Delphi Works of Ford Madox Ford (Illustrated) (211 page)

Read Delphi Works of Ford Madox Ford (Illustrated) Online

Authors: Ford Madox Ford

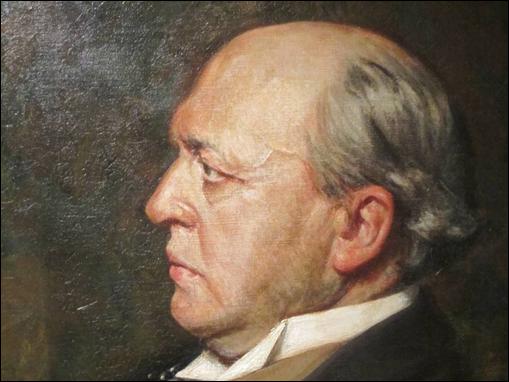

Henry James (1843-1916), the leading novelist of his time, was a source of inspiration to Ford, who received help from the great matser during his early years as a novelist.

CONTENTS

TO

FRAU REGIERUNGSRAT

EMMA GOESEN

WHO RETURNED FROM NEW YORK MORE THAN A GENERATION AGO AND HAS SINCE BEATEN THE AUTHOR THIRTY-ONE TIMES OUT OF THIRTY-TWO GAMES OF CHESS

THIS WITH AFFECTION

THE first thing he said when she came into the room was:

“My father

is

dead,” and the announcement stayed her at the door, her hands falling to her side, open, as if, though a moment before they would have known their place and have lain upon the two shoulders of the man she was to marry, now, so new a creature did this announcement make him seem, that she had, at least for a moment, to hesitate as to whether he could still belong to her. It was under the definite spell of that feeling that she uttered the words:

“Oh dear!” — words that implied more than anything else—” tell me all: tell me the worst!”

And he was so sensitive to her moods that he, too, neither made to take her into his arms nor to utter an endearment.

“I

am

the richest citizen in the world, for what it’s worth,” he said, with a flavour of scorn, as if he were quoting the words of a man for whom he had an infinite contempt.

She sank down upon one of the hard-seated, fine, mahogany chairs before she uttered the word “How — !” But she was unable to furnish any adjective. The situation was beyond her: she could say neither “How tremendous!”

“How terrible!” nor yet “How magnificent!”

You may guess at a person’s character very efficiently by considering his first abstract remark upon any given happening. Tall, rather dark, with rounded cheeks, hair arranged high on her head, tight-fitting park dress, and a slow, elastic gait, and with her self-control and her clear lines — she was called Eleanor Greville — you could not deny the epithet “fine” to her, or to the room or to the atmosphere that surrounded her. And four days before she would at least have been ready to give as much insight into her personality: she would at least have been able to utter some moralisation if she had heard that overwhelming wealth had fallen to the share of any of her intimates.

But, from the Monday on which the first news of his father’s death had been cabled from across the water, she had seemed to be lifted out of contact with her own personality. The death had been denied on Tuesday, re-affirmed on the Wednesday by indignant Transatlantic journalists, and redenied on the Thursday by vastly more indignant Wall Street authorities, who claimed to have “seen him” the night before. So that she had not known whether it would be necessary for her to face the new position, terrible or beneficent, till that moment. She had not faced it: neither had he given her any assistance.

He had explained to her that the report of his father’s death might be true: it might be just the discovery of a genuine newspaper-writer anxious to provide his journal with the earliest report of a good “story.” Or it might be a lie invented by his father’s enemies who desired to “bear” his father’s interests. Or it might be a lie spread abroad by his father himself. And he had explained to her how it might be made to suit his father’s turn to “bear” his own interests. She was not lacking in intelligence sufficient to grasp the idea of such a manoeuvre, if she had not an exact knowledge, beforehand, of how it would be worked. She was shut off by the necessity of her life with a father who was called “trying” by most people who knew him — a father whose death, if it might have caused some satisfaction to a world that sent a certain class of learned books out for “review,” would certainly not have sent the prices of varied stocks tumbling down all over the world.

