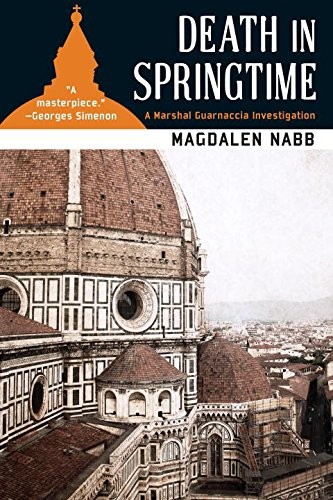

Death in Springtime

DEATH IN SPRINGTIME

Also by the author

DEATH OF AN ENGLISHMAN

DEATH OF A DUTCHMAN

DEATH IN AUTUMN

THE MARSHAL AND THE MURDERER

THE MARSHAL AND THE MADWOMAN

THE MARSHAL'S OWN CASE

THE MARSHAL MAKES HIS REPORT

THE MARSHAL AT THE VILLA TORRINI

THE MONSTER OF FLORENCE

PROPERTY OF BLOOD

SOME BITTER TASTE

THE INNOCENT

with Paolo Vagheggi

THE PROSECUTOR

DEATH IN SPRINGTIME

Magdalen Nabb

Copyright © 1983 by Magdelen Nabb

and 1999 by Diogenes Verlag AG Zurich

Pubished in the United States in 2005 by

Soho Press, Inc.

853 Broadway

New York, NY 10003

All rights reserved.

Library of Congress Cataloging in Publication Data

Nabb, Magdalen, 1947-

Death in springtime / Magdalen Nabb

p. cm.

ISBN-13: 978-1-56947-415-0

ISBN-10: 1-56947-415-X

1. Guarnaccia, Marshal (Ficticious character)-Fiction. 2.Young women-Crimes against-Fiction. 3. Police-Italy-Florence-Fiction. 4. Americans-Italy-Fiction. 5. Florence (Italy)-Fiction. 6. Kidnapping-Fiction. I. Tide.

PR6064.A18D37 2005

823'.914-dc22 2005049045

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

Contents

Dear friend and fellow author,

What a pleasure it is to wander with you through the streets of Florence, with their carabinieri, working people, trattorie, even their noisy tourists. It is all so alive: its sounds audible, its smells as perceptible as the light morning mist above the Arno's swift current; and then up into the foothills, where the Sardinian shepherds, their traditions and the almost unchanged rhythm of their lifestyle, are just as skilfully portrayed. What wouldn't one give to taste one of their ricotta cheeses!

You have managed to absorb it all and to depict it vividly, whether it is the various ranks of the carabinieri, and of course the ineffable Substitute Prosecutor, or the trattorie in the early morning hours. There is never a false note. You even capture that shimmer in the air which is so peculiar to this city and to the still untamed countryside close at hand.

This is a novel to be savoured, even more than its two predecessors. It is the first time I have seen the theme of kidnapping treated so simply and so plausibly. Although the cast of characters is large, they are so well etched in a few words that their comings and goings are easily followed.

Bravissimo! You have more than fulfilled your promise.

Lausanne, April 1983

'It can't be. Today's the first of March . . .'

'But it is, look!'

'Must be some sort of seed blowing on the wind.'

'What wind? I tell you it's snow!'

The entire population of Florence had woken up blinking in amazement and consternation. Shutters had banged open and people had exclaimed to one another across courtyards and narrrow streets.

'It's snowing!'

Only once in the last fifteen years or so had it snowed in the city, and that had been in the middle of winter when an icy blast from the Russian Steppes had swept across the whole Italian peninsula, covering even the motorways with a paralysing blanket of white. But today was the first of March. And to make it even more incredible the weather during the past two weeks had been exceptionally warm, and the first tourists, always the ones from Germany, had been going about in light-coloured clothing, the women baring plump white arms to the feverish February sun. The Florentines themselves never shed their green loden overcoats until the end of April, but even so, a few people had been sufficiently deceived to put the first potted geraniums out on their windowsills, and in the mild evenings brown slatted shutters had been left half-open to reveal bands of yellow light and silhouetted figures looking out to watch the goings on in the piazza, giving the impression of a summer night.

Then it had only been the vine- and wheat-growers in the surrounding hills who had complained about the weather. After all, at that time of year it ought to have been raining. Now, to cap everything, it was snowing, and people couldn't have been more surprised if carnival confetti had been falling out of the sky.

The eight o'clock rush hour had started under the stare of a pale cold light. Toddlers pressed their noses against windows high up in lighted apartments making patches of steam which they rubbed away or drew in with one finger.

The sky was so blank that the snow seemed to be falling down from nowhere, appearing between the great stone buildings, big wet flakes that floated into the road and vanished, leaving only a mottled damp strip between the dry pavements and gutters which were sheltered by the overhanging eaves.

People queuing for the bus in the tiny Piazza San Felice turned up their collars and looked anxiously at the sky, wondering if perhaps they should have worn a scarf or gloves. But it wasn't even cold! There was no explanation for it at all. Opposite them, Marshal Guarnaccia of The Carabinieri was standing on the corner as he often did after having a coffee at the bar. He stood on the edge of a group of gossiping mothers who had just given their children over to the care of a nun who ushered them into the infant school next to the church, and he alone, although he turned up the collar of his black greatcoat with an automatic gesture, was not staring at the snow but at the trat-toria across the street. Over there the lights were on in clusters of hanging globes, and the owner's son, wrapped in a dirty white apron, was sweeping up in a desultory fashion, scattering sawdust just behind the glass door, staring out vacantly at the weather all the while. The boy, thin and pimply with a shock of black hair, was only sixteen, but already Marshal Guarnaccia had caught sight of him injecting himself on the steps of Santo Spirito church, sitting on the edge of the usual huddled group and glancing furtively about him in a way that only very new users do.

