Delphi Complete Works of Sir Arthur Conan Doyle (Illustrated) (1385 page)

Read Delphi Complete Works of Sir Arthur Conan Doyle (Illustrated) Online

Authors: SIR ARTHUR CONAN DOYLE

On the morning of April

It is suggestive of the value of the tanks whether in German or in British hands that where the attack was unsupported by these machines it broke down under the British fire, as on the right of Gator’s Fifty-eighth Division to the south and on the left of the Eighth Division. There were fifteen German tanks in all, so their array was a formidable one, the more so in a mist which was impenetrable at fifty yards. It was for the British now to experience the thrill of helpless horror which these things can cause even in brave hearts when they loom up out of the haze in all their hideous power. The 2/4th Londons on the south of the village were driven back to the line Cachy — Hangard Wood, so that their neighbours of the 2/2nd London had to conform. The 2/ 10th London counter-attacked at once, however, and penetrated Hangard Wood, doing something to ease the situation. The 2nd Middlesex and 2nd West Yorks were overrun by the tanks, much as the Roman legionaries were by the elephants of Pyrrhus, and even the historical and self-immolating stab in the belly was useless against these monsters. The 2nd Rifle Brigade were also dislodged from their position and had to close up on the 2nd Berkshires on their left. The 2nd East Lancashires had also to fall back, but coming in touch with a section of the 20th Battery April 24. of divisional artillery they were able to rally and hold their ground all day with the backing of the guns.

The 2nd Devons in reserve upon the right were also attacked by tanks, the first of ‘which appeared suddenly before Battalion Headquarters and blew away the parapet. Others attacked the battalion, which was forced to move into the Bois d’Aquenne. There chanced to be three heavy British tanks, in this quarter, and they were at once ordered forward to restore the situation. Seven light whippet tanks were also given to the Fifty-eighth Division. These tanks then engaged the enemy’s fleet, and though two of the heavier and four of the light were put out of action they silenced the Germans and drove them back. With these powerful allies the infantry began to move forward again, and the 1st Sherwood Foresters carried out a particularly valuable advance.

Shortly after noon the 173rd Brigade of the Fifty-eighth Division saw the Germans massing behind tanks about

The Fifty-eighth had good neighbours upon their right in the shape of the Moroccan corps, a unit which is second to none in the French Army for attack. These were not engaged, but under the orders of General Debeney they closed up on the left so as to shorten the front of General Gator’s division, a great assistance with ranks so depleted. His troops were largely lads of eighteen sent out to fill the gaps made in the great battle, but nothing could exceed their spirit, though their endurance was not equal to their courage.

On the evening of April 24 General Butler could say with Desaix, “The battle is lost. There is time to win another one.” The Germans not only held Villers-Bretonneux, but they had taken Hangard from the French, and held all but the western edge of Hangard Wood. The farthest western point ever reached by the Germans on the Somme was on this day when they occupied for a time the Bois l’Abbé, from which they were driven in the afternoon by the 1st Sherwoods and 2nd West Yorks. They had not attained Cachy, which was their final objective, but none the less it was very necessary that Villers-Bretonneux and the ground around it should be regained instantly before the Germans took root.

For this purpose a night attack was planned on the evening of April 24, and was carried out with great success. The operation was important in itself, but even more so as the first sign of the turn of the tide which had run so long from east to west, and was soon to return with such resistless force from west to east.

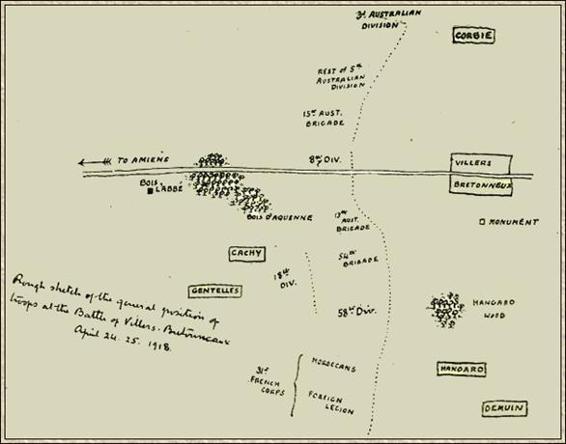

For the purposes of the attack the fresh 13th Australian Brigade (Glasgow) was placed under the General of the Eighth Division, and was ordered to attack to the south of Villers, while the 15th Australian Brigade made a similar advance upon the north. Each of these was directed to pass beyond the little town, which was to be cleared by an independent force. On the right of the Australians was the balance of the Eighth Division, which had to clear up the Bois d’Aquenne.

Rough sketch of the general position of troops at

the Battle of Villers-Bretonneux, April 24-25, 1918.

