Delphi Works of Ford Madox Ford (Illustrated) (282 page)

Read Delphi Works of Ford Madox Ford (Illustrated) Online

Authors: Ford Madox Ford

Moved by the desire to tell her husband, Frances Milne went into the next room, and whilst she was there it chanced that for the third or fourth time Mrs. Lympere came to the door. Tall and dark, with her large eyes suddenly filling with desire and hope, she lifted minutely her white gloves.

“Oh, come with me!” she said. “I have wanted to speak to you for so long.”

“Assuredly I will come where you will,” he answered. And when Frances Milne came out from the room where her husband smiled in his sleep she heard only the sound of a happy voice on the stairs.

THE END

A ROMANCE OF THE OLD WORLD

Initially appearing in 1911, this historical novel concerns Henry Hudson’s 1609 voyage across the Atlantic, which led to the discovery of the river named after him. The novel is a study of America, analysing its passage through time, and also portraying the supernatural subject of black magic.

The ‘Half Moon’

is principally an adventure novel, with typical suspense features, including hidden treasure, a mutiny on a ship, dangerous ‘savages’ and scenes of violence.

The novel introduces the character Edward Colman, a builder of merchant ships, wearied of the Old World’s corruption and religious persecution.

Forced to flee his home in the Ancient Kentish town of Rye, Coleman travels to Amsterdam and joins the crew of Hudson’s ship the ‘Half Moon’, acting as the interpreter for the English captain’s Dutch crew.

On board the ship, Colman rejects the advances of Anne Jeal, a proud magician who uses her dark powers to ensnare him and disrupt the Avalon’s journey.

Through Colman’s character, Ford presents a personification of New York and its future industrial nature.

At one point of the novel, Colman glimpses an island, foreseeing a city that will rise from the water — the future Manhattan.

The ‘Half Moon’

is a compelling tale, with diverse characters, well-handled shifts in narration, all spiced with the intriguing elements of historical novel.

The first edition

CONTENTS

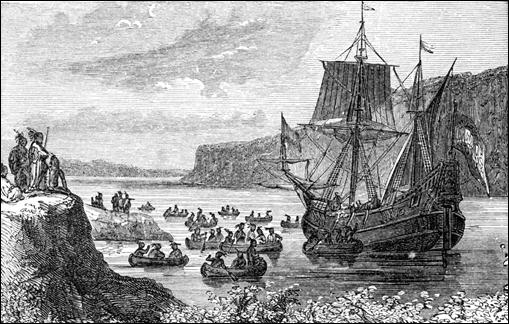

Henry Hudson (c. 1560 – 1611) was an English explorer and navigator.

Hudson’s ship the ‘Halve Maen’ in the Hudson River.

THE ‘HALF MOON’

A ROMANCE OF THE OLD WORLD AND THE NEW

“Come I let us take ship and sail unto that Avalon where there is no longer any ill

.” — How they Quested.

DEDICATION

To

W. A. BRADLEY, ESQ.

Winchelsea, June

8th

,

1907.

MY DEAR BRADLEY,

Since it was you who, on a fine day and a noble stream, suggested to me the subject of this book, you must accept this dedication. I write it on a day as fine beside the blue water of the narrow seas from which, three hundred years ago, the good men and true sailed out to find your river.

Turning your suggestion over in my mind — for, whilst we sailed up the Hudson, you suggested that I should write a story about the voyage of the

Half Moon

— I grew a little diffident. For, when you come to think of it, a voyage is not a very inspiring thing to write about — even when it is a voyage to a new world. Then there came to me the obvious thought that, what is inspiring about a voyage or a world is the passion that gave rise to the one and the other. For it is not the seas but the men who cross them; not the hills but the men who live on them and in time mould their surfaces; not the rivers but the hearts of the men who sail upon them, that are the subjects of human interest. Just as America would be nothing without you and your countrymen, so the voyage of the

Half Moon

would have been just a bit of seafaring without the passions of Hudson and his comrades. The proper study of mankind, in fact, is man.

And, since your portion of the New World was, to all intents and purposes, uninhabited at the date of the voyage of the

Half Moon,

so I was forced to cast my eyes back to the Old World and its men. You have an ingenious American riddle which I have never understood, but one which has always impressed me, “Why is a hero?” — I don’t know. But it struck me that the answer to the question, “Why did the New World attract?” might, if one were skilful enough, be answered.

And in the

Half Moon

I have tried to answer it.

Fortunately for me the psychology of the Old World in the days of Hudson has always been very fascinating to me. It is, as you know, the subject to which I have more than anything devoted my attention: for at that date the Dark Ages were finally breaking up. There lingered many traces of that darkness; a thousand superstitions, a million old beliefs. But men were beginning to disbelieve — and in consequence men were beginning to look out for truths of all kinds: for new faiths, for new methods of government and, perhaps above all, for lands in which Utopias might be found or might be founded.

