Dean and Me: A Love Story

Read Dean and Me: A Love Story Online

Authors: Jerry Lewis,James Kaplan

Tags: #Fiction, #Non-Fiction, #Music, #Humour, #Biography

Table of Contents

MARTIN & LEWIS BOOED AT PALLADIUM OPENING

In Tonight’s Performance, Miss Carol Haney’s Role Will Be Played by Miss Shirley MacLaine

For Dani, the young lady who is the air in my lungs,

and her young mother, who is the beat in my heart,

thank you both for getting me to here.

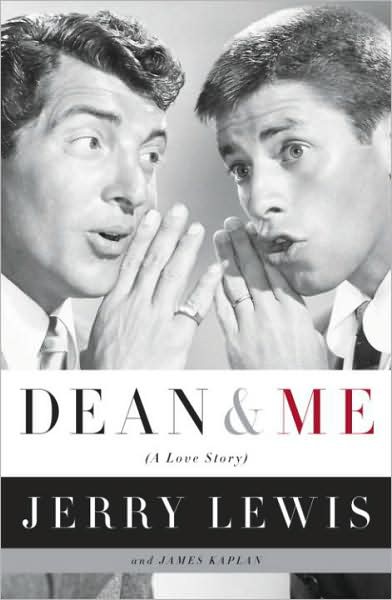

PHILIPPE HALSMAN,

LIFE,

1951

PROLOGUE: BREAKING UP

MOST OF THE OUTSIDE WORLD WASN’T AWARE OF THE GULF that had grown between us, and we were still making money like the U.S. Mint. But there was no getting around it: The time had come to call it a day. In the coolest, most practical way, Dean and I decided to go out on top.

On Tuesday night, July 24, 1956—ten years to the day after our first appearance together at Skinny D’Amato’s 500 Club in Atlantic City— we played our last three shows, ever, at the Copacabana, on East Sixtieth Street in Manhattan.

The evening quickly took on the magnitude of a great event. After all, for the past decade, Martin and Lewis had delighted America and the world. We’d been loved, idolized, sought after. And now we were shutting the party down.

The celebrity guest list for this night of nights grew and grew. With about a half hour before our first show, Dean and I had very little to say to each other. It was going to be a rough night, but we both knew we couldn’t allow ourselves to be sloppy or unprofessional. So our plan was to have fun, if possible, and to do the best show we knew how to do.

I walked across the hall to my partner’s suite at about 7:35 for absolutely no reason other than to announce that I needed ice. Dean always had ice. I walked over to the bar and put some in my glass. He gave me a knowing glance—he felt what I felt and we didn’t have to expound on it. I managed to get myself to the door and croaked out, “Have a good show, Paul.” (That was his middle name, what I always called him.) He said, “You too, kid.”

I walked out into the hallway and thought my heart would break. I was losing my best friend and I didn’t know why. And if I had known why, would that have made a difference? I now think that since it had to happen, at least it happened quickly. When husbands and wives break up, it can take years, or they stay together for all the wrong reasons.

Dean and I knew we had to get on with our lives, and being a team no longer worked. As sentimental as it sounds, we both had the hand of God on us until even He said, “Enough!”

I think for the most part we understood what was happening. We were just scared, and didn’t want anyone to know. Scared about where we were going and what we would be doing. We had become accustomed to our fabulous lifestyle. Would the autograph-seekers still seek? Could we do

anything

without each other? Would we be accepted as anything other than what we had been?

Dean had this uncanny way of making everything bad look like it wasn’t all

that

bad. It wasn’t denial, it was that he never had sweaty palms. No matter how things turned out, Dean could make it seem as if that was the way he’d planned it.

One look at my face and you knew despair . . . joy . . . happiness . . . sorrow. My dad called me “Mr. Neon”—and he was right. I always had to let everyone know what I was feeling. Anything else and I felt like a liar. Truth was my greatest ally. Painful, yes, but I found it was the only way for me. Dean could lie if it would spare someone’s feelings. I had difficulty with that.

Well, however we felt, my partner and I still had three final shows to do at the Copa, and it was getting to be that time.

