Delphi Complete Works of Sir Arthur Conan Doyle (Illustrated) (1288 page)

Read Delphi Complete Works of Sir Arthur Conan Doyle (Illustrated) Online

Authors: SIR ARTHUR CONAN DOYLE

About ten o’clock on the morning of the 20th the German attack, driving back the Sirhind Brigade from Givenchy, who were the left advanced flank of the Lahore Division, came with a rush against the Dehra-Dun Brigade, who were the extreme right of the Meerut Division. This Brigade had the 1st Seaforth Highlanders upon its flank, with the 2nd Ghurkas upon its left. The Ghurkas were forced to retire, and the almost simultaneous retirement of the defenders of Givenchy left the Highlanders in a desperate position with both flanks in the air. Fortunately the next Brigade of the Meerut Division, the Garhwal Brigade, stood fast and kept in touch with the 6th Jats, who formed the left of the Dehra Dun Brigade, and so prevented the pressure upon that side from becoming intolerable. The 9th Ghurkas came up to support the 2nd Ghurkas, who had not gone far from their abandoned trenches, and the 58th Indian Rifles also came to the front. These battalions upon the left rear of the Highlanders gave them some support. None the less the position of the battalion was dangerous and its losses heavy, but it faced the Germans with splendid firmness, and nothing could budge it. Machine-guns are stronger than flesh and blood, but the human spirit can be stronger than either. You might kill the Highlanders, but you could not shift them. The 2nd Black Watch, who had been in reserve, established touch towards nightfall with the right of the Seaforths, and also with the left of the Sirhind Brigade, so that a continuous line was assured.

In the meantime a small force had assembled under General MacBean with the intention of making a counter-attack and recovering the ground which had been lost on the north side of Givenchy, With the 8th Ghurkas and the 47th Sikhs, together with the 7th British Dragoon Guards, an attack was made in the early hours of the 21st. Colonel Lempriere of the Dragoon Guards was killed, and the attack failed. It was renewed in the early hours of the morning, but it again failed to dislodge the Germans from the captured trenches.

December 21 dawned upon a situation which was not particularly rosy from a British point of view. It is true that Givenchy had been recovered, but a considerable stretch of trenches were still in the hands of the Germans, their artillery was exceedingly masterful, and the British line was weakened by heavy losses and indented in several places. The one bright spot was the advance of the First Division of Haig’s Corps, who had come up in the night-time. The three brigades of this Division were at once thrown into the fight, the first being sent to Givenchy, the second given as a support to the Meerut Division, and the third directed upon the trenches which had been evacuated the day before by the Sirhind Brigade. All of these brigades won their way forward, and by the morning of the 22nd much of the ground which had been taken by the Germans was reoccupied by the British. The 1st Brigade, led by the Cameron Highlanders, had made good all the ground between Givenchy and the canal. Meanwhile the 3rd Brigade had re-established the Festubert position, where the 2nd Welsh and 1st South Wales Borderers had won their way into the lost trenches of the Ghurkas. This was not done without very stark fighting, in which of all the regiments engaged none suffered so heavily as the 2nd Munsters (now attached to the 3rd Brigade). This regiment, only just built up again after its practical extermination at Étreux in August, made a grand advance and fought without cessation for nearly forty-eight hours. Their losses were dreadful, including their gallant Colonel Bent, both Majors Day and Thomson, five other officers, and several hundreds of the rank and file. So far forward did they get that it was with great difficulty that the survivors, through the exertions of Major Ryan, were got back into a place of safety. It was the second of three occasions upon which this gallant Celtic battalion gave itself for King and Country. Let this soften the asperity of politics if unhappily we must come back to them after the war.

Meanwhile the lines upon the flank of the Seaforths which had been lost by the Dehra-Dun Brigade were carried by the 2nd Brigade (Westmacott), the 1st North Lancashire and 1st Northamptons leading the attack with the 2nd Rifles in support. Though driven back by a violent counter-attack in which both leading regiments, and especially the Lancashire men, lost heavily, the Brigade came again, and ended by making good the gap in the line. Thus the situation on the morning of the 22nd looked very much better than upon the day before. On this morning, as so many of the 1st Corps were in the advanced line, Sir Douglas Haig took over the command from Sir James Willcocks. The line had been to some extent re-established and the firing died away, but there were some trenches which were not retaken till a later date.