So that it was a comparatively easy task for me to shadow forth one of the chief causes for the voyage of the

Half Moon

— for, by the time of James I of England men went to the New World almost more in search of places where freedom might be found, than for gold and spices as before they had done. They were driven forth from Europe by foolish laws, like that of “owling” ; by the desire to be free from superstitions, like that of witchcraft; by intrigues, oppressions, poverty and intolerance.

My task became easier still when I found that Colman, the first European to die between the shores of the Hudson River, was a freeman of Rye — of that quarter of the world which I know and love best. For you could not have a better object lesson than Rye, in the seventeenth century, of what it was that made America. Rye then had many privileges that had descended to it from the Middle Ages; it had, like its sister towns of the Cinque Ports, its own laws, its own rights, its own nobility, quite apart from those of the rest of England. These laws and privileges pressed heavily on the poorer inhabitants and caused much unrest and discontent. Rye, too, had been almost depopulated by the Plague in the days of Queen Elizabeth, and, in consequence, a whole population of foreign Protestants, Dutch, German and Huguenot, had been given leave to settle in Rye and around the walls.

And these foreign Protestants had, in the course of a generation, made many converts to their own form of faith, and had evolved that peculiar type that is now so famous — the Puritan. These Puritans in the days of James I were already being oppressed by the townsmen and by the King’s will — and it was only a few years later that the first ship’s company of them set sail for your New World.

And to show you how close is the traditional binding together of your great cities and our very little ones, I may say that our legend has it that the seats in Winchelsea church were made out of wood brought back by the

Mayflower.

I do not know how that may be — but certainly some of these seats are made of Tulip wood, which is no European wood. And certainly to-day, too, you will find that for every Churchman in this town there are five Nonconformists, so that the Puritan strain is still in the blood.

A word as to Edward Colman and Anne Jeal.

She stood at her window that looked right down the rocky heights of the town on to the quays and over the grey flats to the sea. And it came into her head to wonder if, by gazing at him for a long time, she could cause his eyes to rise up to hers. He was very busied with his little cogger, the

Anne Jeal:

for, the export of wool from King James’s England being, under pain of fine and death, forbidden, and the little

Anne Jeal

being used, more than anything, for the export of wool from the coast of Kent to the Low Countries, it behoved the young man to change, from time to time, the colouring of her bulwarks, the devices upon her sails and the gilded carvings on the little crenellated castles at her bow and stern. For in those days there were informers abroad, and if the town of Rye, by occasion of its status in the kingdom, were a very safe harbour, it was, by reason of its very Dutch population, a place full of men without honour or compunction.

The town of Rye had at that date more of Dutch and French Protestants than it had of English, and the Dutch still remained Dutch enough, though it was thirty years since the plague had swept the town almost bare of English, and the late Queen had assigned it as a place of residence for foreign Protestants. The worshipful powers of the town were still in the hands of men nominally English; there was not upon the council one man of a Dutch name; there wasn’t, among the barons or the jurats, a single Frenchman. Nevertheless, there was hardly a young man in the town but had a foreign mother — and Anne Jeal herself, who stood attiring herself in her window and looking down into the harbour, if she were the daughter of the Mayor of Rye, was the daughter of a French woman escaped from Paris after the massacre, and the grand-daughter of a strange Spanish woman come from Granada and reported to be of the Moorish faith, before her father — Anne Jeal’s great-grandfather — had taken refuge in the port. But she was a young woman, very passionate, hard browed and insolent, and, for all her foreign blood which gave her affrighting impulses, she was one of the first to call out upon the strangers that filled Rye town. She called them dirty, slow-witted, craven, liverless, heretical and Puritan, and if her father, the mayor, moved always in the council for acts that should tell hardly upon the foreigners, it was as much because his passionate daughter forced him to it, at home in the evenings, as because, by the light of day, he desired to limit the industries of folk who brought a good store of taxable commodities to the town.

But if he and the elder jurats and barons of the council desired these voiceless men — for as far as the town and port went they had no voice — to prosper and wax fat and very taxable, the younger folk were all for driving them out of the town altogether and taking their looms and their bacon curings, their glove skin tanneries and their herb-drying yards into their own hands.

