Delphi Works of Ford Madox Ford (Illustrated) (652 page)

Read Delphi Works of Ford Madox Ford (Illustrated) Online

Authors: Ford Madox Ford

“Did you ever have to do with a sick farm labourer? Those fellows! Why, they fold their hands and die for a touch of liver. Their life doesn’t hold them because it contains no interest. Half their healthy hours are spent in mooning and brooding: they all suffer from dyspepsia because of their abominable diet of cheese and tea. Why, I’d rather attend fifty London street rats with half a lung apiece than one great hulking farm bailiff. Those are the fellows, after all, the London scaramouches, for getting over an illness.

“Don’t you see, my dear sir, your problem is to breed disease-resisting men, and you won’t do it from men who mope about fields and hedges. No! modern life is a question of towns. Purify them if you can: get rid of smoke and foul air if you can. But breed a race fitted to inhabit them in any case.”

That indeed is the problem which is set before London — the apotheosis of modern life. For there is no ignoring the fact that mankind elects to live in crowds. If London can evolve a town type London will be justified of its existence. In these great movements of mortality the preacher and the moralist are powerless. If a fitted race can be bred, a race will survive, multiply and carry on vast cities. If no such race arrive the city must die. For, sooner or late, the drain upon the counties must cease: there will no fresh blood to infuse. If it be possible, in these great rule of thumb congeries, “sanitary conditions” must be enforced; rookeries must be cleared out; so many cubic feet of air must be ensured for each individual. (And it must be remembered that, for the Christian era, this is a new problem. No occidental cities, great in the modern sense, have existed, none have begun to exist until the beginning of the Commercial Ages. The problem is so very young that we have only just begun to turn our attention to it.)

But, if the rest that comes with extinction is not to be the ultimate lot of London, the problem must solve itself either here or there — in the evolution either of a healthy city or of a race with a strong hold upon life. We know that equatorial swamps have evolved tribes, short legged, web-footed, fitted to live in damp, in filth, in perpetual miasmas. There is no reason therefore why London should not do as much for her children. That would indeed be her justification, the apology for her existence.

The creatures of the future will come only when our London indeed is at rest. And, be they large-headed, short legged, narrow-chested, and, by our standards, hideous and miserable, no doubt they will find among themselves women to wive with, men to love and dispute for, joys, sorrows, associations, Great Figures, histories — a London of their own, graves of their own, and rest. Our standards will no longer prevail, our loves will be dead; it will scarcely matter much to us whether Westminster Abbey stand or be pulled down: it will scarcely matter to us whether the portraits of our loves be jeered at as we jeer at the portraits of the loves, wives, mistresses and concubines of Henry VIII. Some of us seek to govern the Future: may their work prosper in their hands; some of us seek to revive, to bathe in, the spirit of the Past: surely great London will still, during their lives, hold old courts, old stones, old stories, old memories. Some of us seek relief from our cares in looking upon the present of our times. We may be sure that to these unambitious, to these humble, to these natural men, who sustain their own lives through the joys, the sorrows, and the personalities of the mortal creatures that pass them in the street, wait upon them at table, deliver their morning bread, stand next to them in public-house bars — to these London with its vastness that will last their day, will grant the solace of unceasing mortals to be interested in.

In the end we must all leave London; for all of us it must be again London from a distance, whether it be a distance of six feet underground, or whether we go to rest somewhere on the other side of the hills that ring in this great river basin. For us, at least, London, its problems, its past, its future, will be at rest. At nights the great blaze will shine up at the clouds; on the sky there will still be that brooding and enigmatic glow, as if London with a great ambition strove to grasp at Heaven with arms that are shafts of light. That is London writing its name upon the clouds.

And in the hearts of its children it will still be something like a cloud — a cloud of little experiences, of little personal impressions, of small, futile things that, seen in moments of stress and anguish, have significances so tremendous and meanings so poignant A cloud — as it were of the dust of men’s lives.

THE END

TS

AND CERTAIN NEW REFLECTIONS: BEING THE MEMORIES OF A YOUNG MAN

First published in 1910 when Ford was thirty-seven years old, this was to be the first of several memoirs he wrote during his mid to late literary career.

