Delphi Complete Works of Sir Arthur Conan Doyle (Illustrated) (1339 page)

Read Delphi Complete Works of Sir Arthur Conan Doyle (Illustrated) Online

Authors: SIR ARTHUR CONAN DOYLE

Italian armies had in the meanwhile given a splendid account of themselves, as every one who had seen them in the field, predicted that they would. Though hard pressed by a severe Austrian attack in the Trentino in May, they rallied and held the enemy before he could debouch upon the plains. Then with three hard blows delivered upon August 6 to August 9, where they took the town of Gorizia and 12,000 prisoners, on October 10, and on November 1 they broke the Austrian lines and inflicted heavy losses upon them. The coming of winter saw them well upon their way to Trieste.

On August 4 the British forces in Egypt defeated a fresh Turco-German attack upon that country. The battle was near Romani, east of the Suez Canal, and it ended in a creditable victory and the capture of 2500 prisoners. This was the end of the serious menace for Egypt, and the operations in this quarter, which were carried on by General Murray, were confined from this time forwards to clearing up the Sinai peninsula, where various Turkish posts were dispersed or taken, and in advancing our line to the Palestine Frontier.

On August 8 our brave little ally, Portugal, threw her sword into the scale of freedom, and so gave military continuity to the traditions of the two nations. It would have rejoiced the austere soul of the great Duke to see the descendants of his much-valued Caçadores, fighting once more beside the great-grandsons of the Riflemen and Guardsmen of the Peninsula. Two divisions appeared in France, where they soon made a reputation for steadiness and valour.

In the East another valiant little nation had also ranged herself with the Allies, and was destined, alas, to meet her ruin through circumstances which were largely beyond her own control. Upon August 27 Romania declared war, and with a full reliance upon help which never reached her, advanced at once into the south of Hungary. Her initial successes changed to defeat, and her brave soldiers, who were poorly provided with modern appliances of war, were driven back before the pressure of Falkenhayn’s army in the west and Mackensen’s, which eventually crossed the Danube, from the south. On December 6 Bucharest fell, and by the end of the year the Romanians had been driven to the Russian border, where, an army without a country, they hung on, exactly as the Belgians had done, to the extreme edge of their ravaged fatherland. To their Western allies, who were powerless to help them, it was one of the most painful incidents of the War.

The Salonica expedition had been much hampered by the sinister attitude of the Greeks, whose position upon the left rear of Sarrail’s forces made an advance dangerous, and a retreat destructive. King Constantine, following the example of his brother-in-law of Berlin, had freed himself from all constitutional ties, refused to summon a parliament, and followed his own private predilections and interests by helping our enemies, even to the point of surrendering a considerable portion of his own kingdom, including a whole army corps and the port of Kavala, to the hereditary enemy, the Bulgarian. Never in history has a nation been so betrayed by its king, and never, it may be added, did a nation which had been free allow itself so tamely to be robbed of its freedom.

Venezelos, however, showed himself to be a great patriot, shook the dust of Athens from his feet, and departed to Salonica, where he raised the flag of a fighting national party, to which the whole nation was eventually rallied. Meanwhile, however, the task of General Sarrail was rendered more difficult, in spite of which he succeeded in regaining Monastir and establishing himself firmly within the old Serbian frontier — a result which was largely due to the splendid military qualities of the remains of the Serbian army.

On December 12 the German Empire proposed negotiations for peace, but as these were apparently to be founded upon the war-map as it then stood, and as they were accompanied by congratulatory messages about victory from the Kaiser to his troops, they were naturally not regarded as serious by the Allies. Our only guarantee that a nation will not make war whenever it likes is its knowledge that it cannot make peace when it likes, and this was the lesson which Germany was now to learn. By the unanimous decision of all the Allied nations no peace was possible which did not include terms which the Germans were still very far from considering — restitution of invaded countries, reparation for harm done, and adequate guarantees against similar unprovoked aggression in the future. Without these three conditions the War would indeed have been fought in vain.

This same month of December saw two of the great protagonists who had commenced the War retire from that stage upon which each had played a worthy part. The one was Mr. Asquith, who, weary from long labours, gave place to the fresh energy of Mr. Lloyd George. The other was “Father” Joffre, who bore upon his thick shoulders the whole weight of the early campaigns. Both of the names will live honourably in history.

