Death in a Promised Land (2 page)

Read Death in a Promised Land Online

Authors: Scott Ellsworth

John, Loula, and Bill Williams, about 1912. Their automobile is a 1911 Nonval k.

Courtesy of W. D. Williams

Then, in 1914, John wanted a bigger garage for his growing automobile business, so the Williamses erected another building, a two-story brick structure, further up Greenwood Avenue. The second story was a twenty-one-room boarding house, and the first floor was to be John’s new garage. John soon found out, however, that there was a city ordinance against having a rooming house above a garage, so he decided to keep working at his old one. John and Loula were then faced with what to do with the empty first floor. The answer came when they read in a newspaper that a theater in Oklahoma City had gone bankrupt, so they purchased its equipment and created the Williams Dreamland Theatre, the first black theater in Tulsa. Silent movies, accompanied by a piano player, were shown and live entertainment was scheduled as well. Loula, assuredly the managerial family member, ran the theater.

In the best American entrepreneurial tradition, the Williams family prospered.

II

On May 31, 1921, sixteen-year-old Bill Williams, together with some of his classmates at the Booker T. Washington High School, was busy decorating a rented hall on Archer Street for the senior prom which was to be held that night. Other students were rehearsing for the graduation exercises not far away on Greenwood Avenue. But before young Williams and his classmates could finish their decorating, an adult came in and told them to go home. They were told that it looked like there might be some racial trouble that evening. Having read that afternoon’s Tulsa

Tribune,

which carried the headline

TO LYNCH NEGRO TONIGHT

,

1

Bill had already sensed this. But rather than go directly home, he headed for the Dreamland Theatre, where his mother was at work. Inside the theater, a man got up on stage and told the audience, “We’re not going to let this happen. We’re going to go downtown and stop this lynching. Close this place down.”

Shortly thereafter, around eight or nine o’clock in the evening, black Tulsans began to gather on Greenwood near Archer, in the heart of their business district. Some of the men had guns. Soon, groups of men drove downtown in cars, and John Williams was one of those who went. Bill wanted to go, too, “to see what was going on,” but his mother would not let him. Instead, the two of them went home, to their apartment above the confectionary. John came home about midnight, after the shooting had begun, and told the family—Loula, Bill, and a young man named Hosea who stayed with them—to go to bed.

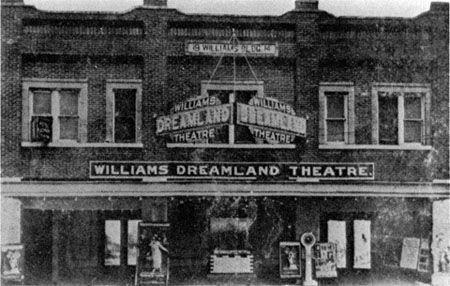

The Dreamland Theatre

.

Courtesy of W. D. Williams

Bill Williams, top left,

ca

. 1921.

Courtesy of W. D. Williams

Loula had been remodeling the family’s apartment shortly before that night, and she had an inside wall removed near the back of the apartment, leaving only the exposed plumbing and ventilation pipes. When Bill Williams woke up the next morning, around five or six, he found his father in the back, resting his 30–30 rifle against the exposed pipes. A repeating shotgun was also at his side. The shooting had begun again. Situated where he was, John could observe goings on both to the west and the south of their building. When white invaders exposed themselves, John would cut loose with his rifle, firing through the window screens. He told his son that he was “defending Greenwood.”

John kept this up for a couple of hours. Before daylight, the whites generally stayed out of Greenwood, but after dawn, their numbers and their determination to enter the black community increased. Hidden as he was, it was some time before the whites found out where John’s rifle fire was coming from, but once they did, they started to riddle the building with gunfire. An airplane flew overhead and, probably anxiously, John fired at it. Finally, he told the family that it was time to leave their home. Too many whites were coming.

The family went downstairs and ran north up Greenwood to an undertaker’s parlor located about eight buildings away. About ten men were already inside, most of them unarmed. John Williams ran across Greenwood Avenue to Hardy’s Pool Hall, where he could get a “right-hand shot” at any whites who were rounding the corner at Greenwood and Archer, or were breaking into his family’s home. In the undertaker’s parlor, Bill went to the back of the building, which bordered the M.K.T. railroad tracks, to see how close the whites were who were coming from the west. The back of the building, which was quite long, had been rented out for “bawdyhouses and that sort of thing,” and behind a partition, he saw a number of people who were intoxicated on opium. Peering out a window, Bill could see whites peeking out from behind railroad cars.

When he got back to the front of the parlor, he found out that his mother had left for her mother’s house on Detroit Avenue. His father then called to him from across the street, “We can’t get Mama now. They probably won’t shoot her. But you come on.” Running low, Bill and Hosea crossed Greenwood. Bill could hear bullets singing down the avenue. A man from the undertaker’s parlor followed, and they went up to the second floor of the pool hall where John positioned himself and his rifle at its front windows. Whites had already begun breaking in and burning on Archer.