I always went on before Dean, did my shtick and introduced him. He would hang back on the top level of the Copa, greeting people and making nice while I was out there, setting them up for his entrance. But this night, when it came time for me to say, “And here’s my partner, Dean Martin,” the words stuck in my throat. The audience knew it was the last night I would ever say those words, and the air was filled with a kind of exquisite trauma, the star-studded crowd hoping—perhaps—for a last-minute reprieve.

It was an eerie and uncertain feeling out there. I wasn’t sure myself if the powerful vibrations in the Copa were good or bad. We had to do that first show to find out a lot of things.

So Dean strolled out, as he always did . . . cool, relaxed-looking—but I knew my partner. His eyes told me he was feeling the same pain and uncertainty that I was.

We shook hands, as we always did, but this time a murmur swept through the audience. “Maybe there

is

a chance?”

It vibrated through the entire building.

Dean did his three songs, uneventfully, pretty much the way he’d always done them, and out I came to go into our routine. “It’s nice that you cut down your songs to only eleven numbers. I thought I’d have to shower again! It don’t say outside, ‘Dean Martin,’ period . . . it says ‘Dean Martin and Jerry Lewis’! Did you forget, or are you anxious to be out of work?”

All of that was what we always did, only on this night every joke had too much significance. We forged ahead, knowing that soon we would be finished: Only two more shows to go, and it would be over.

We barreled through what we had to do and came to the last song in the act, “Pardners.”

You and me, we’ll always be pardners,

You and me, we’ll always be friends.

Now, singing that number could have been a mistake, because once we got into it, that audience changed from uncertain to sure; it was over, and they were watching everything but the burial. We finished the song, and the applause was deafening.

We finished the second show, and the third went on at 2:30 A.M. sharp. This time Dean and I both knew:

This is it! The last time . . . never

again . . . all over . . .

It felt like being choked without hands on your throat. But here it is. It’s 2:25, and Dean is standing at his place at the foot of the stairs, stage right . . . and I’m standing at the foot of the stairs, stage left. The Copa Girls go by us as they finish the opening production number, and as they pass, they too are teary-eyed. Rather than rush to their dressing rooms, they stand along the staircases on both sides of the stage to watch. They all felt the death knell, and they wanted to be a part of it.

So we went on and killed them, and killed ourselves as well. We were both shattered by the time we got to “Pardners,” and we didn’t even do it too terribly well, but we got through it, and as that audience rose to celebrate all we had ever done, they knew it was over. There were shouts, tears, applause. It was midnight on New Year’s Eve all over again—and in July, yet.

Dean and I both headed for the elevator, waving off all comers. When the door closed, we put our arms around each other, just letting go the floodgates. We arrived at our floor and got out, and thank God, no one was around. We went to our suites and closed the doors. I grabbed the phone and dialed Dean.

“Hey, pally,” he said. “How’re you holdin’ up?”

“I don’t know yet. I just want to say—we had some good times, didn’t we, Paul?”

“There’ll be more.”

“Yeah, well, take care of yourself.”

“You too, pardner.”

We hung up and closed the book on ten great years—with the exception of the last ten months. They were horrific. Ten months of pain and anger and uncertainty and sorrow.

Now it was time to pick up the pieces. Not so easy. . . .

CHAPTER ONE

IN THE AGE OF TRUMAN, EISENHOWER, AND JOE MCCARTHY, we freed America. For ten years after World War II, Dean and I were not only the most successful show-business act in history—we were history.

You have to remember: Postwar America was a very buttoned-up nation. Radio shows were run by censors, Presidents wore hats, ladies wore girdles. We came straight out of the blue—nobody was expecting anything like Martin and Lewis. A sexy guy and a monkey is how some people saw us, but what we really were, in an age of Freudian self-realization, was the explosion of the show-business id.