Ancient Lights

concerns the author’s youth, growing up as the grandchild of the famous artist Ford Madox Brown, detailing the lives of other members of the Pre-Raphaelite circle that the young Ford came into contact with. One of his most vivid childhood memories was of offering the Russian master Turgenev a chair to sit on at a literary soiree. The memoir also concerns Ford’s cousins the Rossettis, who were precocious anarchists. Through these kinsmen, Ford met Russian political émigrés such as Prince Kropotkin.

The original title page

CONTENTS

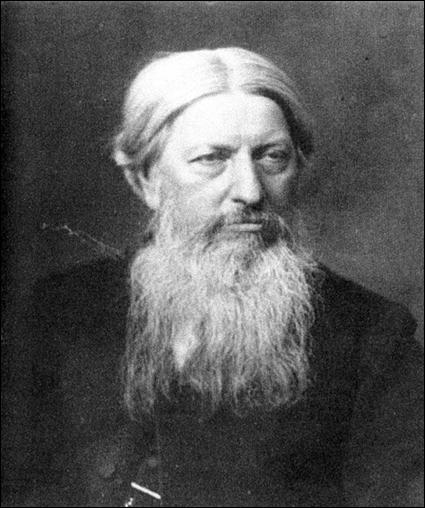

Ford’s grandfather Ford Madox Brown (1821–1893) was a central figure of the author’s early years

DEDICATION

TO CHRISTINA AND KATHARINE

MY DEAR KIDS,

Accept this book, the best Christmas present that I can give you. You will have received before this comes to be printed, or at any rate before — bound, numbered and presumably indexed — it will have come in book form into your hands — you will have received the amber necklaces, and the other things that are the outward and visible sign of the presence of Christmas. But certain other things underlie all the presents that a father makes to his children. Thus there is the spiritual gift of heredity.

It is with some such idea in my head — with the idea, that is to say, of analysing for your benefit what my heredity had to bestow upon you that I began this book. That of course would be no reason for making it a “book,” which is a thing that should appeal to many thousands of people, if the appeal can only reach them. But, to tell you the strict truth, I made for myself the somewhat singular discovery that I can only be said to have grown up a very short time ago — perhaps three months, perhaps six. I discovered that I had grown up only when I discovered quite suddenly that I was forgetting my own childhood. My own childhood was a thing so vivid that it certainly influenced me, that it certainly rendered me timid, incapable of self-assertion, and as it were perpetually conscious of original sin until only just the other day. For you ought to consider that upon the one hand as a child I was very severely disciplined, and when I was not being severely disciplined I moved amongst somewhat distinguished people who all appeared to me to be morally and physically twenty-five feet high. The earliest thing that I can remember is this, and the odd thing is that, as I remember it, I seem to be looking at myself from outside. I see myself a very tiny child in a long blue pinafore looking into the breeding-box of some Barbary ringdoves that my grandmother kept in the window of the huge studio in Fitzroy Square. The window itself appears to me to be as high as a house and I myself to be as small as a doorstep, so that I stand on tiptoe, and just manage to get my eyes and nose over the edge of the box whilst my long curls fall forward and tickle my nose. And then I perceive greyish and almost shapeless objects with, upon them, little speckles, like the very short spines of hedgehogs, and I stand with the first surprise of my life and with the first wonder of my life. I ask myself: can these be doves? — these unrecognizable, panting morsels of flesh. And then, very soon, my grandmother comes in and is angry. She tells me that if the mother dove is disturbed she will eat her young. This I believe is quite incorrect. Nevertheless I know quite well that for many days afterwards I thought I had destroyed life and that I was exceedingly sinful. I never knew my grandmother to be angry again except once when she thought I had broken a comb which I had certainly not broken. I never knew her raise her voice, I hardly know how she can have expressed anger; she was by so far the most equable and gentle person I have ever known that she seemed to be almost not a personality but just a natural thing. Yet it was my misfortune to have from this gentle personality my first conviction — and this, my first conscious conviction was one of great sin, of a deep criminality. Similarly with my father, who was a man of great rectitude and with strong ideas of discipline. Yet for a man of his date he must have been quite mild in his treatment of his children. In his bringing-up, such was the attitude of parents towards children that it was the duty of himself and his brothers and sisters at the end of each meal to kneel down and kiss the hands of their father and mother as a token of thanks for the nourishment received. So that he was after his lights a mild and reasonable man to his children. Nevertheless, what I remember of him most was that he called me “the patient but extremely stupid donkey.” And so I went through life until only just the other day with the conviction of extreme sinfulness and of extreme stupidity.

