Death in a Promised Land (13 page)

Read Death in a Promised Land Online

Authors: Scott Ellsworth

Victim. Walter White, of the NAACP, reported: “One story was told to me by an eyewitness of five colored men trapped in a burning house. Four were burned to death. A fifth attempted to flee, was shot to death as he emerged from the burning structure, and his body was thrown back into the flames.”

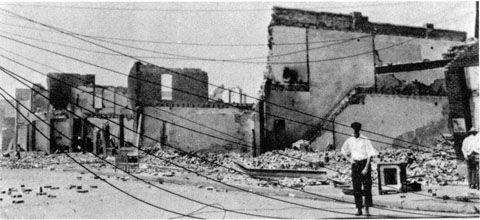

Courtesy of the Metropolltan Tulsa Chrmbef of Commerce

Smoldering dreams.

Courtesy of the Metropolitan Tulsa Chamber of Commerce

O. T. Johnson, Commandant of the Tulsa Citadel of the Salvation Army, stated that on Wednesday and Thursday, the Salvation Army fed thirty-seven Negroes employed as grave diggers, and twenty on Friday and Saturday. During the first two days these men dug 120 graves in each of which a dead Negro was buried. No coffins were used. The bodies were dumped into the holes and covered with dirt. Added to the number accounted for were numbers of others—men, women and children—who were incinerated in the burning houses in the Negro settlement. One story was told to me by an eye-witness of five colored men trapped in a burning house. Four burned to death. A fifth attempted to flee, was shot to death as he emerged from the burning structure, and his body was thrown back into the flames.

42

Ross T. Warner and Henry Whitlow have stated that they saw corpses piled onto trucks which were driven away. Warner stated that he saw at least thirty dead blacks transported in that fashion. It has also been reported by some that dead bodies were dumped into the Arkansas River. Certain city officials and physicians, however, stated in the 1940s that “all those who were killed were given decent burials.”

43

Furthermore, it should be noted that the estimates of official and semi-official groups of the riot fatalities do not necessarily agree. The estimate of the Department of Health’s Bureau of Vital Statistics was that 10 whites and 26 blacks had died in the violence. Estimates

in

Red Cross records—not necessarily its own estimate—on the other hand, ran as high as 300 deaths.

44

Finally, it should be noted that not everyone has agreed that more blacks died in the race riot than whites. W. D. Williams has disputed this assumption, citing as evidence the large number of whites which he saw get shot by black snipers as they attempted to invade “Deep Greenwood.” The Oklahoma City

Black Dispatch

of June 10, 1921, reported that it had received a letter from “a prominent Negro in the city of Tulsa” who stated that “from what he could learn on the ground, about one hundred were killed, equally divided between the two races.”

45

The amount of property lost due to the riot is likewise an elusive quantity. The most common estimate for the amount of real property lost was originally the estimate of the Tulsa Real Estate Exchange. It estimated the loss at about $1.5 million, one third of the total being in the (black) business district. The Exchange also estimated personal property loss at about $750,000. When considering these estimates, however, it is important to recall that the Exchange temporarily approved the designs of the City Commission and others to relocate part of Tulsa’s black community and to use that land for a new train station. Estimates in Red Cross records revealed that 1,115 residences had been destroyed during the riot, and that another 314 houses were looted but not burned. The Tulsa

World

reported that some 338 people suffered losses of real estate, 82 of whom were black.

46

Another source of evidence for property loss are the claims which were filed against the City of Tulsa for losses due to the riot. The minutes of the Tulsa City Commission meetings from June 14,1921, to June 6,1922, reveal that in excess of $1.8 million in claims against the city were filed with—and subsequently disallowed by—the city commissioners.

47

It has also been stated that by July 30, 1921, more than 1,400 law suits for losses upward of $4 million had been filed.

48

The claims filed against the city ranged from under $25 to over $150,000. Emma Gurley, a black woman whose family owned the Gurley Hotel (the Gurley building), filed a claim for its loss in excess of $150,000. Loula T. Williams filed a claim for over $100,000 for the destruction of the Dreamland Theatre and the Williams building. R. G. Dunn and Company reportedly lost some $250,000 in goods. Other large losses included the newly constructed Mount Zion Baptist Church (reportedly built at a cost of $85,000), and the offices of both of Tulsa’s black newspapers, the Tulsa

Star

and the Oklahoma

Sun.

49

The results of the various surveys which were taken by the Red Cross are yet another source of information of the volume of property destruction. As ambiguous as the results were, they reported that one week after the riot, some 5,366 persons had been, to quote Loren L. Gill, “more or less seriously affected by the riot.”