Like Burns and Allen, Abbott and Costello, and Hope and Crosby, we were vaudevillians, stage performers who worked with an audience. But the difference between us and all the others is significant. They worked with a script. We exploded without one, the same way wiseguy kids do on a playground, or jazz musicians do when they’re let loose. And the minute we started out in nightclubs, audiences went nuts for us. As Alan King told an interviewer a few years ago: “I have been in the business for fifty-five years, and I have never to this day seen an act get more laughs than Martin and Lewis. They didn’t get laughs—it was pandemonium. People knocked over tables.”

Like so many entertainment explosions, we happened almost by accident.

It was a crisp March day in midtown Manhattan, March of 1945. I had just turned nineteen, and I was going to live forever. I could feel the bounce in my legs, the air in my lungs. World War II was rapidly drawing to a close, and New York was alive with excitement. Broadway was full of city smells—bus and taxi exhaust; roast peanuts and dirty-water hot dogs; and, most thrilling of all, the perfumes of beautiful women. Midtown was swarming with gorgeous gals! Secretaries, career girls, society broads with little pooches—they all paraded past, tick-tock, tick-tock, setting my heart racing every ten paces. I was a very young newly-wed, with a very pregnant wife back in Newark, but I had eyes, and I looked. And looked. And looked.

I was strolling south with my pal Sonny King, heading toward an appointment with an agent in Times Square. Sonny was an ex-prizefighter from Brooklyn trying to make it as a singer, a knock-around guy, street-smart and quick with a joke—kind of like an early Tony Danza. He prided himself on his nice tenor voice and on knowing everybody who was anybody in show business. Not that his pride always matched up with reality. But that was Sonny, a bit of an operator. And me? I was a Jersey kid trying to make it as a comic. My act—are you ready for this?— was as follows: I would get up on stage and make funny faces while I lip-synched along to phonograph records. The professional term for what I did was

dumb act

, a phrase I didn’t want to think about too much. In those days, it felt a little too much like a bad review.

You know good-bad? Good was that I was young and full of beans and ready to take on the world. Bad was that I had no idea on earth how I was going to accomplish this feat. And bad was also that I was just eking out a living, pulling down $110 a week in a good week, and there weren’t that many good weeks. On this princely sum I had to pay my manager, Abner J. Greshler, plus the rent on the Newark apartment, plus feed two, about to be three. Plus wardrobe, candy bars, milk shakes, and phonograph records for the act. Plus my hotel bill. While I was working in New York, I stayed in the city, to be close to my jobs—when I had them—and to stick to where the action was. I’d been rooming at the Belmont Plaza, on Lexington and Forty-ninth, where I’d also been performing in the Glass Hat, a nightclub in the hotel. I got $135 a week and a room.

Suddenly, at Broadway and Fifty-fourth, Sonny spotted someone across the street: a tall, dark, and incredibly handsome man in a camel’shair coat. His name, Sonny said, was Dean Martin. Just looking at him intimidated me:

How does anybody get that handsome?

I smiled at the sight of him in that camel’s-hair coat.

Harry Horseshit

, I thought. That was what we used to call a guy who thought he was smooth with the ladies. Anybody who wore a camel’s-hair overcoat, with a camel’s-hair belt and fake diamond cuff links, was automatically Harry Horseshit.

But this guy, I knew, was the real deal. He was standing with a shorter, older fellow, and when he saw Sonny, he waved us over. We crossed the street. I was amazed all over again when I saw how good-looking he was—long, rugged face; great profile; thick, dark brows and eyelashes. And a suntan in March! How’d he manage that? I could see he had kind of a twinkle as he talked to the older guy.

Charisma

is a word I would learn later. All I knew then was that I couldn’t take my eyes off Sonny’s pal.

“Hey, Dino!” Sonny said as we came up to them. “How ya doin’, Lou?” he said to the older man.

Lou, it turned out, was Lou Perry, Dean’s manager. He looked like a manager: short, thin-lipped, cool-eyed. Sonny introduced me, and Perry glanced at me without much interest. But Sonny looked excited. He turned to his camel-coated friend. “Dino,” Sonny said, “I want you to meet a very funny kid, Jerry Lewis.”

Camel-Coat smiled warmly and put out his hand. I took it. It was a big hand, strong, but he didn’t go overboard with the grip. I liked that. I liked

him

, instantly. And he looked genuinely glad to meet me.

