Delphi (40 page)

Authors: Michael Scott

Cyriac's visit to Delphi was an exception. We have no record of any one else making this journey for over two hundred years after this, until the English mathematician Francis Vernon made his way there on the 26 September 1675, by which time the village of Castri had grown, and the sanctuary of Delphi had sunk further into the ground. In the meantime, despite the difficulty of obtaining access to, and traveling in, the region, the great interest in classical antiquity had continued to grow, particularly in the French and English courts. By the late seventeenth century, the idea that there was much to see, that it was important to see it and if possible own it as well was established. The acquiring of such artifacts was particularly valuable as an instrument of international power politics between royal families and aristocrats. It was in this atmosphere that two famous travelers reached Castri a year after Vernon, on 30 January 1676: the French doctor Jacob Spon and the English naturalist George Wheler, both crucial to the history of the development of archaeology. Spon was the first to use the word “archaeology,” in the preface to his publication about the diverse monuments in Greece. At Delphi, they identified the gymnasium that lay beneath the monastery of the Panagyia (which would later keep a register of all visitors to the area), but otherwise “had to stop there and be satisfied with what we could learn from books of the former wealth and grandeur of the place: for nothing remains now but wretched poverty and all its glory has passed like a dream.”

20

Jacob Spon's thoughts continued in the epigraph to this chapter. He was overwhelmed and sobered that a place as famous and as wonderful as Delphi could disappear. For Spon, Delphi was the ultimate warning about what could occur as the result of human hubris.

Soon after their visit, in 1687, the Venetian assault against the Turks in Athens led to the igniting of the gunpowder store in the Parthenon,

whereupon large sections of the building were destroyed. Yet this did nothing to slow the passion for antiquities, both as possessions for the powerful, and as important windows into the past for those interested in history. In 1734 the Society of Dilettanti was formed in London for aristocrats who had visited Italy and who had, at least according to Horace Walpole, been drunk (preferably in Italy). The discovery of Herculaneum in 1738 and Pompeii in 1748 fanned the flames of interest. In France, there was a craze for Greek inscriptions, not only because they were considered the most useful type of evidence for illustrating history, but also (and perhaps more importantly) because they could be used as meaningful mottoes for medals struck to commemorate the exploits of Louis XIV (for which the Academie des Inscriptions et Belles Lettres had been established in 1701).

21

By 1748, just as Pompeii was being uncovered, the English architects James Stuart and Nicholas Revett found willing ears to their call that “unless exact drawings can be speedily made, all [Athens's] beauteous fabricks, temples, theatres, palaces will drop into oblivion, and Posterity will have to reproach us.” Volume I of their detailed drawings of monuments in Greece was published in 1762, and it was as part of their work that they came to Delphi in 1751. During their stay en route from Thermopylae, they were bewitched by the romantic feel of the natural landscape, but also took time to investigate in among the buildings of the haphazard village of Castri. They found part of the enormous polygonal wall covered in inscriptions that supported the temple terrace (see

plate 2

). The stones of the wall were so large, they lamented, that they were unable to take them away.

22

Some laughed at this newfound love of all things Greek, but many would have agreed with Gavin Hamilton, a dealer in Rome, who (with great advertising aplomb) said in 1779, “Never forget that the most valuable acquisition a man of refined taste can make is a piece of Greek sculpture.” The “gusto Greco” was now in full maturity, fueled also by the crucial writings of the German scholar Johann Joachim Winckelmann in the second half of the eighteenth century on the beauty and importance of Greek sculpture. Although Winckelmann never actually set

foot in Greece, more and more travelers did make the arduous journey to Athens, and a handful made the even more difficult journey to Castri nestled in the Parnassian mountains. Some even went so far as to drink from the water of the Castalian Spring, famed in the surviving literature as the bathing place of the oracular priestess (see

fig. 0.2

). Richard Chandler, on an expedition sanctioned by the Society of the Dilettanti, bathed in the waters in July 1766 and, despite the summer weather, was overwhelmed by the coldness of the water to the extent that he shook so badly he was unable to walk without aid. Returning home, he wrapped himself up, drank large quantities of wine, and began to sweat profusely. Perhaps, he mused, this was what the ancients had taken for the oracular priestess's possession by the god.

