Delphi Complete Works of Oscar Wilde (Illustrated) (62 page)

Read Delphi Complete Works of Oscar Wilde (Illustrated) Online

Authors: OSCAR WILDE

MASON. Luncheon is on the table, my Lady!

[MASON goes out.]

MABEL CHILTERN. You’ll stop to luncheon, Lord Caversham, won’t you?

LORD CAVERSHAM. With pleasure, and I’ll drive you down to Downing Street afterwards, Chiltern. You have a great future before you, a great future. Wish I could say the same for you, sir.

[To LORD GORING.]

But your career will have to be entirely domestic.

LORD GORING. Yes, father, I prefer it domestic.

LORD CAVERSHAM. And if you don’t make this young lady an ideal husband, I’ll cut you off with a shilling.

MABEL CHILTERN. An ideal husband! Oh, I don’t think I should like that. It sounds like something in the next world.

LORD CAVERSHAM. What do you want him to be then, dear?

MABEL CHILTERN. He can be what he chooses. All I want is to be . . . to be . . . oh! a real wife to him.

LORD CAVERSHAM. Upon my word, there is a good deal of common sense in that, Lady Chiltern.

[They all go out except SIR ROBERT CHILTERN. He sinks in a chair, wrapt in thought. After a little time LADY CHILTERN returns to look for him.]

LADY CHILTERN.

[Leaning over the back of the chair.]

Aren’t you coming in, Robert?

SIR ROBERT CHILTERN.

[Taking her hand.]

Gertrude, is it love you feel for me, or is it pity merely?

LADY CHILTERN.

[Kisses him.]

It is love, Robert. Love, and only love. For both of us a new life is beginning.

CURTAIN

A Trivial Comedy for Serious People

This play is generally considered to be Wilde’s masterpiece in drama. First performed on 14 February 1895 at St. James’s Theatre in London, it is a farcical comedy in which the protagonists maintain fictitious characters in order to escape burdensome obligations. Working within the social conventions of late Victorian London, the play’s major themes are the triviality with which it treats institutions as serious as marriage, and the resulting satire of Victorian ways.

After the success of

Lady Windermere’s Fan

and

A Woman of No Importance

, Wilde’s producers urged him to write more comedies. In July 1894 he proposed his idea for

The Importance of Being Earnest

to Sir George Alexander, the actor-manager of St. James’s Theatre, who was keen with the premise. Wilde summered with his family at Worthing, where he wrote the play quickly in August. His fame now at its peak, he used the working title

Lady Lancing

to avoid any speculation of its content. Wilde hesitated about submitting the script to Alexander, concerned that it might be unsuitable for the St. James’s Theatre, whose typical repertoire was relatively serious, and explaining that it had been written in response to a request for a play “with no real serious interest”.

When Henry James’ play

Guy Domville

dismally failed, Alexander turned to Wilde and agreed to put on his play. Alexander began his usual meticulous preparations, interrogating the author on each line and planning stage movements with a toy theatre. In the course of these rehearsals Alexander asked Wilde to shorten the play from four acts to three. Wilde agreed and combined elements of the second and third acts. The largest cut was the removal of the character of Mr. Gribsby, a solicitor who comes from London to arrest the profligate “Ernest” (i.e., Jack) for his unpaid dining bills.

Contemporary reviews all praised the play’s humour, though some were cautious about its explicit lack of social messages, while others foresaw the modern consensus that it was the culmination of Wilde’s artistic career so far. Its high farce and witty dialogue have helped make

The Importance of Being Earnest

Wilde’s most enduringly popular play. The successful opening night marked the climax of Wilde’s career, but also heralded his downfall. The Marquess of Queensberry, father of Lord Alfred Douglas, Wilde’s lover, planned to present Wilde a bouquet of spoiling vegetables and disrupt the show. Wilde was tipped off and Queensberry was refused admission. Soon afterwards the feud came to a climax in court and Wilde’s new notoriety caused the play, despite its success, to be closed after just 86 performances. Following his imprisonment, he published the play from Paris, but chose to write no further comic or dramatic work.

