Death in a Promised Land (19 page)

Read Death in a Promised Land Online

Authors: Scott Ellsworth

It should be pointed out that white Tulsans are hardly alone in this endeavor to “remember” their history, in Ralph Ellison’s words, as that which they “would have liked to have been.”

15

Rather, it is a characteristic of the oral historical tradition of most white Americans. That an institution as brutal as black slavery has been romanticized so often over the years is in itself a statement about the psychological needs of most white Americans in confronting—or rather, not confronting—their past.

Any similarities between the black and white oral traditions of the riot in Tulsa are far outweighed by their differences. Among black Tulsans, as well as among white Tulsans, the folklore of the event decades later includes both sober renditions and fantastical accounts of what transpired, and at least one folktale about the riot—one of which concerns “Peg Leg” Taylor, who is remembered by some for his work with black youth in Tulsa—has been collected and published. But unlike their white brethren, most black Tulsans who were involved in the riot have

not

been reluctant to discuss their experiences. This is because for many black Tulsans, the riot, and particularly the rebuilding of their community, is an issue of pride. Fifty years after the terrible spring of 1921, W. D. Williams—the young Bill Williams in the Prelude—had a message for young black Tulsans: “They must remember that it was pride that started the riot, it was pride that fought the riot, it was pride that rebuilt after the riot, and if the same pride can again be captured among the younger Blacks, when new ideals with a good educational background, with a mind for business, ‘Little Africa’ can rise again as the Black Mecca of the southwest. But it is up to the young people.” For others the memory of the riot has proved to be hardly an ennobling challenge. A black police officer related that his uncle, who had lived through the riot, still in 1978 kept a gun and ammunition in case it should happen again.

16

It has been said in the city, by both blacks and whites, that the story of the riot has been “hushed up,” and in fact during the 1950s and 1960s black civil rights leaders used the threat of “bringing up” the riot as leverage in negotiations with white leaders in Tulsa. Indeed, the most important factor seems to be what part of Tulsa one lives in. The Oklahoma

Eagle,

which has for many years been Tulsa’s black newspaper, appears to have had no aversion to mentioning the riot over the decades, and in 1971 over two hundred black Tulsans commemorated the event with a ceremony. No such ceremony took place in white Tulsa that year, during which the Tulsa

Tribune

carried what was probably the first in-depth article on the riot since the 1920s. “For fifty years the

Tribune

did not rehash the story,” this article concluded, “but the week of the 50th anniversary seems a natural time to relate just what did happen when a city got out of hand.” The article made no mention of the role which the 1921

Tribune

played in causing the riot.

17

If the story has been suppressed, one reason would have to do with the very history of the city itself. Socially and politically prominent white Tulsans have always been especially sensitive about the city’s image, a heritage dating from the early twentieth century when trainloads of “Tulsa Boosters” fanned out across the nation, trying to win new immigrants and convince people that Oklahoma was not a no man’s land, but that young, beautiful Tulsa was a city bound for glory. If the national image of the city was brightened by these efforts, it was set back in the 1930s with the state’s dust storms and migrants streaming west. Today, as Tulsa’s claim to being the “Oil Capital of the World” grows pretentious, some neo-boosters still bill Tulsa as “America’s Most Beautiful City,” an appellation given by

Reader’s Digest

in the 1950s.

18

The race riot is, for some, a blot on the city’s history and something not to be discussed, much less proclaimed.

A condition peculiar to but one American city? Hardly. Like the well-distributed history of racial violence in the United States, a segregation of memory exists in every part of the nation. It shall continue to do so as long as the injustice which has bred it continues.

IV

Beyond Tulsa, the immediate significance of the riot was perhaps greatest to the young state of Oklahoma. Of his youth in Oklahoma City, within one hundred miles of Tulsa, Ralph Ellison has written:

We had a Negro church and a segregated school, a few lodges and fraternal organizations, and beyond those was the great white world. We were pushed off to what seemed the least desirable side of the city (but which years later was found to contain one of the state’s richest pools of oil), and our system of justice was based upon Texas law, yet there was an optimism within the Negro community and a sense of possibility which, despite our awareness of limitation (dramatized so brutally in the Tulsa race riot of 1921), transcended all of this.

19

In the aftermath of the Tulsa race riot, black Oklahomans employed their own resources, and in doing so, they have endured.

Yet, the event was not denied. If the early history of Oklahoma reveals a greater measure of black freedom and opportunity than the rest of the nation, then the Tulsa race riot—along with the Grandfather Clause, the increased lynchings of blacks, and the rise of Jim Crow—was a capstone to a movement to suppress any uniqueness in race relations which the young state had.