And now as the year drew to its close, Germany, wounded and weary, saw as she glared round her at her enemies, a portent which must have struck a chill to her heart. Russian strength had been discounted and that of France was no new thing. But whence came this apparition upon her Western flank — a host raised, as it seemed, from nowhere, and yet already bidding fair to be equal to her own? Her public were still ignorant and blind, bemused by the journals which had told them so long, and with such humorous detail, that the British army was a paper army, the creature of a dream. Treitschke’s foolish phrase, “The unwarlike Islanders,” still lingered pleasantly in their memory. But the rulers, the men who knew, what must have been their feelings as they gazed upon that stupendous array, that vision of doom, a hundred miles from wing to wing, gleaming with two million bayonets, canopied with aeroplanes, fringed with iron-clad motor monsters, and backed by an artillery which numbered its guns by the thousand? Kitchener lay deep in the Orkney waves, but truly his spirit was thundering at their gates. His brain it was who first planted these seeds, but how could they have grown had the tolerant, long-suffering British nation not been made ready for it by all those long years of Teutonic insult, the ravings of crazy professors, and the insults of unbalanced publicists? All of these had a part in raising that great host, but others, too, can claim their share: the baby-killers of Scarborough, the Zeppelin murderers, the submarine pirates, all the agents of ruthlessness. Among them they had put life and spirit into this avenging apparition, where even now it could be said that every man in the battle line had come there of his own free will. Years of folly and of crime were crying for a just retribution. The instrument was here and the hour was drawing on.

This, the fourth volume of The British Campaign in France and Flanders, carries the story through the long and arduous fighting of 1917, which culminated in the dramatic twofold battle of Cambrai. These events are cut deep into the permanent history of the world, and we are still too near it to read the whole of that massive and tremendous inscription. It is certain, however, that this year marked the period in which the Allies gained a definite military ascendancy over the German forces, in spite of the one great subsequent rally which had its source in events which were beyond the control of the Western powers. So long as ink darkens and paper holds, our descendants, whose freedom has been won by these exertions, will dwell earnestly and with reverence upon the stories of Arras, Messines, Ypres, Cambrai, and other phases of this epic period.

I may be permitted to record with some thankfulness and relief, that in the course of three thick volumes, in which for the first time the detailed battle-line of these great encounters has been set out, it has not yet been shown that a brigade has ever been out of its place, and even a battalion has seldom gone amiss. Such good fortune cannot last for ever.

Absit omen!

But the fact is worth recording, as it may reassure the reader who has natural doubts whether history which is so recent can also lay claim to be of any permanent value.

The Censorship has left me untrammelled in the matter of units, for which I am sufficiently grateful. The ruling, however, upon the question of names must be explained, lest it should seem that their appearance or suppression is due to lack of knowledge or to individual favour or caprice. I would explain, then, that I am permitted to use the names of Army and Corps Commanders, but only of such divisional Generals as are mentioned in the Headquarters narrative. All other ranks below divisional Generals are still suppressed, save only casualties, in connection with the action where they received the injury, and those who won honours, with the same limitation. This regulation has little effect upon the accuracy of the narrative, but it appears in many cases to involve some personal injustice. To record the heroic deeds of a division and yet be compelled to leave out the name of the man who made it so efficient, is painful to the feelings of the writer, for if any one fact is clearer than another in this war it is that the good leader makes the good unit.

The tremendous epic of 1918 will call for two volumes in its treatment. One of these, bringing the story up to June 30, 1918, is already completed, and should appear by the summer. The other may be ready at the end of the year.

ARTHUR CONAN DOYLE,

Crowborough,

January 20, 1919.

I. THE GERMAN RETREAT

UPON THE ARRAS-SOISSONS FRONT

Hindenburg’s retreat — The advance of the Fifth and Fourth Armies — Capture of Bapaume and Peronne — Atrocious devastation by the Germans — Capture of guns at Selency — Definition of the Hindenburg Line — General survey

IN the latter days of 1916 and the beginning of 1917, the British Army, which had in little more than two years expanded from seven divisions to over fifty, took over an increased line. The movement began about Christmas time, and early in the New Year Rawlinson’s Fourth Army, side-stepping always to the south, had covered the whole of the French position occupied during the Somme fighting, had crossed the Somme, and had established its right flank at a point near Roye. The total front was increased to

The general disposition of the British forces after prolongation to the south was as follows. Plumer’s Second Army still held that post of danger and of honour which centred round the Ypres salient. South of Plumer, in the Armentières district, was the First Army, now commanded by General Horne, whose long service with the Fifteenth Corps during the Somme Battle had earned him this high promotion. Allenby’s Third Army carried the line onwards to the south of Arras. From the point upon which the British line had hinged during the Somme operations Gough’s Fifth Army took over the front, and this joined on to Rawlinson’s Fourth Army near the old French position. From the north then the order of the armies was two, one, three, five, and four.

