Death at the President's Lodging

Read Death at the President's Lodging Online

Authors: Michael Innes

Tags: #Classic British detective mystery, #Mystery & Detective

- Copyright & Information

- About the Author

- Author's Note

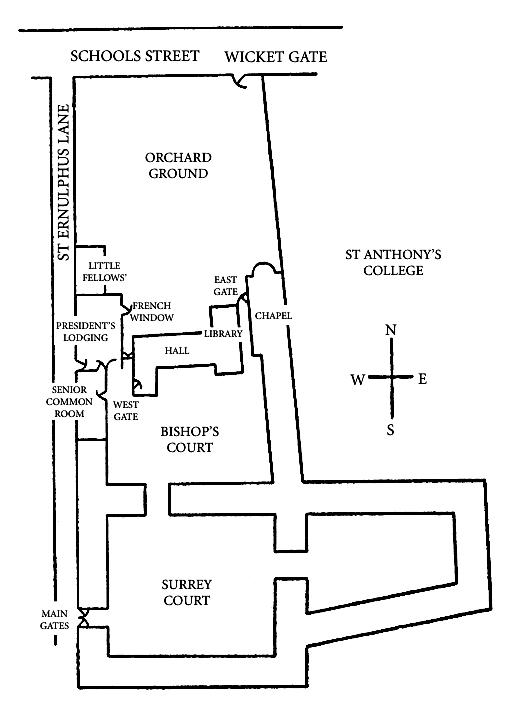

- St. Anthony's College - Location Map

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

- 6

- 7

- 8

- 9

- 10

- 11

- 12

- 13

- 14

- 15

- 16

- 17

- 18

- Works by Michael Innes

- Inspector (later, Sir John) Appleby Series

- Honeybath Series

- Synopses (Both Series & 'Stand-alone' Titles)

Death at the President's Lodging

First published in 1935

Copyright: Michael Innes Literary Management Ltd.; House of Stratus 1935-2009

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form, or by any means (electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise), without the prior permission of the publisher. Any person who does any unauthorised act in relation to this publication may be liable to criminal prosecution and civil claims for damages.

The right of Michael Innes to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted.

This edition published in 2009 by House of Stratus, an imprint of

Stratus Books Ltd., 21 Beeching Park, Kelly Bray,

Cornwall, PL17 8QS, UK.

Typeset by House of Stratus.

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library and the Library of Congress.

ISBN | | EAN | | Edition |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1842327321 | | 9781842327326 | | Paperback |

| 0755118057 | | 9780755118052 | | Pdf |

| 0755119746 | | 9780755119745 | | This Edition |

This is a fictional work and all characters are drawn from the author’s imagination.

Any resemblance or similarities to persons either living or dead are entirely coincidental.

www.houseofstratus.com

Michael Innes is the pseudonym of John Innes Mackintosh Stewart, who was born in Edinburgh in 1906. His father was Director of Education and as was fitting the young Stewart attended Edinburgh Academy before going up to Oriel, Oxford where he obtained a first class degree in English.

After a short interlude travelling with AJP Taylor in Austria, he embarked on an edition of

Florio’s

translation of

Montaigne’s Essays

and also took up a post teaching English at Leeds University.

By 1935 he was married, Professor of English at the University of Adelaide in Australia, and had completed his first detective novel,

Death at the President’s Lodging

. This was an immediate success and part of a long running series centred on his character Inspector Appleby. A second novel, Hamlet Revenge, soon followed and overall he managed over fifty under the Innes banner during his career.

After returning to the UK in 1946 he took up a post with Queen’s University, Belfast before finally settling as Tutor in English at Christ Church, Oxford. His writing continued and he published a series of novels under his own name, along with short stories and some major academic contributions, including a major section on modern writers for the

Oxford History of English Literature

.

Whilst not wanting to leave his beloved Oxford permanently, he managed to fit in to his busy schedule a visiting Professorship at the University of Washington and was also honoured by other Universities in the UK.

His wife Margaret, whom he had met and married whilst at Leeds in 1932, had practised medicine in Australia and later in Oxford, died in 1979. They had five children, one of whom (Angus) is also a writer. Stewart himself died in November 1994 in a nursing home in Surrey.

