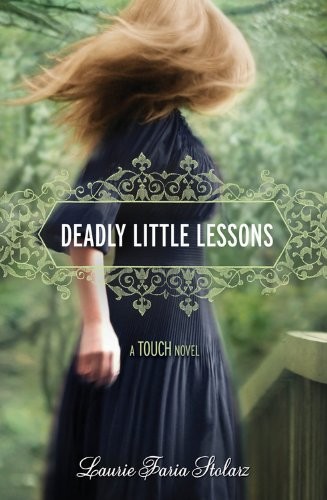

Deadly Little Lessons

Read Deadly Little Lessons Online

Authors: Laurie Faria Stolarz

Tags: #Juvenile Fiction, #Fantasy & Magic, #Family, #Adoption, #Social Issues, #Adolescence, #Fiction - Young Adult

Copyright © 2012 by Laurie Faria Stolarz

All rights reserved. Published by Hyperion, an imprint of Disney Book Group. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system, without written permission from the publisher. For information address Hyperion, 114 Fifth Avenue, New York, New York 10011-5690.

ISBN 978-1-4231-7916-0

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Chapter 1

- Lesson Number One

- Chapter 2

- Chapter 3

- Chapter 4

- Chapter 5

- Lesson Number Two

- Chapter 6

- Chapter 7

- Chapter 8

- Lesson Number Three

- Chapter 9

- Chapter 10

- Chapter 11

- Chapter 12

- Chapter 13

- Chapter 14

- Lesson Number Four

- Chapter 15

- Chapter 16

- Chapter 17

- Chapter 18

- Chapter 19

- Lesson Number Five

- Chapter 20

- Chapter 21

- Chapter 22

- Chapter 23

- Chapter 24

- Chapter 25

- Lesson Number Six

- Chapter 26

- Chapter 27

- Chapter 28

- Chapter 29

- Chapter 30

- Chapter 31

- Lesson Number Seven

- Chapter 32

- Chapter 33

- Chapter 34

- Chapter 35

- Chapter 36

- Lesson Number Eight

- Chapter 37

- Chapter 38

- Chapter 39

- Chapter 40

- Chapter 41

- Chapter 42

- Chapter 43

- Lesson Number Nine

- Chapter 44

- Chapter 45

- Chapter 46

- Chapter 47

- Lesson Number Ten

- Chapter 48

- Chapter 49

- Chapter 50

- Chapter 51

- Chapter 52

- Chapter 53

- Chapter 54

- Chapter 55

- Chapter 56

- Acknowledgments

T

HERE’S A STABBING SENSATION

in my chest. It pushes through my ribs, making it hard to breathe.

I’ve felt this way since last night. Since the phone rang and I decided to answer it.

The caller ID screen flashed:

PRIVATE CALLER

.

I wish I had let my parents get it. The last thing I needed was another faceless person on the other end of a phone, especially considering everything I’d already been through during the past year.

But instead I picked it up.

“Camelia?” an unfamiliar female voice asked.

My chest tightened instinctively. “Who is this?”

“It’s your grandmother.”

But it didn’t sound anything like my grandmother. This person’s voice was less cheerful, more distant.

“Your

mother’s

mother,” she said, to clarify.

It took my brain a beat to make sense of her words, after which my whole body tensed.

“I know it’s been a little while,” she continued, “but I really need to speak to your mother.”

I wanted to ask her why—what she could possibly want. My mother hadn’t seen or spoken to my grandmother in at least twelve years.

“I heard your mother is staying at your home, is that true?” she asked, when I didn’t say anything.

“Staying at my home?” I felt both dazed and confused, like in that Led Zeppelin song from the ’60s.

“Your mother,” she attempted to explain. “I heard that she’s moved in with you. Is she there? Can I speak with her?”

Moved in with me?

“My mother lives here,” I told her. “This

is

her home.”

“Well, then, please,” she insisted (her voice sounded sharp and irritated now), “can you simply put Alexia on the phone for me? This is rather urgent.”

“Alexia?” I said, assuming that she was confused, too. “Aunt Alexia

was

staying here. A few months ago.”

But

now she’s locked up in the mental ward at the local hospital. And

the way that you treated her as a child—resenting her for having

ever been born—is at least partially to blame for her instability.

“Do you want to talk to my mother instead?” I asked.

“Your mother.” There was a tinge of amusement in her voice. “Don’t you know? What have they told you, dear?”

“Excuse me?”

“Alexia

is

your mother, Camelia. Certainly you must know the truth by now.…”

“What?”

I asked, but I’m not even sure the word came out.

“Alexia is your mother,” she repeated, louder, more forcefully, as if I hadn’t quite heard her the first time.

My heart pounded. An array of colors bled in front of my eyes, and the room began to darken and whirl.

“Camelia?”

The receiver fell from my grip.

I sank to my bed, where I’ve remained ever since, replaying the phone conversation in my head, dissecting each sentence, word, syllable, and letter, hoping that maybe I misunderstood. But no matter how many times I try to pick her words apart, the meaning is still the same.

There’s a knock at my bedroom door. I roll over and bury my head beneath my pillow, hoping that whoever it is will just go away. But a couple of seconds later, the door opens. Footsteps creak across the floorboards.