“Kid,” Sonny said—Sonny called me Kid the first time he ever met me, and he would still call me Kid in Vegas fifty years later—“this is Dean Martin. Sings even better than me.”

That was Sonny, fun and games. Of course, he had zero idea that he was introducing me to one of the great comic talents of our time. I certainly had no idea of that, either—nor, for that matter, did Dean. At that moment, at the end of World War II, we were just two guys struggling to make it in show business, shaking hands on a busy Broadway street corner.

We made a little chitchat. “You workin’?” I asked.

He smiled that million-dollar smile. Now that I looked at him close up, I could see the faint outline of a healing surgical cut on the bridge of his nose. Some plastic surgeon had done great work. “Oh, this ’n’ that, you know,” Dean said. “I’m on WMCA radio, sustaining. No bucks, just room.” He had a mellow, lazy voice, with a slightly Southern lilt to it. He sounded like he didn’t have a care in the world, like he was knockin’ ’em dead wherever he went. I believed it. Little did I know that he was hip-deep in debt to Perry and several other managers besides.

“How ’bout you?” Dean asked me.

I nodded, quickly. I suddenly wanted, very badly, to impress this man. “I’m just now finishing my eighth week at the Glass Hat,” I said. “In the Belmont Plaza.”

“Really? I live there,” Dean said.

“At the Glass Hat?”

“No, at the Belmont. It’s part of my radio deal.”

Just at that moment, a beautiful brunette walked by, in a coat with a fur-trimmed collar. Dean lowered his eyelids slightly and flashed her that grin—and damned if she didn’t smile right back! How come I never got that reaction? She gave him a lingering gaze over her shoulder as she passed, a clear invitation, and Dean shook his head, smiling his regrets.

“Look at this guy,” Sonny said in his hoarse Brooklyn accent. “He’s got pussy radar!”

One look at Sonny’s eyes was enough to tell me that he idolized Dean—whose attention, all at once, I felt anxious to get back. “You ever go to Leon and Eddie’s?” I asked, my voice sounding even higher and squeakier than its usual high and squeaky. Leon and Eddie’s was a restaurant and nightclub a couple of blocks away, on fabulous Fifty-second Street—which, in those days, was lined with restaurants and former speakeasies, like “21,” and music clubs like the Five Spot and Birdland. Live entertainment still ruled America in those pretelevision days, Manhattan was the world capital of nightclubs, and Leon and Eddie’s was a mecca for nightclub comics. Sunday night was Celebrity Night: The fun would start after hours, when anybody in the business might show up and get on to do a piece of their act. You’d see the likes of Milton Berle, Henny Youngman, Danny Kaye. It was magical. I used to go and gawk, like a kid in a candy store. Someday, I thought. . . . But for now, no chance. They’d never use a dumb act—one needing props, yet.

“Yeah, sometimes I stop by Sunday nights,” Dean said.

“Me too!” I cried.

He gave me that smile again—warm but ever so slightly cool around the edges. It bathed you in its glow, yet didn’t let you in. Men don’t like to admit it, but there’s something about a truly handsome guy who also happens to be truly masculine—what they call a

man’s man

—that’s as magnetic to us as it is to women.

That’s what I want to be like

, you think.

Maybe if I hang around with him, some of that’ll rub off on me.

“So—maybe I’ll see you there sometime,” Dean told me.

“Yeah, sure,” I said.

“Go get your tux out of hock,” he said.

I laughed. He was funny.

Sonny King was a pal, but not a friend. I badly needed a friend. I was a lonely kid, the only child of two vaudevillians who were rarely around. My dad, Danny, was a singer and all-around entertainer: He did it all— patter, impressions, stand-up comedy. My mom, Rachel (Rae), was Danny’s pianist and conductor. So I grew up shuttled from household to household, relative to relative. I cherished the precious times Mom and Dad would take me on the road with them. And for them, the highest form of togetherness was to put me right in the act: My first onstage appearance was at age five, in 1931, at the President Hotel, a summer resort in Swan Lake, New York. I wore a tux (naturally) and sang that Depression classic “Brother, Can You Spare a Dime?” From that moment on, showbiz was in my blood. So was loneliness.