Such was the scrambling and unsatisfactory fight of Givenchy, a violent interlude in the drab records of trench warfare. It began with a considerable inroad of Germans into our territory and heavy losses of our Indian Contingent. It ended by a general return of the Germans to their former lines, and the resumption by the veteran troops of the First Division of the main positions which we had lost. Neither side had gained any ground of material value, but the balance of profit in captures was upon the side of the Germans, who may fairly claim that the action was a minor success for their arms, since they assert that they captured some hundreds of prisoners and several machine-guns. The Anglo-Indian Corps had 2600 casualties, and the First Corps 1400, or

About the same date as the Battle of Givenchy there was some fighting farther north at Rouge Banc, where the Fourth Corps was engaged and some German trenches were taken. The chief losses in this affair fell upon those war-worn units, the 2nd Scots Guards and 2nd Borderers of the 20th Brigade. Henceforward peace reigned along the lines for several weeks — indeed Christmas brought about something like fraternisation between British and Germans, who found a sudden and extraordinary link in that ancient tree worship, long anterior to Christianity, which Saxon tribes had practised in the depths of Germanic forests and still commemorated by their candle-lit firs. For a single day the opposing forces mingled in friendly conversation and even in games. It was an amazing spectacle, and must arouse bitter thoughts concerning those high-born conspirators against the peace of the world, who in their mad ambition had hounded such men on to take each other by the throat rather than by the hand. For a day there was comradeship. But the case had been referred to the God of Battles, and the doom had not yet been spoken. It must go to the end. On the morning of the 26th dark figures vanished reluctantly into the earth, and the rifles cracked once more. It remains one human episode amid all the atrocities which have stained the memory of the war.

So ended 1914, the year of resistance. During it the Western Allies had been grievously oppressed by their well-prepared enemy. They had been overweighted by numbers and even more so by munitions. For a space it had seemed as if the odds were too much for them. Then with a splendid rally they had pushed the enemy back. But his reserves had come up and had proved to be as superior as his first line had been. But even so he had reached his limit. He could get no further. The danger hour was past. There was now coming the long, anxious year of equilibrium, the narrative of which will be given in the succeeding volume of 1915. Finally will come the year of restoration which will at least begin, though it will not finish, the victory of the champions of freedom.

THE END

IN the previous volume of this work, which dealt with the doings of the British Army in France and Flanders during the year 1914, I ventured to claim that a great deal of it was not only accurate but that it was very precisely correct in its detail. This claim has been made good, for although many military critics and many distinguished soldiers have read it there has been no instance up to date of any serious correction. Emboldened by this I am now putting forward an account of the doings of 1915, which will be equally detailed and, as I hope, equally accurate. In the late autumn a third volume will carry the story up to the end of 1916, covering the series of battles upon the Somme.

The three years of war may be roughly divided into the year of defence, the year of equilibrium, and the year of attack. This volume concerns itself with the second, which in its very nature must be less dramatic than the first or third. None the less it contains some of the most moving scenes of the great world tragedy, and especially the second Battle of Ypres and the great Battle of Loos, two desperate conflicts the details of which have not, so far as I know, been given up to now to the public.

Now, as before, I must plead guilty to many faults of omission, which often involve some injustice, since an author is naturally tempted to enlarge upon what he knows at the expense of that about which he is less well informed. These faults may be remedied with time, but in the meantime I can only claim indulgence for the obvious difficulty of my task. With the fullest possible information at his disposal, I do not envy the task of the chronicler who has to strike a just balance amid the claims of some fifty divisions.

Arthur Conan Doyle, Windlesham, Crowborough, April 1917.

