Delphi Complete Works of Oscar Wilde (Illustrated) (37 page)

Read Delphi Complete Works of Oscar Wilde (Illustrated) Online

Authors: OSCAR WILDE

LORD ILLINGWORTH. And in Gerald’s handwriting.

MRS. ARBUTHNOT. It was not to have been sent. It is a letter he wrote to you this morning, before he saw me. But he is sorry now he wrote it, very sorry. You are not to open it. Give it to me.

LORD ILLINGWORTH. It belongs to me.

[Opens it, sits down and reads it slowly. MRS. ARBUTHNOT watches him all the time.]

You have read this letter, I suppose, Rachel?

MRS. ARBUTHNOT. No.

LORD ILLINGWORTH. You know what is in it?

MRS. ARBUTHNOT. Yes!

LORD ILLINGWORTH. I don’t admit for a moment that the boy is right in what he says. I don’t admit that it is any duty of mine to marry you. I deny it entirely. But to get my son back I am ready - yes, I am ready to marry you, Rachel - and to treat you always with the deference and respect due to my wife. I will marry you as soon as you choose. I give you my word of honour.

MRS. ARBUTHNOT. You made that promise to me once before and broke it.

LORD ILLINGWORTH. I will keep it now. And that will show you that

I love my son, at least as much as you love him. For when I marry

you, Rachel, there are some ambitions I shall have to surrender.

High ambitions, too, if any ambition is high.

MRS. ARBUTHNOT. I decline to marry you, Lord Illingworth.

LORD ILLINGWORTH. Are you serious?

MRS. ARBUTHNOT. Yes.

LORD ILLINGWORTH. Do tell me your reasons. They would interest me enormously.

MRS. ARBUTHNOT. I have already explained them to my son.

LORD ILLINGWORTH. I suppose they were intensely sentimental, weren’t they? You women live by your emotions and for them. You have no philosophy of life.

MRS. ARBUTHNOT. You are right. We women live by our emotions and for them. By our passions, and for them, if you will. I have two passions, Lord Illingworth: my love of him, my hate of you. You cannot kill those. They feed each other.

LORD ILLINGWORTH. What sort of love is that which needs to have hate as its brother?

MRS. ARBUTHNOT. It is the sort of love I have for Gerald. Do you think that terrible? Well it is terrible. All love is terrible. All love is a tragedy. I loved you once, Lord Illingworth. Oh, what a tragedy for a woman to have loved you!

LORD ILLINGWORTH. So you really refuse to marry me?

MRS. ARBUTHNOT. Yes.

LORD ILLINGWORTH. Because you hate me?

MRS. ARBUTHNOT. Yes.

LORD ILLINGWORTH. And does my son hate me as you do?

MRS. ARBUTHNOT. No.

LORD ILLINGWORTH. I am glad of that, Rachel.

MRS. ARBUTHNOT. He merely despises you.

LORD ILLINGWORTH. What a pity! What a pity for him, I mean.

MRS. ARBUTHNOT. Don’t be deceived, George. Children begin by loving their parents. After a time they judge them. Rarely if ever do they forgive them.

LORD ILLINGWORTH.

[Reads letter over again, very slowly.]

May I ask by what arguments you made the boy who wrote this letter, this beautiful, passionate letter, believe that you should not marry his father, the father of your own child?

MRS. ARBUTHNOT. It was not I who made him see it. It was another.

LORD ILLINGWORTH. What FIN-DE-SIECLE person?

MRS. ARBUTHNOT. The Puritan, Lord Illingworth.

[A pause.]

LORD ILLINGWORTH.

[Winces, then rises slowly and goes over to table where his hat and gloves are. MRS. ARBUTHNOT is standing close to the table. He picks up one of the gloves, and begins pulling it on.]

There is not much then for me to do here, Rachel?

MRS. ARBUTHNOT. Nothing.

LORD ILLINGWORTH. It is good-bye, is it?

MRS. ARBUTHNOT. For ever, I hope, this time, Lord Illingworth.

LORD ILLINGWORTH. How curious! At this moment you look exactly as you looked the night you left me twenty years ago. You have just the same expression in your mouth. Upon my word, Rachel, no woman ever loved me as you did. Why, you gave yourself to me like a flower, to do anything I liked with. You were the prettiest of playthings, the most fascinating of small romances . . .

[Pulls out watch.]

