Delphi Complete Works of Sir Arthur Conan Doyle (Illustrated) (1262 page)

Read Delphi Complete Works of Sir Arthur Conan Doyle (Illustrated) Online

Authors: SIR ARTHUR CONAN DOYLE

1st Cheshire. |

1st Dorset. |

Artillery — General Headlam. |

15th Brig. R.F.A. 11, 52, 80. |

27th Brig. R.F.A. 119,120,121. |

28th Brig. R.F.A. 122,123,124. |

8 How. Brig. 37, 61, 65. |

Heavy G.A. 108 Battery. |

R.E. — Colonel Tulloch. |

17th and 59th Field Cos. |

5 Signal Co. |

The Cavalry consisted of four Brigades forming the first cavalry division, and of one extra Brigade. |

They were made up thus: |

1st Cavalry Brigade (Briggs). — 2nd and 5th Dragoon Guards; 11th Hussars. |

2nd Cavalry Brigade (De Lisle). — 4th Dragoon Guards; 9th Lancers; 18th Hussars. |

3rd Cavalry Brigade (Gough). — 4th. Hussars; 5th Lancers; 16th Lancers. |

4th Cavalry Brigade (Bingham). — 3rd Hussars; 6th Dragoon Guards; Comp. Guards Regt. |

5th Cavalry Brigade (Chetwode). — Scots Greys; 12th Lancers; 20th Hussars. |

D, E, I, J, and L batteries of Horse Artillery were attached to these Brigades. |

Such, was the Army which first set forth to measure itself against the soldiers of Germany. Prussian bravery, capacity, and organising power had a high reputation among us, and yet we awaited the result with every confidence, if the odds of numbers were not overwhelming. It was generally known that during the period since the last war the training of the troops had greatly progressed, and many of the men, with nearly all the senior officers, had had experience in the arduous campaign of South Africa. They could also claim those advantages which volunteer troops may hope to have over conscripts. At the same time there was no tendency to underrate the earnest patriotism of our opponents, and we were well aware that even the numerous Socialists who filled their ranks were persuaded, incredible as it may seem, that the Fatherland was really attacked, and were whole-hearted in its defence.

The crossing was safely effected. It has always been the traditional privilege of the British public to grumble at their public servants and to speak of “muddling through” to victory. No doubt the criticism has often been deserved. But on this occasion the supervising General in command, the British War Office, and the Naval Transport Department all rose to a supreme degree of excellence in their arrangements. So too did the Railway Companies concerned. The details were meticulously correct. Without the loss of man, horse, or gun, the soldiers who had seen the sun set in Hampshire saw it rise in Picardy or in Normandy. Boulogne and Havre were the chief ports of disembarkation, but many, including the cavalry, went up the Seine and came ashore at Rouen. The soldiers everywhere received a rapturous welcome from the populace, which they returned by a cheerful sobriety of behaviour. The admirable precepts as to wine and women set forth in Lord Kitchener’s parting orders to the Army seem to have been most scrupulously observed. It is no slight upon the gallantry of France — the very home of gallantry — if it be said that she profited greatly at this strained, over-anxious time by the arrival of these boisterous over-sea Allies. The tradition of British solemnity has been for ever killed by these jovial invaders. It is probable that the beautiful tune, and even the paltry words of “Tipperary,” will pass into history as the marching song, and often the death-dirge, of that gallant host. The dusty, poplar-lined roads resounded with their choruses, and the quiet Picardy villages re-echoed their thunderous and superfluous assurances as to the state of their hearts. All France broke into a smile at the sight of them, and it was at a moment when a smile meant much to France.

Whilst the various brigades were with some deliberation preparing for an advance up-country, there arrived at the Gare du Nord in Paris a single traveller who may be said to have been the most welcome British visitor who ever set foot in the city. He was a short, thick man, tanned by an outdoor life, a solid, impassive personality with a strong, good-humoured face, the forehead of a thinker above it, and the jaw of an obstinate fighter below. Overhung brows shaded a pair of keen grey eyes, while the strong, set mouth was partly concealed by a grizzled moustache. Such was John French, leader of cavalry in Africa and now Field-Marshal commanding the Expeditionary Forces of Britain. His defence of Colesberg at a critical period when he bluffed the superior Boer forces, his dashing relief of Kimberley, and especially the gallant way in which he had thrown his exhausted cavalry across the path of Cronje’s army in order to hold it while Roberts pinned it down at Paardeberg, were all exploits which were fresh in the public mind, and gave the soldiers confidence in their leader.