Conflict of the 1st Brigade at Cuinchy, and of the 3rd Brigade at Givenchy — Heavy losses of the Guards — Michael O’Leary, V.C. — Relief of French Divisions by the Twenty-seventh and Twenty-eighth — British Pressure on the Fifth Corps — Force subdivided into two armies — Disaster to 16th Lancers — The dearth of munitions

THE weather after the new year was atrocious, heavy CHAPTER rain, frost, and gales of wind succeeding each other L with hardly a break. The ground was so sodden that The . all movements of troops became impossible, and the months trench work was more difficult than ever. The British, with their steadily increasing numbers, were now able to take over some of the trenches of the French and to extend their general line. This trench work came particularly hard upon the men who were new to the work and often fresh from the tropics. A great number of the soldiers contracted frost-bite and other ailments. The trenches were very wet, and the discomfort was extreme. There had been some thousands of casualties in the Fifth Corps from this cause before it can be said to have been in action. On the other hand, the medical service, which was extraordinarily efficient, did everything possible to preserve the health of the men. Wooden troughs were provided as a stance for them in the trenches, and vats heated to warm them when they emerged. Considering that typhoid fever was common among the civilian residents the health of the troops remained remarkably good, thanks to the general adoption of inoculation, a practice denounced by a handful of fanatics at home, but of supreme importance at the front, where the lesson of old wars, that disease was more deadly than the bullet, ceased to hold good.

On January 25 the Germans again became aggressive. If their spy system is as good as is claimed, they must by this time have known that all talk of bluff in connection with the new British armies was mere self-deception, and that if ever they were to attempt anything with a hope of success, it must be speedily before the line had thickened. As usual there was a heavy bombardment, and then a determined infantry advance this time to the immediate south of the Bethune Canal, where there was a salient held by the 1st Infantry Brigade with the French upon their right. The line was thinly held at the time by a half- battalion 1st Scots Guards and a half-battalion 1st Coldstream, a thousand men in all. One trench of the Scots Guards was blown up by a mine and the German infantry rushed it, killing, wounding, or taking every man of the 130 defenders. Three officers were hit, and Major Morrison-Bell, a member of parliament, was taken after being buried in the debris of the explosion. The remainder of the front line, after severe losses both in casualties and in prisoners, fell back from the salient and established themselves with the rest of their respective battalions on a straight line of defence, one flank on the canal, the other on the main Bethune-La Bassée high road. A small redoubt or keep had been established here, which became the centre of the defence.

Whilst the advance of the enemy was arrested at this line, preparations were made for a strong counter-attack. An attempt had been made by the enemy with their heavy guns to knock down the lock gates of the canal and to flood the ground in the rear of the position. This, however, was unsuccessful, and the counter-attack dashed to the front. The advancing troops consisted of the 1st Black Watch, part of the 1st Camerons, and the 2nd Rifles from the reserve. The London Scottish supported the movement. The enemy had flooded past the keep, which remained as a British island in a German lake. They were driven back with difficulty, the Black Watch advancing through mud up to their knees and losing very heavily from a cross fire. Two companies were practically destroyed. Finally, by an advance of the Rifles and 2nd Sussex after dark the Germans were ousted from all positions in advance of the keep, and this line between the canal and the road was held once more by the British. The night fell, and after dark the 1st Brigade, having suffered severely, was withdrawn, and the 2nd Brigade remained in occupation with the French upon their right. This was the action of Cuinchy falling upon the 1st Brigade, supported by part of the 2nd.