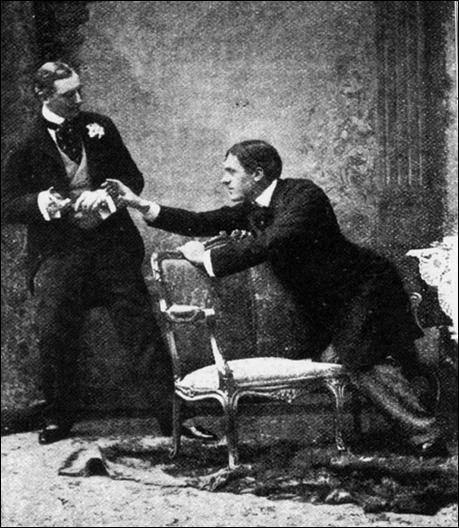

A scene from the 1895 production with Allan Aynesworth as Algernon (left) and Alexander as Jack

Allan Aynesworth, Evelyn Millard, Irene Vanbrugh and George Alexander in the 1895 London premiere

Mrs George Canninge as Miss Prism and Evelyn Millard as Cecily Cardew in the first production

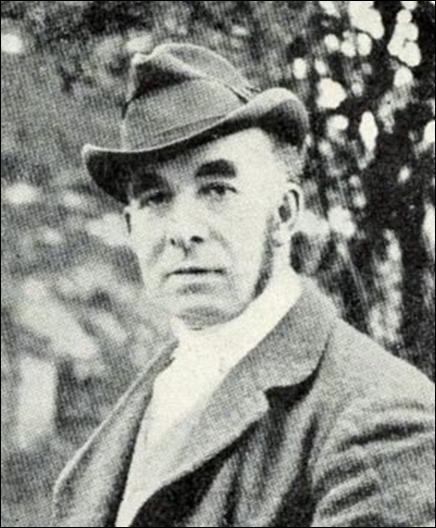

John Sholto Douglas, 9th Marquess of Queensberry (1844–1900) was a Scottish nobleman, remembered for his role in the downfall of Oscar Wilde.

The 1952 film adaptation

The 2002 film adaptation

John Worthing, J.P.

Algernon Moncrieff

Rev. Canon Chasuble, D.D.

Merriman, Butler

Lane, Manservant

Lady Bracknell

Hon. Gwendolen Fairfax

Cecily Cardew

SCENE

Morning-room in Algernon’s flat in Half-Moon Street. The room is luxuriously and artistically furnished. The sound of a piano is heard in the adjoining room.

[

Lane

is arranging afternoon tea on the table, and after the music has ceased,

Algernon

enters.]

Algernon.

Did you hear what I was playing, Lane?

Lane.

I didn’t think it polite to listen, sir.

Algernon.

I’m sorry for that, for your sake. I don’t play accurately — any one can play accurately — but I play with wonderful expression. As far as the piano is concerned, sentiment is my forte. I keep science for Life.

Lane.

Yes, sir.

Algernon.

And, speaking of the science of Life, have you got the cucumber sandwiches cut for Lady Bracknell?

Lane.

Yes, sir.

[Hands them on a salver.]

Algernon.

[Inspects them, takes two, and sits down on the sofa.]

Oh! . . . by the way, Lane, I see from your book that on Thursday night, when Lord Shoreman and Mr. Worthing were dining with me, eight bottles of champagne are entered as having been consumed.

Lane.

Yes, sir; eight bottles and a pint.

Algernon.

Why is it that at a bachelor’s establishment the servants invariably drink the champagne? I ask merely for information.

Lane.

I attribute it to the superior quality of the wine, sir. I have often observed that in married households the champagne is rarely of a first-rate brand.

Algernon.

Good heavens! Is marriage so demoralising as that?

Lane.

I believe it

is

a very pleasant state, sir. I have had very little experience of it myself up to the present. I have only been married once. That was in consequence of a misunderstanding between myself and a young person.