50

Chapter 4

Law, Order,

and the Politics

of Relief

I

The aftermath of the riot provides us with a valuable view of the interworkings of power, race relations, and racial ideologies in Tulsa. The various responses to the riot revealed both humanitarianism and greed, mutual aid and exploitation. “Relief” efforts were in some cases honest, while in many others were but a guise for further abuse. The characters were many.

The first problem faced by black Tulsans after the riot was a question of getting free. Roughly one-half of the city’s black population was forcibly interned under armed guards—at Convention Hall, in public buildings downtown, at the baseball park, and at the fairgrounds. James T. West, a teacher at the Booker T. Washington School, reported that “people were herded in like cattle” into the Convention Hall, and that “the sick and wounded were dumped in front of the building and remained without attention for hours.” At least one black man was shot in front of this large auditorium on Brady Street. Other blacks had a grand tour of imprisonment. Although he was interned at Convention Hall first, Jack Thomas was taken to a Catholic Church, then to the fairgrounds, and finally to a Methodist Church. By June 2, all black Tulsans who were interned—over 4,000—had been moved to the fairgrounds.

1

There, they were held under armed sentries and “sheltered” in the cattle and hog pens. Food, clothing, and some bedding were given out on June 1 and 2. Apparently the physical condition of the prisoners generated concern among doctors, as vaccinations for smallpox, tetanus, and typhoid were administered to some 1,800 people at the camp during its first few days of existence. Black men did road repair work around the camp under the direction of the National Guard.

2

At first, black Tulsans were allowed to leave the camp only if a white person would come and vouch for them, a system designed to allow only those blacks who were employed by whites to be released immediately. Generally, any white employer could secure the release of a black employee by identifying that person and promising that he or she would be kept “indoors or at the scene of their labor.” There were, of course, some exceptions. J. C. Latimer, a black architect and contractor who was interned, claimed that he did not know any whites since he was self-employed. He later stated that a white man lied to the authorities and claimed him as his brother-in-law to gain his release. A few black Tulsans such as Dr. R. T. Bridgewater, an assistant county physician whose home had been burned by whites, worked outside of the camp during the day and returned to it at night to sleep for at least a short period. Most of the imprisoned citizens, once they secured their release, left for good. The 4,000 plus of June 2 dwindled to 450 by June 7. Eight days later, the fairgrounds were empty.

3

In addition to the internment camps, black Tulsans faced other restrictions. While on the streets, they were required to wear or carry a green card with the words “Police Protection” printed on one side, and various other data recorded on the other, including the person’s name, address, and employer. It has been reported that “any black found on the street without a green card properly filled out was arrested and sent back to the detention camp.” Black Tulsans had to carry these cards, which had been paid for by the City Commission and the Chamber of Commerce, until July 7.

4

Blacks were not allowed to purchase or possess firearms for a period of several weeks. On June 6 an order was issued which prohibited the use of servants’ quarters in white districts by blacks “other than those employed regularly on the premises” prior to the riot. Theodore Baugham, black editor of the

Oklahoma Sun,

“succeeded in getting out a little daily paper,” which included lists of people trying to locate their loved ones. However, it is highly doubtful that Baugham was in complete control of the editorial policy of this paper. The June 7 report of the Chamber of Commerce’s Executive Welfare Committee reported that “a negro publication resumed to quiet the negroes,” and Chamber records showed a receipt for a bill to pay for a paper which was “used as a medium to keep the negroes in form [sic] during the few days immediately following the riot.” Baugham’s

Oklahoma Sun

and A. J. Smitherman’s Tulsa

Star

—both of whose offices were destroyed by the white rioters—were blamed by whites for causing the riot.

5

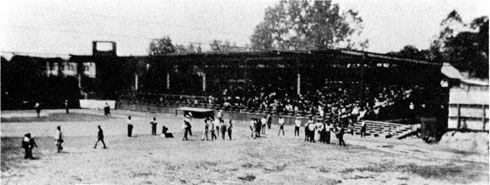

Internment at McNulty baseball park.

Courtesy of the McFarlin Library University of Tulsa

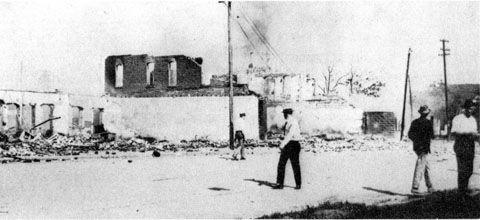

White Tulsans roamed the streets while blacks were imprisoned.

Courtesy of the McFarlin Library, University of Tulsa