The number 15 bus came along and stopped, blocking the Marshall's view. The bus, too, was lit up, and every face along its length was gazing out as if hypnotized by the big flakes floating slowly down past the windows. The Marshal, preoccupied with the problem of what, if anything, to say to the boy's father, and with a case that was coming up in Appeal Court in a few days, continued to ignore the snow, even though, as a Sicilian, he might well have been more amazed by it than the Florentines. Nevertheless, he was destined to remember it only too well and to be driven to exasperation by witness after witness repeating the same infuriating phrase with the same apologetic smile:

'I didn't notice anything, to be honest. I don't know if you remember but it was snowing that morning . . . Just fancy, snowing in the centre of Florence, and in March, too . . .'

The bus signalled and moved off. The boy had parked his broom and disappeared into the back of the trattoria. The first big logs had been put on to the fire where they roasted the meat and long flames were beginning to lick at them. Above the high building, blue woodsmoke drifted about uncertainly among the loose snowflakes, adding its sweet smell to the prevailing morning odours of coffee and exhaust fumes.

The Marshal looked at his watch. There was no time to do anything about the boy now if he was going to visit the prison as he wanted to. In any case it might be better to try talking to the lad himself first and leave the father out of it. And then it was more than likely that either or both of them would tell him to mind his own business. He sighed and made to cross the road. A car was coming along from his left and signalling intermittently in the face of the one-way traffic coming relentlessly towards it up Via Romana. Two girls were in the front and someone in the back was leaning forward between them, evidently trying to give directions from behind an enormous map. More tourists. The invasion got earlier and earlier every year, making it impossible to go about normal business in the overcrowded narrow streets. Only the day before somebody had written to the editor of the

Nazione

suggesting ruefully that the mayor should provide a campsite somewhere out in the hills for the Florentines since there was no longer any room for them in their own city. However profitable tourism was supposed to be, they resented the annual invasion.

It was early, too, for the Sardinian bagpipers who didn't often appear between Christmas and Easter. But as the Marshal walked over towards Piazza Pitti and his Station he saw one coming towards him, enveloped in a long black shepherd's cloak, the white sheepskin airbag tucked under his arm. He was playing disjointedly and rather discordantly and no one took any notice of him or gave him any money. The Marshal automatically glanced across at the other side of the street expecting to see the second piper who played the melody on a small, oboe-like pipe, but he was nowhere in sight. Probably gone into one of the shops to beg. There was no time to linger and the Marshal went up the sloping forecourt of the Pitti Palace, squeezing his decidedly overweight bulk between the closely parked cars, and disappearing under the stone archway on the left.

When he poked his head into the office to say that he was taking the van he added, as an afterthought: 'It's snowing . . .'

Just outside Florence in the Chianti hills it snowed harder and the sky remained low and white all day. The loose flakes melted quickly on the stony, ochre-coloured roads but managed to cling to the newly sprouting wheat. The stiff little leaves on the olive trees each held a wafer of snow. There was no frost and evidently no danger of it, and the country people looking out of the barred windows of castles, villas and farmhouses regarded this unexpected but harmless weather with scant interest, only remarking with a doubtful look at the pale sky:

'It's rain we need . . .'

But the snow went on falling throughout the day. In the early evening it turned to sleet and by midnight it was raining hard, filling dark ditches, furrows and potholes and rinsing the small trees free of their burden. At four in the morning the lights of a van shone through the heavy rain, illuminating a stretch of the unmade road that connected the hilltop villages of Taverna and Pontino. The van stopped and its lights went out for a few moments before it backed up, turned and drove away showing blurred red tail-lights.

When the noise of the engine died away, slurred footsteps could be heard moving forward in the darkness. When they passed the gate of a farmhouse a dog began to bark but no light went on. The dog lost interest as the steps faded into the distance. At a bend in the road, marking the beginning of Pontino, an icon was framed by a little stone arch. Only the pinpoint of red light and the plastic flowers in a jamjar at its feet were visible. When the footsteps reached the icon they stopped. The tiny red lamp gave off a faint pink light which showed the slight form of a girl who reached out a hand towards the icon and then collapsed, hitting her forehead on one of the jutting stones of its arch. For over an hour the rain beat heavily on the grass, the arch and the crumpled figure, then the girl got to her feet and stumbled on towards the village of Pontino, sometimes wandering off the road, confused by more little red lights that appeared all around her. In the piazza there was one window lit but the girl, instead of making for the light, walked round in circles bumping into trees, benches and lamp posts in the darkness. It was only after some time, and then by accident, that she found herself looking in at the lighted window. The rain beat on her head and swilled down the glass beyond which she saw a blur of flowers. In the middle of the flowers sat a gnome-like figure wearing a large green apron and a striped turban. He was rocking to and fro, apparently crooning to himself while dipping a long wooden painting brush into big pots of brightly coloured paint.

He daubed the paint on to the white daisies in his lap, turning them turquoise, magenta and blue.

Above the daubing figure was a tiny red light and a plaster figure of the Virgin dandling a chipped baby. The flowers in the vase at the foot of the statue were plastic. The painted face of the Virgin stared out of the window with a faint smile as the girl lifted a wet cold hand to tap at the glass.