At that date — in the year of our Lord 1609 — these things had reached a great height and a great heat. There was no doubt that, upon the whole, the French and the Dutch were very wealthy; there was equally no doubt that the council of the town had, in the two years’ mayoralty of Anne Jeal’s father, grown hard and hot upon the foreigners. They had passed orders that no house in the town should hold more than one woollen loom, or two for making cambric, and this pressed heavily upon the French and harder still upon the Dutch; they had passed an ordinance that no swine should pasture in the streets, and this was ill to bear for the Westphalian Anabaptists, who had brought with them from the town of Münster the trade of pig-curing; they had enacted that no compound of herbs should be infused for odours or remedies, save when the secret of the compounds was made known to the English leeches and barber surgeons that were barons of the ancient town. This was said to be for the avoidance of sorceries and enchantments. But, amongst the foreigners whose secrets, if the Act were observed, must thus pass into the hands of rivals, it was taken as especially evil that this observance should have been enacted by the father of Anne Jeal — for was not Anne Jeal, who descended from a Morisco, known to have powers that, along with her beauty, made her the most feared wench in the Five Ports? It was said — and it was quite currently believed — that her white skin, the carmine of her cheeks, the glitter of her black eyes, and the gold streaks in her black hair were due not to the properties of cosmetics, the recipe of which she had from her French mother, nor to the light of the sun and the breezes from heaven, but to vigils in the moonlight in the churchyard on certain nights at the turn of that luminary — on certain nights known only to Moors and Jews and the like. For the elder Dutchwomen of the town recorded she had been a very ill-favoured brat.

They said, too, that she had love philtres: that they would say, for she had every youth in the town at her beck and call — every youth that had ever broken bread at her father’s house. That proved that she had love philtres, for she made the bread herself. It proved, too, that she was monstrous disdainful, for she allowed in her father’s house no one that was not a baron’s son, a freeholder of a hundred pounds and upwards from the Foreign, or a master of a ship of forty tons and upwards. It was very lawful to believe in witchcraft, for did not the King James himself praise those who smelt out witches? And if the King James himself were no proper Englishman but a Scot, what was that to the Dutchmen of Rye? It pressed a little on the jurats and barons though.

On the other hand, such as by reason of a natural perversity were inclined to believe that witchcraft was a matter restricted to distinguished practitioners such as the Soldan, the Witch of Endor or the late Oxenham of Bude, who had made water to flow uphill in the sight of all men — such as argued that witchcraft was limited to the old, the wrinkled or the hideous had it in their favour that Anne Jeal set the teeth watering of youths — and of several old men — who had never passed her father’s door. They had it, too, in their favour — these doubters — that the very lad after whom it was known to all the town that Anne Jeal’s teeth watered — Edward Colman, whose father had been nineteen times mayor and whose ancestors had owned ships in Rye and taken pilgrims to Compostella ever since the days of King Alfred — Edward Colman hankered after the daughter of the Pfarrherr Koop. Nay, more, the daughter of Pfarrherr Koop hankered after Edward Colman, and every evening of the week you might see Edward Colman and Magdalena Koop sit, side by side silent, after the Dutch fashion, on the door-sill of the Pfarrherr’s cottage, in the Foreign, just beyond the walls of Rye.

It could not, the one part argued, be said that Anne Jeal had love philtres to put in her bread, if she could not keep to herself a youth who had eaten bread in her father’s house at the least three times a week since he had been four years of age. But, those of the other side said that undoubtedly — since in his younger days Edward Colman had passed so many days with her and since, over (our years before, he had called his last built cogger

Anne Jeal

and had, by all the town, been set aside and earmarked for Anne Jeal — undoubtedly it could not be argued that Anne Jeal had not used her philtres upon Edward Colman. Only — witch warred with witch — and it was to be observed that Edward Colman had never been the same to Anne Jeal since the night he had been, on a visit, connected with the illicit trade of wool, to the deserted chapel of the mad maid of Kent, our Lady of Court-at-Street. It was known that, in coming from Sandwich, that other Cinque Port, where Pfarrherr Koop had been sub-Pfarrherr to the Dutch Church, the Pfarrherr and his daughter had lain at Court-at-Street, and in a house down the knoll, by the old chapel, there dwelt a very wise woman. Magdalena Koop was a silent Dutch piece, but her nose was not an ell long; she could see to the end of it. A Dutch gilder bestowed upon a wise woman near a deserted chapel of the Old Faith — wouldn’t that buy a philtre as strong as any of Anne Jeal’s?

It is — and I suppose it must remain — a question whether Colman died in Sandy Hook or on the site of what is now New York. If I have inclined to the latter theory it is as much because I like to, as for any other reason. I like to. For a city is rendered impressive and holy by its graves; and I like to think that the grave of this first idealist to die in your great and bewildering city which so attracts and excites and charms me — that this grave of a searcher after the future, should be somewhere, let us say, between Madison Square and the ferries that for ever cross and recross the river that bears the Navigator’s name.