French might well appreciate the qualities of his immediate subordinates. Both of his army corps and his cavalry division were in good hands. Haig, like his leader, was a cavalry man by education, though now entrusted with the command of the First Army Corps, and destined for an ever-increasing European reputation. Fifty-four years of age, he still preserved all his natural energies, whilst he had behind him long years of varied military experience, including both the Soudanese and the South African campaigns, in both of which he had gained high distinction. He had the advantage of thoroughly understanding the mind of his commander, as he had worked under him as Chief of the Staff in his remarkable operations round Colesberg in those gloomy days which opened the Boer War.

The Second Army Corps sustained a severe loss before ever it reached the field of action, for its commander, General Grierson, died suddenly of heart failure in the train between Havre and Rouen upon August 18. Grierson had been for many years Military Attaché in Berlin, and one can well imagine how often he had longed to measure British soldiers against the self-sufficient critics around him. At the very last moment the ambition of his lifetime was denied him. His place, however, was worthily filled by General Smith-Dorrien, another South African veteran whose brigade in that difficult campaign had been recognised as one of the very best. Smith-Dorrien was a typical Imperial soldier in the world-wide character of his service, for he had followed the flag, and occasionally preceded it, in Zululand, Egypt, the Soudan, Chitral, and the Tirah before the campaign against the Boers. A sportsman as well as a soldier, he had very particularly won the affections of the Aldershot division by his system of trusting to their honour rather than to compulsion in matters of discipline. It was seldom indeed that his confidence was abused.

Haig and Smith-Dorrien were the two generals upon whom the immediate operations were to devolve, for the Third Army Corps was late, through no fault of its own, in coming into line. There remained the Cavalry Division commanded by General Allenby, who was a column leader in that great class for mounted tactics held in South Africa a dozen years before. It is remarkable that of the four leaders in the initial operations of the German War — French, Smith-Dorrien, Haig, and Allenby — three belonged to the cavalry, an arm which has usually been regarded as active and ornamental rather than intellectual. Pulteney, the commander of the Third Army Corps, was a product of the Guards, a veteran of much service and a well-known heavy-game shot. Thus, neither of the more learned corps were represented among the higher commanders upon the actual field of battle, but brooding over the whole operations was the steadfast, untiring brain of Joffre, whilst across the water the silent Kitchener, remorseless as Destiny, moved the forces of the Empire to the front. The last word in each case lay with the sappers.

The general plan of campaign was naturally in the hands of General Joffre, since he was in command of far the greater portion of the Allied Force. It has been admitted in France that the original dispositions might be open to criticism, since a number of the French troops had engaged themselves in Alsace and Lorraine, to the weakening of the line of battle in the north, where the fate of Paris was to be decided. It is small profit to a nation to injure its rival ever so grievously in the toe when it is itself in imminent danger of being stabbed to the heart. A further change in plan had been caused by the intense sympathy felt both by the French and the British for the gallant Belgians, who had done so much and gained so many valuable days for the Allies. It was felt that it would be unchivalrous not to advance and do what was possible to relieve the intolerable pressure which was crushing them. It was resolved, therefore, to abandon the plan which had been formed, by which the Germans should be led as far as possible from their base, and to attack them at once. For this purpose the French Army changed its whole dispositions, which had been formed on the idea of an attack from the east, and advanced over the Belgian frontier, getting into touch with the enemy at Namur and Charleroi, so as to secure the passages of the Sambre. It was in fulfilling its part as the left of the Allied line that on August 18 and 19 the British troops began to move northwards into Belgium. The First Army Corps advanced through Le Nouvion, St. Remy, and Maubeuge to Kouveroy, which is a village upon the Mons-Chimay road. There it linked on to the right of the Second Corps, which had moved up to the line of the Condé-Mons Canal. On the morning of Sunday, August 23, all these troops were in position. The 5th Brigade of Cavalry (Chetwode’s) lay out upon the right front at Binche, but the remainder of the cavalry was brought to a point about five miles behind the centre of the line, so as to be able to reinforce either flank. The first blood of the land campaign had been drawn upon August 22 outside Soignies, when a reconnoitring squadron of the 4th Dragoon Guards under Captain Hornby charged and overthrew a body of the 4th German Cuirassiers, bringing back some prisoners. The 20th Hussars had enjoyed a similar experience. It was a small but happy omen.