Algernon.

[Languidly

.

]

I don’t know that I am much interested in your family life, Lane.

Lane.

No, sir; it is not a very interesting subject. I never think of it myself.

Algernon.

Very natural, I am sure. That will do, Lane, thank you.

Lane.

Thank you, sir.

[

Lane

goes out.]

Algernon.

Lane’s views on marriage seem somewhat lax. Really, if the lower orders don’t set us a good example, what on earth is the use of them? They seem, as a class, to have absolutely no sense of moral responsibility.

[Enter

Lane

.]

Lane.

Mr. Ernest Worthing.

[Enter

Jack

.]

[

Lane

goes out

.

]

Algernon.

How are you, my dear Ernest? What brings you up to town?

Jack.

Oh, pleasure, pleasure! What else should bring one anywhere? Eating as usual, I see, Algy!

Algernon.

[Stiffly

.

]

I believe it is customary in good society to take some slight refreshment at five o’clock. Where have you been since last Thursday?

Jack.

[Sitting down on the sofa.]

In the country.

Algernon.

What on earth do you do there?

Jack.

[Pulling off his gloves

.

]

When one is in town one amuses oneself. When one is in the country one amuses other people. It is excessively boring.

Algernon.

And who are the people you amuse?

Jack.

[Airily

.

]

Oh, neighbours, neighbours.

Algernon.

Got nice neighbours in your part of Shropshire?

Jack.

Perfectly horrid! Never speak to one of them.

Algernon.

How immensely you must amuse them!

[Goes over and takes sandwich.]

By the way, Shropshire is your county, is it not?

Jack.

Eh? Shropshire? Yes, of course. Hallo! Why all these cups? Why cucumber sandwiches? Why such reckless extravagance in one so young? Who is coming to tea?

Algernon.

Oh! merely Aunt Augusta and Gwendolen.

Jack.

How perfectly delightful!

Algernon.

Yes, that is all very well; but I am afraid Aunt Augusta won’t quite approve of your being here.

Jack.

May I ask why?

Algernon.

My dear fellow, the way you flirt with Gwendolen is perfectly disgraceful. It is almost as bad as the way Gwendolen flirts with you.

Jack.

I am in love with Gwendolen. I have come up to town expressly to propose to her.

Algernon.

I thought you had come up for pleasure? . . . I call that business.

Jack.

How utterly unromantic you are!

Algernon.

I really don’t see anything romantic in proposing. It is very romantic to be in love. But there is nothing romantic about a definite proposal. Why, one may be accepted. One usually is, I believe. Then the excitement is all over. The very essence of romance is uncertainty. If ever I get married, I’ll certainly try to forget the fact.

Jack.

I have no doubt about that, dear Algy. The Divorce Court was specially invented for people whose memories are so curiously constituted.

Algernon.

Oh! there is no use speculating on that subject. Divorces are made in Heaven —

[

Jack

puts out his hand to take a sandwich.

Algernon

at once interferes.]

Please don’t touch the cucumber sandwiches. They are ordered specially for Aunt Augusta.

[Takes one and eats it.]

Jack.

Well, you have been eating them all the time.

Algernon.

That is quite a different matter. She is my aunt.

[Takes plate from below.]

Have some bread and butter. The bread and butter is for Gwendolen. Gwendolen is devoted to bread and butter.

Jack.

[Advancing to table and helping himself.]

And very good bread and butter it is too.

Algernon.

Well, my dear fellow, you need not eat as if you were going to eat it all. You behave as if you were married to her already. You are not married to her already, and I don’t think you ever will be.

Jack.

Why on earth do you say that?

Algernon.

Well, in the first place girls never marry the men they flirt with. Girls don’t think it right.

Jack.

Oh, that is nonsense!

Algernon.

It isn’t. It is a great truth. It accounts for the extraordinary number of bachelors that one sees all over the place. In the second place, I don’t give my consent.

Jack.

Your consent!