The winter was spent by both sides in licking their wounds after the recent severe fighting and in preparing for the greater fighting to come. These preparations upon the part of the British consisted in the addition to the army of a number of fresh divisions, and the rebuilding of those divisions, fifty-two in number, which had taken part in the Somme fighting, most of them more than once. As the average loss in these divisions was very heavy indeed, the task of reconstructing them was no light one. None the less before the campaign re-opened, though the interval was a short three months, the greater part of the battalions were once again at full strength, while the guns and munitions were very greatly increased. A considerable addition to the strength of the army was effected by the civilian railway advisers, under Sir Eric Geddes, who by the simple expedient and re-laying them in France, enormously improved the communications of the army.

In the case of the Germans their army changes took the form of a considerable new levy from those classes which had been previously judged to be unfit, and a general comb-out of every source from which men could be extracted. A new law rendered every citizen liable to national service in a civilian capacity, and so released a number of men from the mines and the factories. They also increased the numbers of their divisions by the doubtful expedient of reducing the brigades, so that the divisions were shorn of a third of their strength. The battalions thus obtained were formed into new divisions. In this way it was calculated that a reserve force had been created which would be suddenly thrown in on one or the other front with dramatic effect. Some such plan may have been in contemplation, but as a matter of fact the course of events was such that the German generals required every man and more for their own immediate needs during the whole of the year.

It has been shown in the narrative of 1916 how the British had ended the campaign of that year by the brilliant little victory of Beaumont Hamel, which gave them not merely 7000 prisoners, but command of both sides of the Valley of the Ancre. This victory had been the sequel to the capture of the Thiepval Ridge, and this again had depended upon the general success of the Somme operations, so that the turn of events which led to such considerable results always traces back to the tragic and glorious 1st of July.

It was clear that whenever the weather permitted the resumption of hostilities, Sir Douglas Haig was in so commanding a position at this point that he was perfectly certain to drive the enemy out of the salient which they held to the north of Beaumont Hamel. The result showed that this expectation was well founded, but no one could have foreseen how considerable was the retreat which would be forced upon the enemy — a retreat which gave away for nothing the ground which cost Hindenburg so much to regain in the following year.

Although the whole line from the sea to the Somme was a scene of activity during the winter, and though hardly a day, or rather a night, went by that some stealthy party did not cross No-Man’s-Land to capture and to destroy, still for the purposes of this narrative the three northern armies may be entirely ignored in the succeeding operations since they had no occasion to alter their lines. We shall fix our attention in the first instance upon Gough’s Army in the district of the Ancre, and afterwards upon Rawlinson’s which was drawn into the operations. Gough’s Army consisted, at the beginning of the year, of three corps, the Fifth (E.A. Fanshawe) to the left covering the ground to the north of the Ancre, the Second Corps (Jacob) immediately south of the river, and the First Australian Corps (Birdwood) extending to the junction with Rawlinson’s Army, and covering the greater part of the old British line upon the Somme. It was upon the Fifth and the Second Corps that the immediate operations which opened the campaign were to devolve.

The Fifth Corps was formed at this period of three divisions, the Eleventh, Thirty-first, and Seventh. Each of these divisions by constant pressure and minor operations, backed by a powerful artillery fire, played a part in the wearing process of constant attrition which ended in making the position of the Germans impossible. On January 10, the 32nd Yorkshire Brigade of the Eleventh Division carried an important trench due east of Beaumont Hamel, taking 140 prisoners. On the next day the movement extended farther north, where three-quarters of a mile of trench with 200 prisoners was the prize. On January 17, another

The chief initiative still rested with the latter, and upon February 3 another push forward of

Upon February 10 the left of the Fifth Corps began to feel out towards Serre, that village of sinister memories, and 215 prisoners were taken from the trenches to the south of the hamlet. This provoked a new counter from the enemy which was beaten back upon February