Quarter to two! Must be strolling back to Hunstanton. Don’t suppose I shall see you there again. I’m sorry, I am, really. It’s been an amusing experience to have met amongst people of one’s own rank, and treated quite seriously too, one’s mistress, and one’s -

[MRS. ARBUTHNOT snatches up glove and strikes LORD ILLINGWORTH across the face with it. LORD ILLINGWORTH starts. He is dazed by the insult of his punishment. Then he controls himself, and goes to window and looks out at his son. Sighs and leaves the room.]

MRS. ARBUTHNOT.

[Falls sobbing on the sofa.]

He would have said it. He would have said it.

[Enter GERALD and HESTER from the garden.]

GERALD. Well, dear mother. You never came out after all. So we have come in to fetch you. Mother, you have not been crying?

[Kneels down beside her.]

MRS. ARBUTHNOT. My boy! My boy! My boy!

[Running her fingers through his hair.]

HESTER.

[Coming over.]

But you have two children now. You’ll let me be your daughter?

MRS. ARBUTHNOT.

[Looking up.]

Would you choose me for a mother?

HESTER. You of all women I have ever known.

[They move towards the door leading into garden with their arms round each other’s waists. GERALD goes to table L.C. for his hat. On turning round he sees LORD ILLINGWORTH’S glove lying on the floor, and picks it up.]

GERALD. Hallo, mother, whose glove is this? You have had a visitor. Who was it?

MRS. ARBUTHNOT.

[Turning round.]

Oh! no one. No one in particular. A man of no importance.

CURTAIN

This tragedy was first written by Wilde in

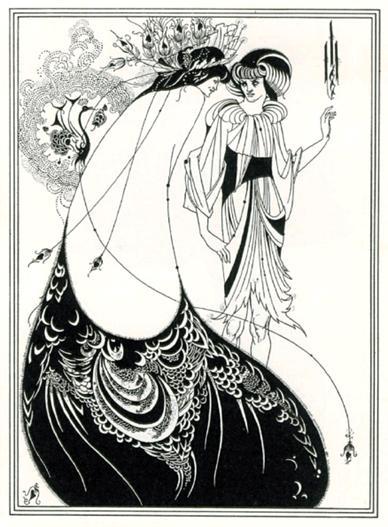

The play tells in one act the Biblical story of Salomé, stepdaughter of the tetrarch Herod Antipas, who, to her stepfather’s dismay, requests the head of John the Baptist on a silver platter as a reward for her dancing.

In 1892 rehearsals began for the play’s debut, for inclusion in Sarah Bernhardt’s London season, though preparations were halted when the Lord Chamberlain’s licensor of plays banned

Salomé

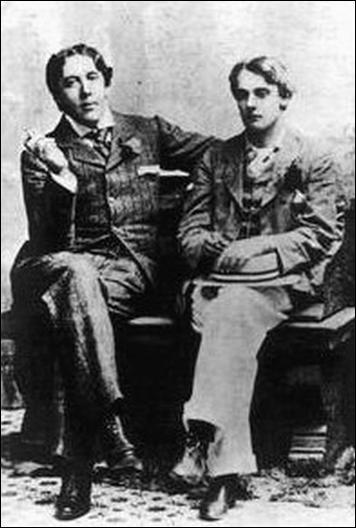

on the basis that it was illegal to depict Biblical characters on the stage. The play was first published in French in February 1893, and the English translation, with illustrations by Aubrey Beardsley, followed in February the following year. Wilde and Douglas had quarrelled over the translation of the text which Wilde felt was very poor due to Douglas’ poor understanding of French, though his lover claimed that the errors were really in Wilde’s original text. Beardsley and the publisher John Lane were also drawn into the argument, though they sided with Wilde. In a gesture of reconciliation, Wilde did the work himself, but dedicated Douglas as the translator rather than having them sharing their names on the title-page.

The play was eventually premiered on 11 February 1896, while Wilde was in prison, in Paris at the Comédie-Parisienne in a staging by Aurélien Lugné-Poë’s theatre group, the Théâtre de l’Œuvre.

Wilde’s interest in Salomé’s image had been stimulated by descriptions of Gustave Moreau’s paintings in Joris-Karl Huysmans’s ‘À rebours’.

A first edition illustration

Oscar Wilde and Douglas in 1893

Maud Allan as Salomé with the head of John the Baptist in an early adaptation the play