For the mere rumour of her lover’s father’s death — the rumour thus unconfirmed, denied, re-affirmed and re-denied with violent asseverations — had undoubtedly effected that. She knew it from her Cousin Augustus, who, a solicitor with a too-limited capital, had, upon the very Monday night, dashed down from town to get from her, with cousinly force, some sort of what he called “pointer.” Things, he said, were “falling” all over the place: they went down in London and they went down in Yokohama. As for what things were doing in the continent that lies westward, between London and Yokohama, he said the report of it beggared description. It had given to her belief in human nature one severe shaking at least. Her Aunt Emmeline, a lady of fifty-two, dessicated and thin-lipped, who more than any of the family had been able to indicate by dogged silence a disapproval of her engagement to “an American” — though to be sure you could not possibly have told that this particular American was anything but a very gentle and unassuming anybody else — her Aunt Emmeline had come to her between tears and outraged indignation to assure her that if Eleanor’s lover’s father

were

dead she would be literally beggared.

It put a new light upon the fact — she had discovered it whilst her aunt had been spending last Christmas with them — that her aunt received by post a journal called the

Investor’s Guide.

No one had ever exactly known how her Aunt Emmeline’s money had been invested: one associated her so definitely with a family solicitor’s advice: she took her needs to be so small that it was incredible that she should have tried speculation — and speculation of the wildest sort.

It came, in fact, to this quiet girl of thirty or so as a revelation — as the shock of an earthquake might have done. It revealed to her her aunt as possessed of a perfect abyss of cupidity — though she could not in the least imagine what she would propose to do with money when she had it. It had worried her, too — this revelation — because it seemed to show that the influence of her lover’s father had spread from the town with a queer name where he resided even to the decorous and quite ordinary Red Hill, where her aunt’s creeper-bedecked villa offered a small white drive to the impeccable suburban street.

For her aunt had announced that since Eleanor’s engagement she had decided to follow the fortunes of the Charles Collar Kelleg companies: she had speculated in the shares of the enterprises that — according to the

Investor’s Guide

— C. Collar Kelleg sustained with his voice from Kellegville, Ma. It was not enough for her to say to her aunt that her lover dissociated himself from his father, his father’s enterprises, and — as far as he decently could — from his father’s State. It did not even mitigate her aunt’s wrath when Eleanor said that she herself, in the course of her long intimacy with the son, had only four times heard him mention his father’s name. Her aunt had the crushing reply that if her

fiancé

had not been his father’s son she would never have let herself be drawn into speculating — on the cover system — in the Kelleg group of companies.

That announcement had, in a sense, relieved the girl’s mind. It meant that her aunt might be a solitary speculator on this side of the water. For of late so considerably had the name of Collar Kelleg figured in the world as that of an engineer of combines, a breaker of American railway laws, or an amateur of the Fine Arts, that she had come to fear that each inhabitant of each ivy-covered house that she called on in Canterbury, Kent, England, was concerned in the fate of — was certain to be ruined by — C. Collar Kelleg, of Kellegville, Ma., U.S.A. Only a fortnight before she had taken her lover to a garden-party at one of the Canons’ houses. And when she had introduced him to the Canon himself, the Canon — a wearied-looking cleric with side whiskers and a not too new coat, a clergyman reported to be in difficulties even with his butcher — the Canon had said:

“Not really a relation of — of

the

Collar Kelleg?” And when her lover had winced, when making the confession of a relationship that he always left undefined, the Canon, exhibiting at once a latent eagerness and an ostentatious official indifference, had asked:

“And is it true that he... that your uncle, is it? ... meditates buying up... acquiring an interest in... all our railway lines between... Liverpool and the Metropolis?”

The young man had answered:

“Why: you cannot tell.

I

cannot. Of course there are so many things that he controls. He might want to send them backwards and forwards between New York and London. And Liverpool’s on the way between, of course.”

