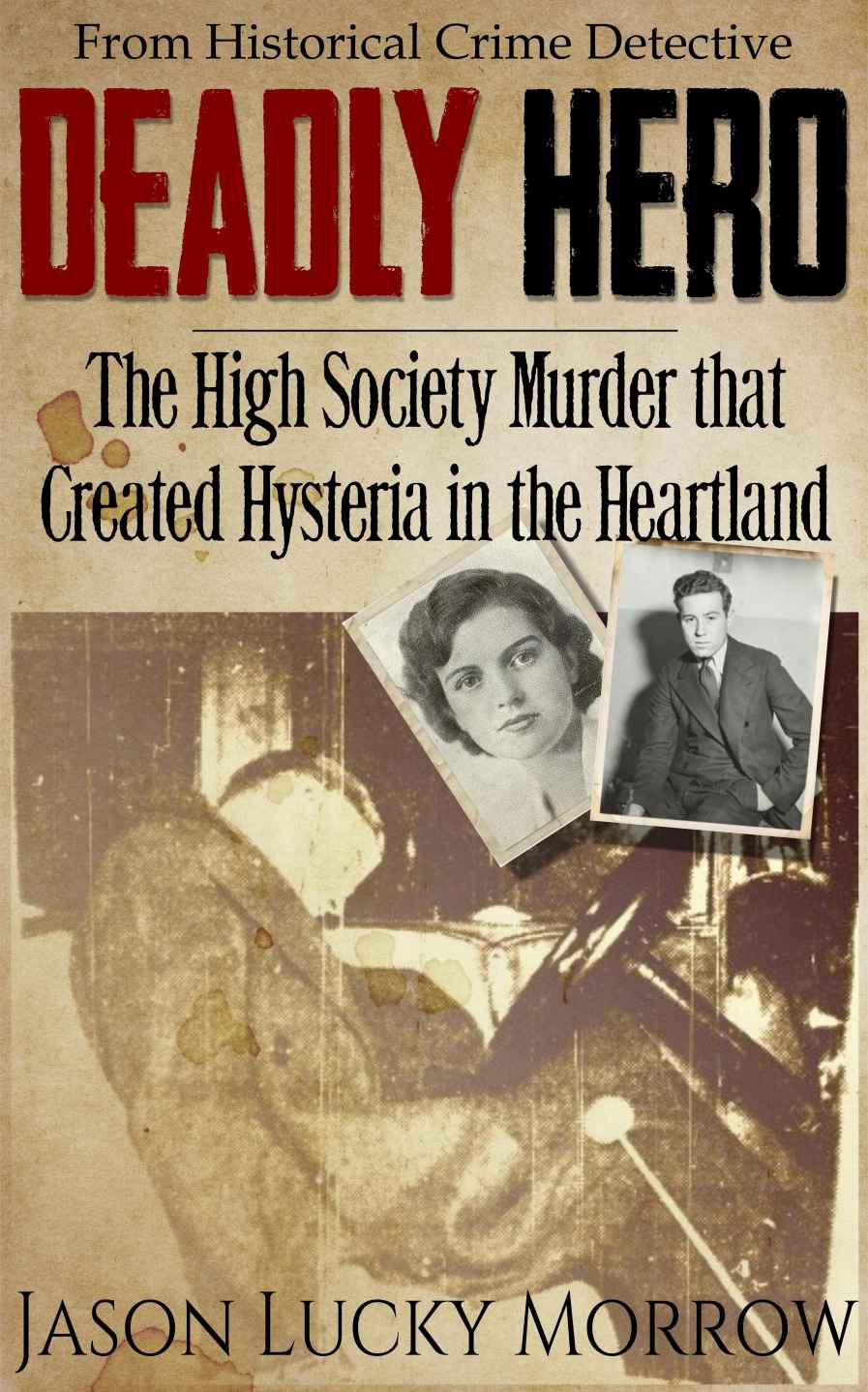

Deadly Hero: The High Society Murder that Created Hysteria in the Heartland

Read Deadly Hero: The High Society Murder that Created Hysteria in the Heartland Online

Authors: Jason Lucky Morrow

Deadly Hero

Also by Jason Lucky Morrow

The DC Dead Girls Club

: A Vintage True Crime

Story of Four Unsolved Murders in Washington D.C.

88 pages.

Kindle only $1.99 or Free for Kindle Unlimited

Subscribers.

Famous Crimes the World Forgot

: Ten Vintage True

Crime Stories Rescued from Obscurity.

288 pages.

Volume

One – Silver Medal Winner, 2015 eLit Book Awards, True Crime Category.

Kindle

only $3.95 or Free for Kindle Unlimited Subscribers.