23

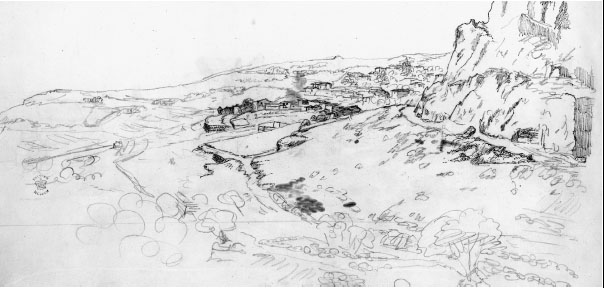

But despite this kind of ancient amusement-park activity, what could Delphi really offer its visitors? Inscriptions were all the rage, and Delphi had many of them to offer. Late eighteenth-century visitors write with glee of finding more inscriptions than they had time to record. But the disappointment felt by Spon and Wheler at the meager remains of what had been, according to the ancient literary sources, one of the most extraordinary sites in the ancient world, continued to pervade visitors' thoughts. As they arrived with their literary texts in handâparticularly Pausanias, who, as indicated above, had written the first tour guide of the sanctuary back in the second century

AD

âDelphi's first modern tourists were continually disappointed in their inability to see the site itself. William Gell's drawing of Castri from 1805 outlines the little that was on view (

fig. 12.1

). As the Swedish priest A. F. Sturtzenbecker put it following his visit in 1784: “Delphi has kept nothing of its former splendour. Everything is lost bar its name.”

24

The beginning of the nineteenth century witnessed a quickening in the pulse of interest in, and travel to, Greece. For the English, this was in part because the Napoleonic Wars had made travel to Italy, the traditional destination for those interested in the ancient world, difficult. Greece was the next best alternative as part of the Grand Tour. “Epidauria” claimed the English naturalist Edward Clarke in 1801, “is a region as easily to be visited as Derbyshire.” At the same time, painting at the beginning of the nineteenth century began explicitly to take its inspiration from the classical landscape as

the

example of the picturesque, and Greece became a kind of idyllic Arcadia mixed with pure fantasy and occasionally accurate depictions of surviving ruins. This longing for the idealized, however, also clashed with an increasing interest in securely identifying ancient sites in the Greek landscape, spurred on by the wider availability of key texts like Pausanias (translated into English for the first time at the end of the eighteenth century). In two campaigns, 1805â1807 and 1809â10, British army officer William Martin Leake, for example, mapped the Greek landscape in meticulous detail, which led to the discovery of sites like the Temple of Bassae in 1812.

25

In response, in 1813, the Society of Friends of the Muses was set up in Greece to help uncover and collect antiquities, assist students, and publish books.

Figure 12.1

. A drawing of Castri/Delphi in the nineteenth century

AD

by William Gell (1805) (© The Trustees of the British Museum)

Yet such an interest in the landscape, among western Europeans, also chimed with, and indeed helped provoke, an increasing interest in

owning, and exporting, its contents. From 1810, the topographers started to lose ground to the collectors, spurred on as the latter were by Elgin's work in bringing the Parthenon marbles to England 1801â1803 and displaying them in a public exhibition in 1807 before they were bought by the British Museum in 1816. It was an act matched by the French, who, in 1833 brought the Luxor Obelisk to the Place de la Concorde in Paris, and by the Bavarian King, who bought the sculptures of the Temple of Aphaia at Aegina in 1811. The overarching feeling was that modern Europe was now worthy of ancient Greece, and thus had the right to take what remained of it.