“Camelia?” Dad asks.

I clutch the ends of the pillow.

“It’s almost noon,” he says. “I thought we’d go out for brunch. Anywhere you want.”

“I’m not hungry.”

“Are you not feeling well?” He attempts to pry the pillow from over my head, but he’s no match for me.

“Headache,” I tell him. The knifelike sensation burrows deeper into my chest. Talking feels both labored and painful.

“Well, can I get you anything? Tea, aspirin, something to eat? I could bring you some toast.…”

“Nothing,” I say, wondering if he notices that I’m still in my clothes from yesterday; that I never changed for bed; that the phone receiver is still on the floor; or that my pillow is soiled with tears and day-old makeup.

“Okay, well maybe I’ll make you something anyway,” he says, lingering a moment before he finally leaves.

Alone again, I attempt to let out a breath, but the sharp sensation in my chest keeps it in. I know there are a million things that I should do right now—that I

could

do—to try to ease this ache: talk to him and/or Mom; call Dr. Tylyn; phone Kimmie; or text Adam at work to come and pick me up. But instead I replay the phone conversation just one more time.

He slides a tape recorder toward my feet, through the hole in the wall—the wall that separates him from me.

I’m confined underground, in the dark, in a cell made of cinder blocks and steel. The hole—just big enough to fit both of my hands through—is the only visible opening in the cell. There are no doors, no windows.

“Where’s the trash?” he barks. His voice makes me shiver all over. He sets his lantern down on the ground; I hear the familiar clunk against the dirt floor. The lantern’s beam lights up his feet: work boots, soiled at the toe, laces that have been double-knotted. “I shouldn’t have to ask for it every time.”

Time. How long

has

it been? Two weeks? Two months? Was I unconscious for more than a day? He took my wristwatch—the purple one with the extra-long strap that wound around my wrist like a bracelet. My father gave it to me for my fifteenth birthday, just before I found out the truth. And now I may never see my father again. The thought of that is too big to hold in; a whimper escapes from my mouth. Tears run down my cheeks. I hate myself for being here. I hate even more the fact that I probably deserve it.

I lean forward, pushing my plastic bowl through the hole, eager to appease him. Hours earlier, he’d filled the bowl with stale crackers and had given me a lukewarm cup of tea. My stomach grumbles for a hot meal, though the thought of eating one makes me sick.

He snatches the bowl and then pushes the tape recorder a little further inside. As he does so, I catch another glimpse of the mark on his hand, on the front of his wrist. I think it might be a tattoo.

“What is this for?” I ask, referring to the tape recorder. Aside from the clothes on my back, my only current possessions are those he’s given me: a flashlight, a blanket and pillow, a roll of toilet paper, a basin of water, and a cat litter box. If it weren’t for the flashlight, I’d be totally in darkness.

I shine my flashlight over the recorder; it’s the old-fashioned kind.

He feeds a microphone through the hole. There’s a cord attached to the handle. “Only speak when spoken to,” he reminds me. “Now, be a good girl and plug the mic into the recorder,” he continues.

With jittery fingers, I do what he says, fumbling as I try to plug the cable into the hole at the side, finally succeeding on the fifth try.

“I want you to record yourself,” he says. “Tell me what you love and what you hate. What scares you the most.”

“What scares me?” More tears drip down my cheeks.

I’m scared that I’ll never get out of here. I’m scared that I’ll never

get to see my parents again, and that I’ll have to pay for what

I did.

I move my flashlight beam up the wall. Unlike the cinder-block back and side walls, the front of the cell has a solid steel frame, consisting of a locked steel door, similar to that of a prison cell (except with no bars to look out).

“As you can imagine, I love a good scare.” He laughs.

I huddle into the far corner of the cell and pull the blanket over me, still trying to piece together what happened the night I was taken.

I remember talking to him for at least an hour at the bar and then following him out a side door. We walked toward the back of the building, where his car was supposedly parked. It was dark—a spotlight had busted—and we were passing by some trash cans. I remember trying to keep my balance while standing on a lid. Why was I doing that? And what happened afterward? Did I fall? Did anyone see me? Did I pass out before we drove away?

“Whatever you do, don’t waste my time,” he snaps. “Don’t record how much you hate it here, or how you think I’m a monster. Those opinions are irrelevant to me. Is that understood?”

I nod, even though he can’t see me, and dig my fingers into the dirt floor, trying my best to be strong.

“I’ll be back in an hour,” he says, as if time had any meaning for me since I don’t have a watch.

I nibble on my fingernails, too nervous to care that they’re covered in dirt. “Can I have more water first?” I ask, knowing that I’m speaking without permission, but needing to, because my throat feels dry, like sandpaper.

“Not until the tape’s done,” he snaps again.

I listen as he walks away, the soles of his shoes scuffing against the dirt floor. The door he entered by—the one that leads to a set of stairs (I’ve seen it through the hole in the wall)—creaks open, then slams shut. Those sounds are followed by more noises: bolts and locks and jingling keys.

I remain huddled up, trying to reassure myself that I’m still alive, and that I’m still wearing the same clothes as the night I was taken, so he probably never touched me in any weird way. Maybe there’s hope. Maybe once I’m done with his tape-recording project, he’ll finally set me free.