Copyright © 2015 Jason

Lucky Morrow

All Rights Reserved

No part of this book may

be reproduced, distributed, or transmitted in any form or by any means,

including photocopying, recording, or other electronic or mechanical methods,

without the prior written permission of the author, except in the case of brief

quotations embodied in academic works, critical reviews, and certain other

noncommercial uses permitted by copyright law.

Published by: Historical

Crime Detective Books, Tulsa, OK

Editor: Gloria F Boyer,

gfboyer.com

Cover Design: Jason Morrow

ISBN-13: 978-1511991711

ISBN-10: 1511991712

ASIN: B00XLSKNI2

First Edition, 2015

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

For Mom.

A Special

Note on Historical Accuracy

AS A FORMER NEWPAPER

REPORTER, my style of writing is to craft an entertaining story, but also to

stick with the facts. I go where the research leads me and in the end, the

story is the story. All of the dialogue, quotes, and events in this book are as

they appeared in the original source materials. I have not recreated any

dialogue or manufactured events to make the story more dramatic. In some cases,

especially during the trial portion, I had to trim excess verbiage to make the

content flow more efficiently.

To help bring the characters to life, I relied on an

enormous amount of newspaper coverage to guide me in portraying body language,

facial expressions, mannerisms, gestures, and tone of voice. These character

traits are used to enhance the scene and set the mood, without altering the

facts. About half of such character traits were specifically described in the

research material. The other half of the character traits portrayed in this

book are based on clues found in the research material and should be considered

semi-fictional.

This book was written by referring to

approximately 640 newspaper articles, magazines, books, maps, census reports,

interviews, and other resources. Although I have done my best to verify the

information I have included, in any work of nonfiction, it is inevitable that

some facts or interpretations will be incorrect.

Footnotes:

I have used footnotes

throughout this book to provide clarity, perspective, or additional

information. If you are reading this book on an e-reader, I encourage you

to click the footnote links for information that will enhance your understanding

of the events and your experience of the story.

Thank

you

Before we

begin, I would like to thank you for purchasing a copy of this book. I truly

hope you enjoy this bizarre true story. If you do, I would be grateful if you

would write a review on Amazon. Your reviews will really make a difference in

the success of this book. As an independent researcher and writer, my only

sources of advertising are reviews and word of mouth. As an underdog author in

the true crime genre, I rely on my fans to spread the word.

The Murder

His teeth chattering so that he could

hardly speak, Oliver refused details until he had pushed those who met him into

the safety of the baggage room at the Claremore station.

“He is going to kill me,” Oliver

squeaked. “My God, why did I say that I would name the man who killed Gorrell?”

— Tulsa Daily

World

December 2,

1934

Friday, 12:05 a.m., November

30, 1934

WESLEY CUNNINGHAM JUST

WANTED TO get home. After his family’s Thanksgiving

[1]

meal, the seventeen-year-old

met up with friends for an evening out in downtown Tulsa that included a 9:30

showing of

College Rhythm

, followed by sandwiches and Nehi pop at the

Orpheum Theater’s lunch counter. Around midnight, Wesley said his good-byes and

sat in his family’s Ford DeLuxe while the engine warmed up. The weather had

turned ugly, and the mixture of rain and sleet would impair his visibility for

the drive home. It was time to get going.

Driving south, Wesley was just a minute or two

from reaching his stepfather’s driveway, when he saw something unusual in the

road. In front of him, on a triangular median wedged between Victor Avenue and Forest

Boulevard in the heart of Tulsa’s exclusive Forest Hills residential area, the

front end of a Ford sedan had gone partway over the median, with the back half blocking

the street. Although his headlights could barely pierce the elements to illuminate

the car, he thought he could make out a figure slumped behind the steering wheel.

Since it was a holiday weekend and college students were back in town

reconnecting with old pals, he first thought it was a rich kid living nearby

who’d had too much to drink.

He lived two blocks away and knew the area well. The

square mile of land that radiated out from the troubled car was one of the

wealthiest in the state. Several hundred yards to the west, the seventy-two-room

Philbrook Mansion sprawled out over twenty-three acres crafted into a garden

that would rival the estates of Italy on which it was modeled. Its owner, Waite

Phillips, was the younger brother of the founders of Phillips Petroleum. With

the rest of the country mired deep in the Depression, oil-rich Tulsa was

surviving marginally better than other major cities. And within that square

mile lived most of the oil barons and elite of Tulsa society.

The area was unusually dark, and Cunningham noted that

several streetlights in the vicinity were out. His car was equipped with a

spotlight, and as he pulled abreast of the Ford, he guided the beam toward the

cab.

“I saw a man, very pale, with blood running down

his face,” he would later tell police. But as he studied the situation more

carefully, he slowly began to understand that it was no drunk driver.