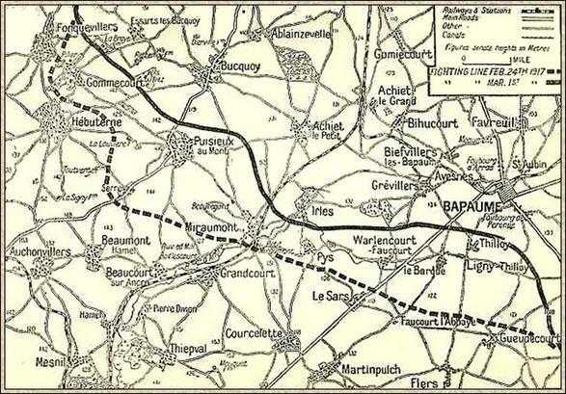

All these advances, with their accompanying and ever-extending bombardments, had been like those multiplied causes, each small in itself, which eventually loosen and start a great landslide. The effect must undoubtedly have been begun some weeks before when the Germans perceived that they could no longer hold on, and favoured by wind, rain, and fog, started their rearward movement to the great permanent second line, the exact position of which was still vague to the Allies. Upon February 25 the whole German front caved in for a depth of three miles both north and south of the Ancre. Wading through seas of mud Gough’s infantry occupied Serre, Pys, Miraumont, Eaucourt, Warlencourt, and all the ground for eleven miles from Gomiecourt in the north to Gueudecourt in the south. On February 28 Gomiecourt itself had been occupied by the North Country troops of the Thirty-first Division, while Puisieux and Thilloy had also been added to the British line. The advance was not unopposed. The battle-patrols continually extended to attack some trench of snipers or nest of machine-guns. Mined roads and all manner of obstructions impeded the onward flow of the army. The retreat was orderly and skilful, and the pursuit was necessarily slow and wary. By a pleasing coincidence the Thirty-first Division, which occupied Serre, was the same brave North Country Division which had lost so heavily upon July 1 and November 13 on the same front. On entering the village they actually found the bodies of some of their own brave comrades who had got as far forward seven months before.

On March 4 the advance which had steadily continued in the north spread suddenly southwards to Bouchavesnes north of Peronne, the sector held by the Twentieth and Forty-eighth Divisions of Rawlinson’s Army, which from this time onward was more and more engaged in the forward movement. Three machine-guns and 172 prisoners were taken.

There was some interruption of the operations at this stage owing to severe snowstorms, but upon March 10 Irles, west of Bapaume, was taken by assault by the Eighteenth Division. This was a formidable point, well wired and trenched, so that the artillery in full force was needed for preparation. The infantry went forward before sunrise, and within an hour the village with 15 machine-guns and 290 prisoners was in British hands. The losses were light and the gain substantial. Grevillers also fell next day. This advance in front of Bapaume was of importance as it turned Loupart Wood, forming part of a strong defensive line which might have marked the limit of the German retreat. It was clear from that day onwards that the movement was not local but far reaching. The enemy was still too strong to be hustled, however, especially upon the northern sector of the operations, where Jacob’s Second Corps was feeling the German line along its whole front. An attempt at an advance at Bucquoy upon the night of March 13, carried out by the 137th Brigade of the Forty-sixth North Midland Division, met with a check, though most bravely attempted. The two battalions concerned, the 5th South Staffords and 5th North Staffords, found themselves entangled in the darkness amid uncut wire and suffered considerable loss before they could extricate themselves from an impossible position.

Fighting Line, February 24, 1917, and Fighting Line, March 1,1917

On March 19 and 20 the whole movement had become much more pronounced, and the French as well as the British were moving over a seventy-mile front, extending from Arras in the north to Soissons in the south. Each day now was a day of joy in France as some new strip of the fatherland was for a time recovered, but the joy was tempered by sorrow and anger as it was learned with what barbarity the Germans had conducted their retreat. To lay a country waste is no new thing in warfare. It has always been held to be an occasional military necessity though the best commander was he who used it least. In all Napoleon’s career it is difficult to recall an instance when he devastated a district. At the same time it must be admitted that it comes within the recognised chances of war, and that when Sherman’s army, for example, left a black weal across the South the pity of mankind was stirred but not its conscience. It was very different here. These devils — or to be more just — these devil-driven slaves, with a malignity for which it would be hard to find a parallel, endeavoured by every means at their command to ruin the country for the future as well as for the present. Buildings were universally destroyed, including in many cases the parish churches. Historical monuments, such as the venerable Castle of Coucy, were blown to pieces. Family vaults were violated and the graves profaned. The furniture of the most humble peasants was systematically broken. The wells were poisoned and polluted. Worst of all, the young fruit-trees were ringed so as to destroy them for future seasons. It was considered the last possibility of savagery when the Mahdi’s men cut down the slow-growing palm-trees in the district of Dongola, but every record upon earth has been swept away by the barbarians of Europe. As usual these outrages reacted upon the criminals, for they confirmed those grim resolutions of the Allies which made that peace by compromise for which the Germans were eternally working an absolute impossibility. Their Clausewitz had taught them that it is of supreme importance to make peace before there comes a turn of the tide, but he had not reckoned upon his descendants being so brutalised that a peace with them was a self-evident impossibility.