The forces which now awaited the German attack numbered about 86,000 men, who may be roughly divided into 76,000 infantry, 10,000 cavalry, and 312 guns. The general alignment was as follows:

The First Army Corps held the space between Mons and Binche, which was soon contracted to Bray as the eastward limit. Close to Mons, where the attack was expected to break, since the town is a point of considerable strategic importance, there was a thickening of the line of defence. From that point the Third Division and the Fifth, in the order named, carried on the British formation down the length of the Mons-Condé Canal. The front of the Army covered nearly twenty miles, an excessive strain upon so small a force in the presence of a compact enemy. If one looks at the general dispositions, it becomes clear that Sir John French was preparing for an attack upon his right flank. From all his information the enemy was to the north and to the east of him, so that if they set about turning his position it must be from the Charleroi direction. Hence, his right wing was laid back at an angle to the rest of his line, and the only cavalry which he kept in advance was thrown out to Binche in front of this flank. The rest of the cavalry was on the day of battle drawn in behind the centre of the Army, but as danger began to develop upon the left flank it was sent across in that direction, so that on the morning of the 24th it was at Thulin, at the westward end of the line.

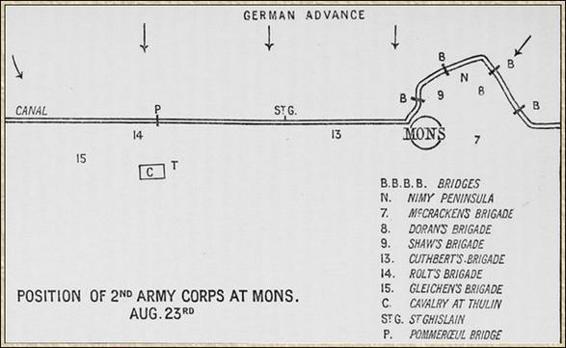

Position of 2nd Army Corps at Mons, August 23, 1914

The line of the canal was a most tempting position to defend from Condé to Mons, for it ran as straight as a Roman road across the path of an invader. But it was very different at Mons itself. Here it formed a most awkward loop. A glance at the diagram will show this formation. It was impossible to leave it undefended, and yet troops who held it were evidently subjected to a flanking artillery Are from each side. The canal here was also crossed by at least three substantial road bridges and one railway bridge. This section of the defence was under the immediate direction of General Smith-Dorrien, who at once took steps to prepare a second line of defence, thrown back to the right rear of the town, so that if the canal were forced the British array would remain unbroken. The immediate care of this weak point in the position was committed to General Beauchamp Doran’s 8th Brigade, consisting of the 2nd Royal Scots, 2nd Royal Irish, 4th Middlesex, and 1st Gordon Highlanders. On their left, occupying the village of Nimy and the western side of the peninsula, as well as the immediate front of Mons itself, was the 9th Brigade (Shaw’s), containing the 4th Royal Fusiliers, the 1st Northumberland Fusiliers, and the 1st Royal Scots Fusiliers, together with the 1st Lincolns. To the left of this brigade, occupying the eastern end of the Mons-Condé line of canal, was Cuthbert’s 13th Brigade, containing the 2nd Scottish Borderers, 2nd West Ridings, 1st West Kents, and 2nd Yorkshire Light Infantry. It was on these three brigades, and especially on the 8th and 9th, that the impact of the German army was destined to fall. Beyond them, scattered somewhat thinly along the line of the Mons-Condé Canal from the railway bridge west of St. Ghislain, were the two remaining brigades of the Fifth Division, the 14th (Rolt’s) and the 15th (Gleichen’s), the latter being in divisional reserve. Still farther to the west the head of the newly arrived 19th Brigade just touched the canal, and was itself in touch with French cavalry at Condé. Sundry units of artillery and field hospitals had not yet come up, but otherwise the two corps were complete.

Having reached their ground, the troops, with no realisation of immediate danger, proceeded to make shallow trenches. Their bands had not been brought to the front, but the universal singing from one end of the line to the other showed that the men were in excellent spirits. Cheering news had come in from the cavalry, detachments of which, as already stated, had ridden out as far as Soignies, meeting advance patrols of the enemy and coming back with prisoners and trophies. The guns were drawn up in concealed positions within half a mile of the line of battle. All was now ready, and officers could be seen on every elevation peering northwards through their glasses for the first sign of the enemy. It was a broken country, with large patches of woodland and green spaces between. There were numerous slag-heaps from old mines, with here and there a factory and here and there a private dwelling, but the sappers had endeavoured in the short time to clear a field of fire for the infantry. In order to get this field of fire in so closely built a neighbourhood, several of the regiments, such as the West Kents of the 13th and the Cornwalls of the 14th Brigades, had to take their positions across the canal with bridges in their rear. Thrilling with anticipation, the men waited for their own first entrance upon the stupendous drama. They were already weary and footsore, for they had all done at least two days of forced marching, and the burden of the pack, the rifle, and the hundred and fifty rounds per man was no light one. They lay snugly in their trenches under the warm August sun and waited. It was a Sunday, and more than one have recorded in their letters how in that hour of tension their thoughts turned to the old home church and the mellow call of the village bells.