The senior members of Oxford and Cambridge colleges are undoubtedly among the most moral and level-headed of men. They do nothing aberrant; they do nothing rashly or in haste. Their conventional associations are with learning, unworldliness, absence of mind, and endearing and always innocent foible. They are, as Ben Jonson would have said, persons such as comedy would choose; it is much easier to give them a shove into the humorous than a twist into the melodramatic; they prove peculiarly resistive to the slightly rummy psychology that most detective-stories require. And this is a pity if only because their habitat – the material structure in which they talk, eat and sleep – offers such a capital frame for the quiddities and wiliebeguilies of the craft.

Fortunately, there is one spot of English ground on which these reasonable and virtuous men go sadly to pieces – on which they exhibit all those symptoms of irritability, impatience, passion and uncharitableness which make smooth the path of the novelist. It is notorious that when your Oxford or Cambridge man goes not “up” nor “down” but “across” – when he goes, in fact, from Oxford to Cambridge or from Cambridge to Oxford – he must traverse a region strangely antipathetic to the true academic calm. This region is situated, by a mysterious dispensation, almost half-way between the two ancient seats of learning – hard by the otherwise blameless environs of Bletchley. The more facile type of scientific mind, accustomed to canvass immediately obvious physical circumstances, has formerly pointed by way of explanation of this fact to certain deficiencies in the economy of Bletchley Junction. One had to wait there so long (in effect the argument ran) and with so little of solid material comfort – that who wouldn’t be a bit upset?

But all that is of the past; when I last sped through the Junction it seemed a little paradise; and, anyway, my literary temper is for more metaphysical explanations. I prefer to think that midway between the strong polarities of Athens and Thebes the ether is troubled; the air, to a scholar, nothing sweet and nimble. And I have fancied that if those Oxford clerks who centuries ago attempted a secession had gone to Bletchley there might have arisen the university – or at least the college – I wanted for this story… Anyone who takes down a map when reading Chapter X will see that I have acted on my fancy. St Anthony’s, a fictitious college, is part too of a fictitious university. And its Fellows are fantasy all – without substance and without (forbearing Literary reader!) any mantle of imaginative truth to cover their nakedness. Here are ghosts; here is a purely speculative scene of things.

An academic life, Dr Johnson observed, puts one little in the way of extraordinary casualties. This was not the experience of the Fellows and scholars of St Anthony’s College when they awoke one raw November morning to find their President, Josiah Umpleby, murdered in the night. The crime was at once intriguing and bizarre, efficient and theatrical. It was efficient because nobody knew who had committed it. And it was theatrical because of a macabre and unnecessary act of fantasy with which the criminal, it was quickly rumoured, had accompanied his deed.

The college hummed. If Dr Umpleby had shot himself, decent manners would have demanded reticence and the suppression of overt curiosity all round. But murder, and mysterious murder at that, was felt almost at once to license open excitement and speculation. By ten o’clock on the morning following the event it would have been obvious to the most abstracted don, accustomed to amble through the courts with his eye turned in upon the problem of the historical Socrates, that the quiet of St Anthony’s had been rudely upset. The great gates of the college were shut; all who came or went suffered the unfamiliar ordeal of scrutiny by the senior porter and a uniformed sergeant of police. From the north window of the library another uniformed figure could be glimpsed guarding the closely curtained windows of the President’s study. The many staircases by which the medieval university contrived to postpone the institution of the corridor were lively with the athletic tread of undergraduates, bounding up and down to discuss the catastrophe with friends. Shortly before eleven o’clock a sheet of notepaper – unobtrusive, but displayed contrary to custom outside the college – informed undergraduates from elsewhere that no lectures would be held in St Anthony’s that day. By noon the local papers had their posters on the streets – and in no other town would they have read as discreetly as they did:

Sudden Death of the President of St Anthony’s

. For in the papers themselves the fact was stated: Dr Umpleby had been shot – it was suspected deliberately and by an unknown hand. Throughout the afternoon a little knot of lounging townsfolk, idly gathered on the further side of St Ernulphus Lane, satisfied their curiosity by staring up at the long row of grey-mullioned, flat-arched Tudor windows behind which so intriguing a local tragedy lay. And local tragedy meanwhile was becoming national news. By four-thirty hundreds of thousands of people in Pimlico, in Bow, in Clerkenwell, in the mushroom suburbs of outer London and the hidden warrens of Westminster, were adding a new name to their knowledge of a very remote university town. The later editions put this public on a level with the local loungers, for the same long line of Tudor windows stretched in photographic perspective across the front page. By seven o’clock quadruple supplies of these metropolitanly-keyed news-sheets were being feverishly unloaded within hail of St Anthony’s itself. The cloistral repose of the college was shattered indeed.