That

fella looked dead.

Accelerating to get out of there, Cunningham sped

to his home nearby and told his stepfather, who called police. When the patrolmen

arrived on the scene five minutes later, they checked on the driver and saw

what looked to be a bullet hole in his right temple. Blood streaks had

gravitated down in jagged lines that took several different directions. Their

first assessment of the situation led them to believe the young man had shot

himself while the car was still in motion, which might explain why it had gone

over the curb. They did find a gun in the car, but it wasn’t where they thought

it would be. Instead, it was tucked neatly in a leather shoulder holster that lay

on the seat next to him.

That was odd.

From the description given by Wesley’s stepfather,

the police dispatcher assumed the Ford’s occupant was dead, and at 12:20 a.m.

he notified Sergeant Henry B. Maddux, who was on duty. Maddux was the police

department’s criminologist and second-in-command of the detective bureau. He’d

been hired in January by a progressive new fire and police commissioner, and his

boyish face misled others into thinking he was much younger than his

thirty-five years.

There was virtually no traffic on the wet streets

as Sgt. Maddux, accompanied by Detective George Reif, drove to the scene. When they

arrived at the triangular median, the investigators found the whole area

unusually dark. Looking around, they noticed several streetlamps were out. They

would need more light. Maddux ordered a patrolman and Detective Reif to reposition

their patrol vehicles so that the victim’s car was in the middle, lit by four

headlight beams.

Peering through the open passenger door, Maddux

immediately noticed the death car was still in gear, and the ignition switch

had not been cut off. When the Ford jumped the curb, it had apparently shut the

motor off. Turning his attention to the dead man, Maddux found that aside from

the streaks of blood and a small bruise over his right eye, the young driver

appeared peaceful. His clothing was in perfect order, and his dark, wavy hair was

still carefully in place. His feet were still on the clutch and gas pedals, and

his right fingers were touching a leather holster that held a revolver.

That didn’t sit right with him. How does a man

with a bullet in his head put a revolver back in the holster? He didn’t know

where this case was going to lead, but his training told him photographs of the

dead driver would be needed. As Detective Reif pointed a flashlight toward the

cab, Maddux adjusted the Kalart flash, peered through the Kodak’s viewfinder,

and snapped a picture.

After handing the camera off to Reif, Maddux

carefully reached into the dead man’s coat and, from an inside pocket, retrieved

a wrinkled envelope addressed to John Gorrell Jr., at 1205 Linwood Boulevard,

Kansas City, Missouri. The return address was 2116 East 15

th

Street,

Tulsa, Oklahoma, and the letter was apparently from the boy’s mother.

John Gorrell Jr.?

Maddux didn’t know the name but Reif did; John

Gorrell Sr. was a prominent local physician, and if this was his son, it was a

bit of a surprise to both of them. There had been a lot of suicides lately, but

most of those were by men who had lost fortunes or were beaten down by the

Depression. But as he tilted the boy’s head and aimed Reif’s flashlight toward

the grisly wound, he made a discovery that would eventually turn the entire

city of Tulsa inside out.

There were two bullet holes in the side of Junior’s

head.

Maddux called Reif to take a look and told the

young detective to keep the fact that this was now a murder investigation a

secret. Maddux made an instant decision to throw off the killer by letting him

think the police believed it was a suicide. He wanted the shooter to relax and

let his guard down.

The sergeant then turned his attention to the

revolver jammed tightly into a leather shoulder holster on the seat next to him.

With his handkerchief, Maddux lifted the holster from the edge and gingerly

placed it in a paper sack. If it was the murder weapon, then fingerprints might

link it to the killer. The barrel protruded through the bottom of the holster,

and judging by its smell, it had recently been fired. But a more detailed

examination would have to wait until later that morning, after Maddux notified

the boy’s parents.

In spite of the late hour, the commotion attracted

a small crowd of onlookers. Across the street, the grounds of the Cornelius

Titus mansion were well lit, but not enough to reach across the street. Parked

in a car nearby were two security guards who worked for Mr. Titus. Sergeant

Maddux, a man who lived with his wife in a modest apartment, looked around the

area and understood that this was the part of town where the rich people lived.

It was not going to be a routine murder investigation.

As he warned the patrolmen to guard the scene

until the coroner arrived, one of them directed the senior lawman’s attention

to Wesley Cunningham, who had returned to the area.

“As I turned off Forest Boulevard, I noticed the

car,” Cunningham explained to Maddux. “It looked as if there had been some sort

of accident. I stopped when I was abreast of the car and turned on my

spotlight.”