The Canon had choked in his throat at these words, to which he seemed to accord a huge gravity, and she had been conscious that, in and out among the clumps of cedars on that sunny lawn, no person ever spoke to the Canon that afternoon without hurrying away to another group of guests with an announcement that caused heads to turn in their direction. It affected her to a pitch of nervousness — so that for a moment or two she was relieved when her lover was disengaged by a lady with a pink dress and a pleasant laugh. She stood alone by a clump of hydrangeas waiting for him to rejoin her, and a voice behind her back uttered:

“Oh, I suppose he’s come down to see if he won’t buy the cathedral.”

And another:

“Oh, he

couldn’t

do that, could he? Doesn’t it belong to the State or something?”

She felt herself grow warm from her feet to the roots of her hair, and she hurried aimlessly away as the first voice exclaimed:

“Yes. That’s the point of my joke. Thank goodness here’s

one

thing these fellows can’t…”

She hurried away — aimlessly. The Canon’s garden had such high walls that it seemed to her, precisely, that what she wanted to do was to sink into the ground. If only her lover had not been Collar Kelleg! He had every other possible quality — stability, kindness, gentleness, the right brown eyes, the right full voice, the right brown moustache, the right great height. It was only his portentous identity that jarred on the perfection of the afternoon. For the grass was so green that the tall cedars appeared dark blue: the garden was full of pleasant people: the high, brick walls gave a comforting feeling of privacy; the tallest, square tower of the cathedral peered down upon them, almost golden in the sunlight, benignly, like a great benediction from many tranquil ages. It ought to have been such a perfect afternoon, that on which she introduced her lover to her people, for if they were not — the Canon’s guests — her own family, they were, very exactly, her clan; some very rich, some decently poor, some very clerical, some decently scholarly, some with great estates, some with great mortgages — but all, down to the red-haired archdeacon from a northern diocese, all quiet, unobtrusive and presentable after you made allowances. And she, if she were the handsomest girl there, was not very noticeably so. She would not have wanted more.

It was only her lover who stood out, by reason of a portentous name. And she found herself explaining to several intimately sympathetic ladies that he was not really at all closely connected to

the

Mr Collar Kelleg; that they were not in communication with one another; that her

fiancé

had not been in America for fifteen years; that he all but made his own living; that, in fact, you could hardly call him American at all. And she tried to put it, as unobtrusively as possible, that, if his means would run to it, they intended to settle down in one of the little, old, good houses near the City and live as a nice young couple should. To the objection that her father would miss her a great deal she went even so far as to hazard that they might settle down with him at the end of the two years or so that their engagement would last. Only of course it was awkward that her

fiancé

needed a studio. Her father would not feel inclined to sacrifice a greenhouse or part of his garden in which to build a shed with a north light.

It had not been through any lack of veracity that she had so painted the probable course of their future. It had so presented itself to her: her lover, even, had so projected it. He too loved that simple, tranquil, fine life: he loved, that is to say, the outward aspects of it: the broad, smooth downs, the gently-aged houses, the dependable servants, the quiet, filled streets, the soft colours. It was he even who suggested that they might share the house with her father. He could not imagine a better-ordered type of life. There was only London that was finer — and they could go up to London as often as they pleased. The only obstacle was that her father had a blind prejudice against Americans — against the American point of view: against the American scholarship: against the very name. He went so far — he, the politest of men, who had put no obstacle but muteness against her engagement — went so far as to say that he would discharge his servants, pack up his books and go back to Cambridge before ever an American should take up permanent lodgings in his house. He had never met an American before he met her

fiancé;

but he changed none of his views when he did meet him.

Nevertheless, until that fatal Monday when the papers had suddenly — with special cables — announced the death of Charles Collar Kelleg, she had to herself, as to all her relations and friends, mitigated her lover’s Americanism, and she and he together had speculated upon which of the many pleasing houses near the ancient valley city should eventually hold them and witness their unobtrusive joys.