Whilst this long-drawn fight of January 25 had been going on to the south of the canal, there had been a vigorous German advance to the north of it, over the old ground which centres on Givenchy. The German attack, which came on in six lines, fell principally upon the 1st Gloucesters, who held the front trench. Captain Richmond, who commanded the advanced posts, had observed at dawn that the German wire had been disturbed and was on the alert. Large numbers advanced, but were brought to a standstill about forty yards from the position. These were nearly all shot down. Some of the stormers broke through upon the left of the Gloucesters, and for a time the battalion had the enemy upon their flank and even in their rear, but they showed great steadiness and fine fire discipline. A charge was made presently upon the flank by the 2nd Welsh aided by a handful of the Black Watch under Lieutenant Green, who were there as a working party, but found more congenial work awaiting them. Lieutenant Bush of the Gloucesters with his machine-guns did particularly fine work. This attack was organised by Captain Kees, aided by Major MacNaughton, who was in the village as an artillery observer. The upshot was that the Germans on the flank were all killed, wounded, or taken. A remarkable individual exploit was performed by Lieutenant James and Corporal Thomas of the Welsh, who took a trench with 40 prisoners. A series of attacks to the north- east of the village were also repulsed, the South Wales Borderers doing some splendid work.

Thus the results of the day’s fighting was that on the north the British gained a minor success, beating off all attacks, while to the south the Germans could claim an advantage, having gained some ground. The losses on both sides were considerable, those of the British being principally among Scots Guards, Coldstream and Black Watch to the south, and Welsh to the north. The action was barren of practical results.

There were some days of quiet, and then upon January 29 the Fourteenth German Corps buzzed out once more along the classic canal. This time they made for the keep, which has already been mentioned, and endeavoured to storm it with the aid of axes and scaling ladders. Solid Sussex was inside the keep, however, and ladders and stormers were hurled to the ground, while bombs were thrown on to the heads of the attackers. The Northamptons to the south were driven out for an instant, but came back with a rush and drove off their assailants. The skirmish cost the British few casualties, but the enemy lost heavily, leaving two hundred of his dead behind him. “Having arranged a code signal we got the first shell from the 40th R.F.A. twelve seconds after asking for it.” So much for the co-operation between our guns and our infantry.

On February 1 the Guards who had suffered in the first fight at Cuinchy got back a little of what was owing to them. The action began by a small post of the 2nd Coldstream of the 4th Brigade being driven back. An endeavour was made to reinstate it in the early morning, but it was not successful. After daylight there was a proper artillery preparation, followed by an assault by a storming party of Coldstream and Irish Guards, led by Captain Leigh Bennett and Lieutenant Graham. The lost ground and a German trench beyond it were captured with 32 prisoners and 2 machine-guns. It was in this action that Michael O’Leary, the gallant Irish Guardsman, shot or bayoneted eight Germans and cleared a trench single-handed, one of the most remarkable individual feats of the War, for which a Victoria Cross was awarded. Again the fight fell upon the 4th Brigade, where Lord Cavan was gaining something of the reputation of his brother peer, Lord “Salamander” Cutts, in the days of Marlborough. On February 6 he again made a dashing attack with a party of the 3rd Coldstream and Irish, in which the Germans were driven out of the Brickfield position. The sappers under Major Fowkes rapidly made good the ground that the infantry had won, and it remained permanently with the British.

Another long lull followed this outburst of activity in the region of the La Bassée Canal, and the troops sank back once more into their muddy ditches, where, under the constant menace of the sniper, the bomb and the shell, they passed the weary weeks with a patience which was as remarkable as their valour. The British Army was still gradually relieving the French troops, who had previously relieved them. Thus in the north the newly-arrived Twenty-seventh and Twenty-eighth Divisions occupied several miles which had been held on the Ypres salient by General D’Urbal’s men. Unfortunately, these two divisions, largely composed of men who had come straight from the tropics, ran into a peculiarly trying season of frost and rain, which for a time inflicted great hardship and loss upon them. To add to their trials, the trenches at the time they took them over were not only in a very bad state of repair, but had actually been mined by the Germans, and these mines were exploded shortly after the transfer, to the loss of the new occupants. The pressure of the enemy was incessant and severe in this part of the line, so that the losses of the Fifth Corps were for some weeks considerably greater than those of all the rest of the line put together. Two of the veteran brigades of the Second Corps, the 9th Fusilier Brigade (Douglas Smith) and the 13th (Wanless O’Gowan), were sent north to support their comrades, with the result that this sector was once again firmly held. Any temporary failure was in no way due to a weakness of the Fifth Army Corps, who were months to prove their mettle in many a future fight, but came from the fact, no doubt unavoidable but none the less unfortunate, that these troops, before they had gained any experience, were placed in the very worst trenches of the whole British line. “The trenches (so called) scarcely existed,” said one who went through this trying experience, “and the ruts which were honoured with the name were liquid. We crouched in this morass of water and mud, living, dying, wounded and dead together for 48 hours at a stretch.” Add to this that the weather was bitterly cold with incessant rain, and more miserable conditions could hardly be imagined. In places the trenches of the enemy were not more than twenty yards off, and the shower of bombs was incessant.