The man from the funeral parlor, unknown to Bill, was without a gun and so decided to make the run back to retrieve the shotgun that John had left at the parlor. Dodging bullets, he made it across the street twice again. Although, like John Williams, the man was a good marksman, he could not load the gun properly, so Bill had to show him. The two men held the pool hall position for about an hour before, once again, it was time to go. Whites had broken into buildings on the west side of Greenwood Avenue, directly across from them.

Bill and his father went down the back stairs of the building which housed the pool hall. Bill hesitated, however, because he did not know where Hosea was. His father said, “We’ll split up here, and I’ll meet you down on Pine Street.” His father started walking north along the Midland Valley railroad tracks. A little while later, Bill started walking north, toward Pine, using the alley between Greenwood and Hartford avenues. He had a couple of shotgun shells in his pocket which he threw away. He had gone about two blocks when he was met by three armed whites. One of them said, “Hold up your hands, nigger.”

One day later, after having spent the night at the home of a white projectionist who worked at the Dreamland and who secured his release from Convention Hall, Bill Williams was reunited with his mother and father. Together, they went back to Greenwood.

III

They found the business district to be a burned-out shell. Their home—the building at Greenwood and Archer which also housed their confectionary—had been looted and burned. Their theater, too, was but bricks and ashes.

2

What had happened? Overnight, over one thousand homes occupied by blacks had been destroyed in Tulsa. The Greenwood business district had been put to the torch. The city had been placed under martial law. Many, both black and white, had died or were wounded.

IV

The history of the Tulsa race riot is but one chapter in the troubled history of racial violence in America. In terms of density of destruction and ratio of casualties to population, it has probably not been equaled by any riot in the United States in this century. Nevertheless, the Tulsa race riot is not a lone aberration rudely jutting out of a saner, calmer past. Events similar to the one described here are part of the histories of Boston, Providence, New York, Philadelphia, Washington, Atlanta, New Orleans, Detroit, Chicago, Duluth, Omaha, Los Angeles, and scores of other cities and towns in every part of the nation. They were a part of the American scene in the 1830s as well as in one city in the late spring of 1921.

3

The story of Tulsa is very much a story of America.

“What the future holds regarding race relations in America nobody knows,” wrote historian William Tuttle in 1970, “but one thing is evident. The optimist cannot take solace in the past.”

4

The concerned can, however, learn from it. But to do so, it is necessary to lift the Tulsa race riot from its distorting setting as a singular, “dramatic event,” and view it within the context of the various forces which shaped both Tulsa and America in 1921, and which, indeed, shape them both today.

Chapter 1

Boom

Cities

I

Tulsa was a boom city in a boom state. Between 1890 and 1920, the population of the land which became the state of Oklahoma increased seven and one-half times; the total population in 1920 was over two million. Thirteen other states and territories, primarily in the West, more than doubled their populations during this period, but Oklahoma’s rate of increase was by far the largest. And of these states, only Texas, with its much larger land area, surpassed Oklahoma in the number of people added to her population during these decades. By far, the greater part of Oklahoma’s population boom was due to immigration. But unlike the forced immigration of Native Americans which began in the 1830s, the new immigrants’ move was a matter of choice. Most of them came between 1890 and 1910, an era marked by land runs and statehood (1907).

1

They came for a variety of reasons and from a variety of places, but for many Oklahoma was a place to start life anew.

Tulsa’s growth during the first years of the twentieth century was even more dramatic. Located along a bend in the Arkansas River in a verdant area where the oak-laden foothills of the Ozarks slowly melt westward into the treeless Great Plains, it had been a Creek settlement known as “Tulsey Town” during the latter part of the nineteenth century. The first permanent white settlers did not arrive until the early 1880s; Tulsa’s population in 1900 was estimated at 1,390. During the next two decades, the city’s population skyrocketed. In 1910, the Census Bureau listed Tulsa’s population at 18,182; in 1920 at 72,075. In that latter census, Tulsa ranked as the ninety-seventh largest city in the United States, comparable in size to such cities as San Diego; Wichita; Wilkes-Barre, Pennsylvania; and Troy, New York. City directory estimates, it should be added, were higher than those of the federal government, and the 1921 directory recorded Tulsa’s population as 98,874.

2

The primary reason for Tulsa’s rapid growth was oil, and as one writer in the 1920s remarked, “the story of Tulsa is the story of oil.” Petroleum had been discovered in 1897 near Bartlesville, Indian Territory, some fifty miles north of Tulsa, and in 1901 the Southwest oil boom seriously got under way with two noted petroleum discoveries: the Spindletop strike near Beaumont, Texas; and the strike at Red Fork, Indian Territory.

3