The attack was carried out at 10 P.M., the infantry having white arm-bands for identification in the darkness. There was no artillery preparation, and the advance was across unknown country, so that it may be placed among the most hazardous operations in the war. In the case of the 13th Australian Brigade, the 52nd Battalion was on the right in touch with the British, while the 51st was on the left, with the 50th in support. From the onset the machine-gun fire was very severe, especially against the 51st Regiment, but the admirable individuality of the Australian soldiers was of great service to them, every man getting forward through the darkness as best he could. The weather was ideal, for there was sufficient moon to give direction, but not enough to expose the troops to distant fire. The German flares were rather a help to the attack by defining the position. The Australian front got as far forward as Monument Wood, level with the village, but the 173rd Brigade on their right was in some difficulty, and they themselves were badly enfiladed from the town, so they could not maintain their more advanced position. The 2nd Northamptons, attached to the 13th Australian Brigade, had been told off to take the town itself, but both their colonel and their adjutant were killed during the assembly, and some confusion of orders caused the plans to miscarry. On the north of the town the 15th Australian Brigade, with the 22nd Durhams attached, had been an hour late in starting, but the 60th and 59th Regiments got up, after some confused fighting, to a point north of the town, which was entered after dawn and cleared up by the 2nd Berkshires, aided by a company of the Australian 58th Battalion. The The German tanks had done good work in the attack, and some of the British tanks were very useful in the counter-attacks, especially three which operated in the Bois d’Aquenne and broke down the obstinate German resistance in front of the Eighth Division. Daylight on April 25 found the British and Australian lines well up to the village on both sides, and a good deal of hard fighting, in which the troops got considerably mixed, took place. One unusual incident occurred as two blindfolded Germans under a flag of truce appeared in the British line, and were brought to Colonel Whitham of the 52nd Australian Regiment. They carried a note which ran: “My Commanding Officer has sent me to tell you that you are confronted by superior forces and surrounded on three sides. He desires to know whether you will surrender and avoid loss of life. If you do not he will blow you to pieces by turning his heavy artillery on to your trenches.” No answer was returned to this barefaced bluff, but the messengers were detained, as there was considerable doubt as to the efficiency of the bandages which covered their eyes.

By 4 P.M. on April 25 the village had been cleared, and the troops were approximately in the old front line. The 22nd Durham Light Infantry had mopped up the south side of the village. About a thousand prisoners had been secured. The 54th Brigade of Lee’s Eighteenth Division, which had been in support, joined in the fighting during the day, and helped to push the line forward, winning their way almost to their final objective south of the village and then having to yield

There was an aftermath of the battle on April 26 which led to some very barren and sanguinary fighting in which the losses were mainly incurred by our gallant Allies upon the right. There was a position called The Monument, immediately south of Villers, which had not yet been made good. The Moroccan Division had been slipped in on the British right, and their task was to assault the German line from this point to the north edge of Hangard Wood. Part of the Fifty-eighth Division was to attack the wood itself, while on the left the Eighth Division was to complete the clearance of Villers and to join up with the left of the Moroccans. The Eighth Division had already broken up three strong counter-attacks on the evening of April 25, and by the morning of April 26 their part of the programme was complete. The only six tanks available were given to the Moroccans. At 5:15 on the morning of April 26 the attack opened. It progressed well near the town, but on the right the Foreign Legion, the very cream of the fighting men of the French Army, were held by the murderous fire from the north edge of Hangard Wood. The 10th Essex and 7th West Kents, who had been lent to the Fifty-eighth Division’ by the 53rd Brigade, were held by the same fire, and were all mixed up with the adventurers of the Legion, the losses of both battalions, especially the West Kents, being terribly heavy. The Moroccan Tirailleurs in the centre were driven back by a German counter-attack, but were reinforced and came on again. Hangard village, however, held up the flank of the French. In the evening about half the wood was in the hands of the Allies, but it was an inconclusive and very expensive day.

The battle of Villers-Bretonneux was a very important engagement, as it clearly defined the

ne plus ultra

of the German advance in the Somme valley, and marked a stable equilibrium which was soon to turn into an eastward movement. It was in itself a most interesting fight, as the numbers were not very unequal. The Germans had five divisions engaged, the Fourth Guards, Two hundred and twenty-eighth. Two hundred and forty-third. Seventy-seventh Reserve, and Two hundred and eighth. The British had the Eighth, Fifty-eighth, Eighteenth, and Fifth Australian, all of them very worn, but the Germans may also have been below strength. The tanks were equally divided. The result was not a decided success for any one, since the line ended much as it had begun, but it showed the Germans that, putting out all their effort, they could get no farther. How desperate was the fight may be judged by the losses which, apart from the Australians, amounted to more than 9000 men in the three British divisions, the Fifty-eighth and Eighth being the chief sufferers.

As this was the first occasion upon which the Germans seem to have brought their tanks into the line of battle, some remarks as to the progress of this British innovation may not be out of place — the more so as it became more and more one of the deciding factors in the war. On this particular date the German tanks were found to be slow and cumbrous, but were heavily armed and seemed to possess novel features, as one of them advanced in the original attack upon April 24 squirting out jets of lachrymatory gas on each side. The result of the fighting next day was that two weak (female) British tanks were knocked out by the Germans while one German tank was destroyed and three scattered by a male British tank. The swift British whippet tanks were used for the first time upon April 24, and seem to have acted much like Boadicea’s chariots, cutting a swathe in the enemy ranks and returning crimson with blood.

Treating the subject more generally, it may be said that the limited success .attained by tanks in the shell-pocked ground of the Somme and the mud of Flanders had caused the Germans and also some of our own high authorities to underrate their power and their possibilities of development. All this was suddenly changed by the battle of Cambrai, when the Germans were terrified at the easy conquest of the Hindenburg Line. They then began to build. It may be said, however, that they never really gauged the value of the idea, being obsessed by the thought that no good military thing could come out of England. Thus when in the great final advance the tanks began to play an absolutely vital part they paid the usual price of blindness and arrogance, finding a weapon turned upon them for which they had no adequate shield. If any particular set of men can be said more than another to have ruined the German Empire and changed the history of the world, it is those who perfected the tank in England, and also those at the German headquarters who lacked the imagination to see its possibilities. So terrified were the Germans of tanks at the end of the war that their whole artillery was directed to knocking them out, to the very great relief of the long-suffering infantry.