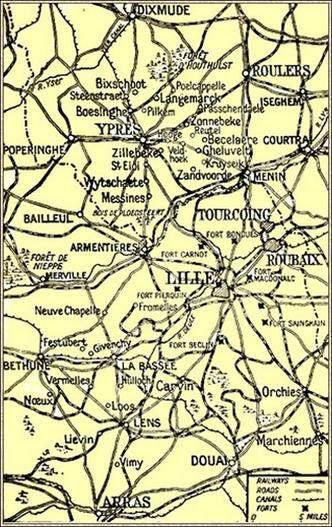

The British Army had now attained a size when it was no longer proper that a corps should be its highest unit. From this time onwards the corps were themselves distributed into different armies. At present, two of these armies were organised. The First, under General Sir Douglas Haig, comprised the First Corps, the Fourth Corps (Rawlinson), and the Indian Corps. The Second Army contained the Second Corps (Ferguson), the Third Corps (Pulteney), and the Fifth Corps (Plumer), all under Sir Horace Smith-Dorrien. The new formations as they came out were either fitted into these or formed part of a third army. Most of the brigades were strengthened by the addition of one, and often of two territorial battalions. Each army consisted roughly at this time of 120,000 men. The Second Army was in charge of the line to the north, and the First to the south.

On February 14 Snow’s Twenty-seventh Division, which had been somewhat hustled by the Germans in the Ypres section, made a strong counter-attack under the cover of darkness, and won back four trenches near St. Eloi from which they had been driven by a German rush. This dashing advance was carried out by the 82nd Brigade (Longley’s), and the particular battalions which were most closely engaged were the 2nd Cornwalls, the 1st Royal Irish, and 2nd Royal Irish Fusiliers. They were supported by the 80th Brigade (Fortescue’s). The losses amounted to 300 killed and wounded. The Germans lost as many and a few prisoners were taken. The affair was of no great consequence in itself, but it marked a turn in the affairs of Plumer’s Army Corps, whose experience up to now had been depressing. The enemy, however, was still aggressive and enterprising in this part of the line. Upon the 20th they ran a mine under a trench occupied by the 16th Lancers, and the explosion produced most serious effects. 5 officers killed, 3 wounded, and 60 men

hors de combat

were the fruits of this unfortunate incident, which pushed our trenches back for

On the 21st, the Twenty-eighth Division near Ypres had a good deal of hard fighting, losing trenches and winning them, but coming out at the finish rather the loser on balance. The losses of the day were 250 killed and wounded, the greatest sufferers being months the Royal Lancasters. Somewhat south of Ypres, at Zwarteleen, the 1st West Kents were exposed to a shower of projectiles from the deadly

Minenwerfer

, which are more of the nature of aerial torpedoes than ordinary bombs. Their losses under this trying ordeal were 3 officers and 19 men killed, 1 officer and 18 men wounded. There was a lull after this in the trench fighting for some little time, which was broken upon February 28 by a very dashing little attack of the Princess Patricia’s Canadian regiment, which as one of the units of the 80th Brigade had been the first Canadian Battalion to reach the front. Upon this occasion, led by Lieutenants Crabb and Papineau, they rushed a trench in their front, killed eleven of its occupants, drove off the remainder, and levelled it so that it should be untenable. Their losses in this exploit were very small. During this period of the trench warfare it may be said generally that the tendency was for the Germans to encroach upon British ground in the Ypres section and for the British to take theirs in the region of La Bassée.