26

The village of Castri, and ancient Delphi, were not indifferent to this three-pronged European interest to idealize, record, and physically capture/walk off with ancient Greece in the first decades of the nineteenth century. William Gell's paintings, despite his rather desolate drawings, offer Arcadian images of the Castalian fountain, and those of William Walker offer encouraging visions of the site as one in which ancient ruins complement modern structures (

plate 7

). George Hamilton, Earl of Aberdeen and later prime minister, engraved his name on a marble by the Monastery of the Panaghia in 1803 (in the area of the ancient gymnasium). Henry Raikes mapped the topography of the Parnassian landscape and located for the first time the Corycian cave eight hundred meters above Delphi, in 1806 (see

map 3

). Yet the burial of most of the site underneath the village frustrated any real attempt at excavation or removal, despite the fact that Sir William Hamilton, better known for his discovery of Greek vases in Etruria, had persuaded Lord Nelson at the end of the eighteenth century to ship to England a small altar found at Delphi (it now sits in Castle Howard in Yorkshire), persuasion successful perhaps because Hamilton's young wife was also Nelson's mistress.

27

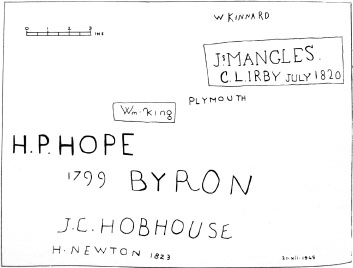

It is difficult to underestimate the myriad ways in which Greece impacted western Europe during the first quarter of the nineteenth century: King Ludwig of Bavaria even claimed he would rather be a citizen of ancient Greece than king of Bavaria. Crucial to understanding this impact is the fact that there was often little agreement (and not less than a pinch of hypocrisy) between its strongest advocates. The Society of Dilettanti actively tried to undermine the authenticity of Elgin and the Parthenon marbles because they were examples of the naturalistic style of sculpture, which the Society detested in comparison to its preferred “Ideal” style. The poet Lord Byron in turn sought to disgrace Elgin for his denuding of Greece (see

Childe Harold's Pilgrimage

;

The Curse of Minerva

1812), caring little for Elgin's stated aim “to improve the arts in England,” preferring instead to honor the glory that was Greece by recreating it in poetry and action. Yet Byron also happily engraved his name on ancient stones at a number of ancient sites, including on a column from the gymnasium at Delphi (

fig. 12.2

).

28

Figure 12.2

. A copy of graffiti found on a column in the gymnasium at Delphi, including the signature of Lord Byron ([La redécouverte de Delphes fig. 28])

Despite this cultural, intellectual, and political storm of which Greece was the centerâbecause of the difficulties of seeing the ancient siteâthe overwhelming feeling was nevertheless of nostalgic sadness and disappointment at the gap between the literary accounts of Delphi's past glory and its meager present. Byron complained bitterly of having to sample a

half a dozen stagnant brooks before finding the Castalian fountain, which he pronounced “ugly.” The artist Louis Dupré complained in 1819 about finding not the “superb Delphi, but the miserable village of Castri.”

29

Yet a larger storm was brewing that would fundamentally affect the future of the site. In 1771, following his travels in Greece, Pierre Augustin Guys, a French merchant turned proto-anthropologist, had published his thoughts on the parallels between ancient and modern Greeks claiming not only to see much connection between them, but also that modern Greeks preserved a simplicity lamentably lost in Western Europe. Even more importantly, his work offered the idea that the modern Greeks were not without hope, that their spirits were dormant, waiting for the right moment to rise up to glory once again. His work won great acclaim with Catherine the Great in Russia, who meddled in Greek politics in the 1770s, persuading the Greeks that Russia would support them if they rose up against the Turks. The putative revolution was a disaster. But it sowed the seeds for European support for the Greek war of independence when it came in 1821. In that war, the heritage of ancient Greece was crucial both as an incitement to revolt, and as a marker for what a newly liberated Greece might achieve.

30