Algernon.

My dear fellow, Gwendolen is my first cousin. And before I allow you to marry her, you will have to clear up the whole question of Cecily.

[Rings bell.]

Jack.

Cecily! What on earth do you mean? What do you mean, Algy, by Cecily! I don’t know any one of the name of Cecily.

[Enter

Lane

.]

Algernon.

Bring me that cigarette case Mr. Worthing left in the smoking-room the last time he dined here.

Lane.

Yes, sir.

[

Lane

goes out.]

Jack.

Do you mean to say you have had my cigarette case all this time? I wish to goodness you had let me know. I have been writing frantic letters to Scotland Yard about it. I was very nearly offering a large reward.

Algernon.

Well, I wish you would offer one. I happen to be more than usually hard up.

Jack.

There is no good offering a large reward now that the thing is found.

[Enter

Lane

with the cigarette case on a salver.

Algernon

takes it at once.

Lane

goes out.]

Algernon.

I think that is rather mean of you, Ernest, I must say.

[Opens case and examines it.]

However, it makes no matter, for, now that I look at the inscription inside, I find that the thing isn’t yours after all.

Jack.

Of course it’s mine.

[Moving to him.]

You have seen me with it a hundred times, and you have no right whatsoever to read what is written inside. It is a very ungentlemanly thing to read a private cigarette case.

Algernon.

Oh! it is absurd to have a hard and fast rule about what one should read and what one shouldn’t. More than half of modern culture depends on what one shouldn’t read.

Jack.

I am quite aware of the fact, and I don’t propose to discuss modern culture. It isn’t the sort of thing one should talk of in private. I simply want my cigarette case back.

Algernon.

Yes; but this isn’t your cigarette case. This cigarette case is a present from some one of the name of Cecily, and you said you didn’t know any one of that name.

Jack.

Well, if you want to know, Cecily happens to be my aunt.

Algernon.

Your aunt!

Jack.

Yes. Charming old lady she is, too. Lives at Tunbridge Wells. Just give it back to me, Algy.

Algernon.

[Retreating to back of sofa.]

But why does she call herself little Cecily if she is your aunt and lives at Tunbridge Wells?

[Reading.]

‘From little Cecily with her fondest love.’

Jack.

[Moving to sofa and kneeling upon it.]

My dear fellow, what on earth is there in that? Some aunts are tall, some aunts are not tall. That is a matter that surely an aunt may be allowed to decide for herself. You seem to think that every aunt should be exactly like your aunt! That is absurd! For Heaven’s sake give me back my cigarette case.

[Follows

Algernon

round the room.]

Algernon.

Yes. But why does your aunt call you her uncle? ‘From little Cecily, with her fondest love to her dear Uncle Jack.’ There is no objection, I admit, to an aunt being a small aunt, but why an aunt, no matter what her size may be, should call her own nephew her uncle, I can’t quite make out. Besides, your name isn’t Jack at all; it is Ernest.

Jack.

It isn’t Ernest; it’s Jack.

Algernon.

You have always told me it was Ernest. I have introduced you to every one as Ernest. You answer to the name of Ernest. You look as if your name was Ernest. You are the most earnest-looking person I ever saw in my life. It is perfectly absurd your saying that your name isn’t Ernest. It’s on your cards. Here is one of them.

[Taking it from case.]

‘Mr. Ernest Worthing, B. 4, The Albany.’ I’ll keep this as a proof that your name is Ernest if ever you attempt to deny it to me, or to Gwendolen, or to any one else.

[Puts the card in his pocket.]

Jack.

Well, my name is Ernest in town and Jack in the country, and the cigarette case was given to me in the country.

Algernon.

Yes, but that does not account for the fact that your small Aunt Cecily, who lives at Tunbridge Wells, calls you her dear uncle. Come, old boy, you had much better have the thing out at once.

Jack.

My dear Algy, you talk exactly as if you were a dentist. It is very vulgar to talk like a dentist when one isn’t a dentist. It produces a false impression.