By the time I was sixteen, I was a high-school dropout and a show-business wannabe. A

desperately

-wanting-to-be wannabe. I worked the Catskill resorts as a busboy (for pay) and (for free) a tummler—the guy who cuts up, makes faces, gets the guests in a good mood for the real entertainment. That’s what I wanted to be, the real entertainment. But what was I going to do? I was tall, skinny, gawky; cute but funny-looking. With the voice God had given me, I certainly wasn’t going to be a singer like my dad, with his Al Jolson baritone. I always saw the humor in things, the joke possibilities. At the same time, I didn’t have the confidence to stand on a stage and talk.

Then I hit on a genius solution—or what seemed at the time like a genius solution. One night, at a New Jersey resort where my parents were doing their act, a friend of mine, an aspiring performer, Lonnie Brown—the daughter of Charlie and Lillian Brown, resort hotelkeepers who were destined to become very important in my life—was listening to a record by an English singer named Cyril Smith, trying to learn those classy English intonations. I had a little crush on Lonnie, and, attempting to impress her, I started to clown around, mouthing along to the music, rolling my eyes and playing the diva. Well, Lonnie broke up, and

that

was music to my ears. An act was born.

After a couple of hard years on the road, playing burlesque houses where the guys with newspapers on their laps would boo me off the stage so they could see the strippers, I became a showbiz veteran (still in my teens) with an act called “Jerry Lewis—Satirical Impressions in Pantomimicry.”

I had perfected the act, and to tell the absolute truth, it was pretty goddamn funny. I would put on a fright wig and a frock coat and lipsynch to the great baritone Igor Gorin’s “Largo Al Factotum” from

The

Barber of Seville.

I’d come out in a Carmen Miranda dress, with fruit on my hat, and do Miranda. Then into a pin-striped jacket, suck in my cheeks, and I’d do Sinatra singing “All or Nothing at All.” I knew where every scratch and skip was on every record, and when they came up, I’d do shtick to them. I had gotten better and better at contorting my long, skinny body in ways that I knew worked comedically. I practiced making faces in front of a mirror till I cracked myself up. God hadn’t made me handsome, but he’d given me

something

, I always felt: funny bones.

And I never said a word on stage.

The dumb act was a rapidly fading subspecialty in those rapidly fading days of baggy-pants comedy, and my own days doing it were numbered. There were a few of us lip-synchers out there, working the circuit, and while I liked (and still like) to think that I was the best of the bunch—nobody could move or pratfall or make faces like Jerry Lewis— I only had around three to eleven audience members per show who agreed with me. Those three or four or nine people would be wetting themselves while I performed, as the rest of the house (if anyone else was there) clapped slowly, or booed. . . . Bring on the strippers!

And I never said a word.

The truth is, funny sentences were always running through my brain: I

thought

funny. But I was ashamed of what would come out if I spoke—that nasal kid’s voice. So I was funny on stage, but I was only part funny: I was still looking for the missing piece.

Room 1412 at the Belmont Plaza Hotel was more like a cubicle than a room—there was a bed, a couch, a chest of drawers, and . . . that was it. You couldn’t go to the john without bruising your shin. Sonny and I were visiting with Dean, who was fresh from a not-so-hot date.

“She had a roommate,” he said, rolling his eyes. “Where the hell can a fella get laid in peace and quiet in this damn town?”

He poured himself a Scotch to calm down, then gave us a look. “You’re not gonna let me drink this all by myself, are you?”

Hot cocoa was about the strongest thing I’d had at that point in my life, but I gamely accepted a bathroom tumbler half-filled with what smelled like cleaning fluid. I even pretended to take a sip or two as Dean put some 78s on his record player and the three of us proceeded to get into an all-night bull session. To the sounds of Billie Holiday, Tommy Dorsey, Benny Goodman, and Louis Armstrong, we sat and shot the breeze till all hours—or, I should say, one of us did. After Sonny nodded off, I just sat in awe as Dean held forth.