By the spring of 1921, Oklahoma had truly entered the Union.

Epilogue

Notes on the

Subsequent History of

“Deep Greenwood”

The rebuilding of black Tulsa after the riot, particularly that of “Deep Greenwood,” is a story of almost as great importance as the riot itself. Perhaps more than anything else, this rebuilding was a testament to the courage and stamina of Tulsa’s black pioneers in their struggle for freedom.

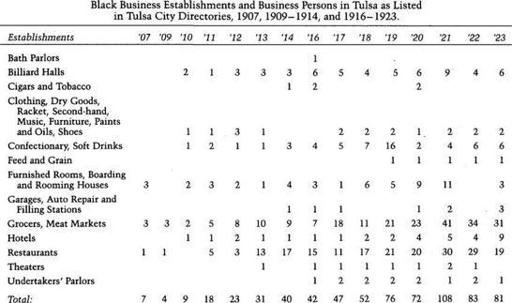

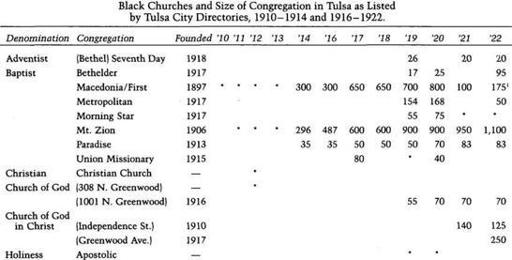

Many of the buildings along the first block of Greenwood Avenue running north from Archer Street were rebuilt by the end of 1922. Although the burned-out shells of the pre-riot structures were for the most part torn down, many of the new buildings assumed the form of their predecessors. The 1922 Williams building, for example, bears a great resemblance to its pre-1921 predecessor. Many of these later buildings were constructed, as the original ones had been, with red bricks from a local brickyard located two blocks north on the avenue.

1

“A little over a decade” after the riot, Henry Whitlow has written, “everything was more prosperous than before. Most of these businesses even survived the Depression.” Furthermore, Whitlow tells us that a local Negro Business Directory was published, a Greenwood Chamber of Commerce organized, the National Negro Business League hosted here, and a black entrepreneur by the name of Simon Berry established a black-owned bus system. “Tulsa’s Negro owned and operated business district became known nationally.”

2

Phoenix-like “Deep Greenwood” did not, however, prosper for ever. By the end of World War II the district had begun a downward spiral. Again we turn to Whitlow: “The merchants of south Tulsa found that the dollar from Greenwood was just as green as the south of the tracks dollar. Relations became better ... by the late fifties Greenwood was on the decline.”

3

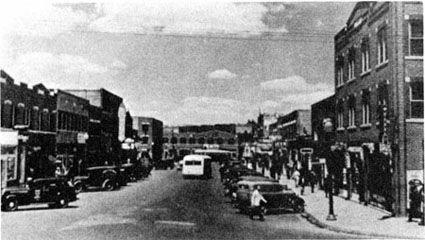

A city reborn: looking north down Greenwood from Archer, 1938.

Courtesy of W. D. Williams

“Greenwood won’t be here any longer,” Clarence Cherry told a journalist in 1971. “In a few years there won’t be any Greenwood.” Seven years later, Cherry’s Shine Parlor is gone. So is the cafe, the nightclub, Jackson’s barber shop, and the rooming house which lined the first block of Greenwood Avenue when Cherry reminisced.

4

In 1978, only two businesses, one of them the Oklahoma

Eagle,

remained. To be certain, the red brick buildings—many of them with cement datestones reading 1922—remain, but they are but empty ghosts of an earlier era.

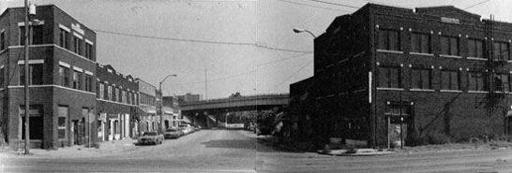

Sitting in his sister’s home in Tulsa, Dr. John Hope Franklin told the author, “There are two ways which whites destroy a black community. One is by building a freeway through it, the other is by changing the zoning laws.” Along with the destruction of the 1921 riot, the first block of “Deep Greenwood” has, at least physically, survived this, too. Franklin’s father helped to defeat the fire ordinance passed by the City Commission after the riot. In recent years, a freeway has cut through the section, but the first block of Greenwood Avenue remains. Few places in the city of Tulsa are as worthy of preservation as this first block of “Deep Greenwood,” a monument to human endurance.

Greenwood and Archer, 1978.

Appendix I

Appendix II