He then told of how he had seen the lines of blood

on the right side of the man’s pale face and had sped home to tell his stepfather,

who then called police at 12:15 a.m. He estimated five to ten minutes had

passed from the time he discovered the car to when the phone call was made.

That would put the time of death sometime before midnight,

Maddux would later report.

When the police sergeant reached the Gorrell home,

a reporter for the

Tulsa Daily World

had already broken the news to the

family. With a lack of sensitivity, the writer asked Dr. Gorrell if he thought

his son could have committed suicide, a theory being advanced by police.

“Ridiculous,” Dr. Gorrell said, while standing in

the doorway, dressed in his pajamas. “John was in the best of spirits

yesterday. He had been attending dental school in Kansas City and only got home

yesterday morning for the holidays. I know that he would not kill himself. He

was not the type.”

Both parents were emphatic in their opinion that John

had had no reason to commit suicide. He was a normal, vibrant, young man who

was intensely interested in joining the dental profession and was engaged to an

attractive young woman living in Pittsburg, Kansas.

With a scornful look to the reporter, Sgt. Maddux

introduced himself and was let into the Gorrell home. At the same dining-room

table used by the family just hours before, Maddux proceeded slowly with his

questions to the grieving parents. He needed a timeline of their son’s

activities that day, where he was, and who

he was with.

John had returned early that morning from Western

Dental College in Kansas City, where the twenty-one-year-old shared a room with

two other Tulsa boys, Richard Oliver and Jess Harris, the parents told him. Oliver

had stayed in Kansas City, but Harris and Gorrell

drove back to Tulsa in

the Ford. Around noon, John reconnected with his pal Charles Bard, who was home

from Oklahoma A&M.

[2]

The two of them then attended a University of Tulsa football game before having

Thanksgiving dinner at the Gorrell home. It was a normal day, but what they

told Sgt. Maddux next caught his interest.

Thirty minutes into the family dinner, they were

interrupted by a telephone call. Mrs. Gorrell pushed her chair back from the

table to answer the phone, but John was already out of his. There were eight people

at the dinner table that night: John and his younger siblings, Edith Ann and

Ben; Charles Bard; Dr. and Mrs. Gorrell; and two adult guests.

“No, I’ll go, Mother,” John had said as he walked

to an adjoining hallway where the family telephone was located. His mother

couldn’t make out what he was talking to the caller about, but when he returned

to the dining room, she could tell something was wrong. The sparkle had left

his eyes, and his face was blanched and tight.

“He looked to be in a state of suppressed nervous

excitement,” Mrs. Gorrell said. “When I asked what was wrong, he said ‘nothing.’”

But just a few minutes later, John announced he

and Charles had dates that night, and they excused themselves from the table.

They ran upstairs to John’s room to get ready and came back down around 7:20 p.m.

When they came back down, his mother could hear the clicking of the telephone

dial as her son made a call and then John speaking in a low mumble. After he

was done, John and Charlie walked by the crowded dining table toward the front

door. She asked her son where he was going and received a terse reply.

“Don’t ask me, Mother.”

That was the last time she saw her son alive.

BACK AT THE CRIME SCENE, reporters for the

Tulsa

World

and

Tulsa Tribune

were moving through the growing crowd,

looking for neighbors to interview. Frank Moss, one of the night watchmen for

the Titus estate, had heard five shots earlier that night. At nine o’clock, he had

heard three shots, then the sound of a car speeding away, and then later, two

more shots. His partner, Carl Rust, had also heard shooting.

“I heard three shots and then the sound of racing

cars,” Rust told a

World

reporter. “They came around the curve from over

the hill, and then there were two more shots. The cars separated. One of them

drove toward town, and the other turned down in such a way that it could have

been just where this one was found.”

Rust assumed it was young people still celebrating

the holiday. He judged the incident as unimportant until he noticed all the activity

where Gorrell’s car was found. Somehow, the two night watchmen had not noticed

the Ford until the police had shown up.

Sergeant Maddux’s strategy of publicizing a

suicide theory, with the intention of getting the killer to let his guard down,

lasted only a few hours. As reflected in the morning paper, reporters had

learned Gorrell had been shot in the head, twice, and the probable murder

weapon was his own revolver, which was returned to the shoulder holster that

rested on the seat. That information came from police Captain J. D. Bills, who

apparently wasn’t in on the secret.

After the body was removed by the coroner, Maddux

and Reif directed their attention back to the streetlights. Two of them were

out, including one with a shattered bowl that was near the Gorrell car. They

weren’t sure what to make of this detail, or if it was even connected to the

murder. For now, they needed to find Charlie Bard, and they needed to find the

two young ladies the boys had been with the night before. To solve this case,

Maddux and his detectives would have to reconstruct every minute of the nearly five

hours between 7:30 p.m. and 12:10 a.m.