God knows that the lesson we learn from life is that our very existence in the nature of things is a perpetual harming of somebody — if only because every mouthful of food that we eat a mouthful taken from somebody else. This lesson you will have to learn in time. But if I write this book, and if I give it to the world, it is very much that you may be spared a great many of the quite unnecessary tortures that were mine until I “grew up.” Knowing you as I do, I imagine that you very much resemble myself in temperament and so you may resemble myself in moral tortures; and since I cannot flatter myself that either you or I are very exceptional, it is possible that this book may be useful, not only to you for whom I have written it, but to many other children in a world that is sometimes unnecessarily sad. It sums up the impressions that I have received in a quarter of a century. For the reason that I have given you — for the reason that I have now discovered myself to have “grown up,” it seems to me that it marks the end of an epoch, the closing of a door.

As I have said, I find that my impressions of the early and rather noteworthy persons amongst whom my childhood was passed — that these impressions are beginning to grow a little dim. So I have tried to rescue them now before they go out of my mind altogether. And, whilst trying to rescue them, I have tried to compare them with my impressions of the world as it is at the present day. As you will see when you get to the last chapter of the book, I am perfectly contented with the world of to-day. It is not the world of twenty-five years ago, but it is a very good world. It is not so full of the lights of individualities, but it is not so full of shadow for the obscure. For you must remember that I always considered myself to be the most obscure of obscure persons — a very small, a very sinful, a very stupid child. And for such persons the world of twenty-five years ago was rather a dismal place. You see there were in those days a number of those terrible and forbidding things — the Victorian great figures. To me life was simply not worth living because of the existence of Carlyle, of Mr. Ruskin, of Mr. Holman Hunt, of Mr. Browning, or of the gentleman who built the Crystal Palace. These people were perpetually held up to me as standing upon unattainable heights, and at the same time I was perpetually being told that if I could not attain to these heights I might just as well not cumber the earth. What then was left for me? Nothing. Simply nothing.

Now, my dear children — and I speak not only to you but to all who have never grown up — never let yourselves be disheartened or saddened by such thoughts. Do not, that is to say, desire to be Ruskins or Carlyles. Do not desire to be Ancient Lights It will crush in you all ambition; it will render you timid, it will foil nearly all your efforts. Nowadays we have no great figures and I thank Heaven for it, because you and I can breathe freely. With the passing the other day of Tolstoy, with the death just a few weeks before of Mr. Holman Hunt, they all went away to Olympus where very fittingly they may dwell. And so you are freed from these burdens which so heavily and for so long hung upon the shoulders of one, and of how many others? For the heart of another is a dark forest, and I do not know how many thousands of other my fellow men and women have been so oppressed. Perhaps I was exceptionally morbid, perhaps my ideals were exceptionally high. For high ideals were always being held before me. My grandfather, as you will read, was not only perpetually giving, he was perpetually enjoining upon all others the necessity of giving never-endingly. We were to give not only all our goods, but all our thoughts, all our endeavours; we were to stand aside always to give openings for others. I do not know that I would ask you to look upon life otherwise, or to adopt another standard of conduct, but still it is as well to know beforehand that such a rule of life will expose you to innumerable miseries, to efforts almost superhuman and to innumerable betrayals — or to transactions in which you will consider yourself to have been betrayed. I do not know that I would wish you to be spared any of these unhappinesses. The past generosities of one’s life are the only milestones of that road that one can regret leaving behind. Nothing else matters very much since they alone are one’s achievement. And remember this, that when you are in any doubt, standing between what may appear right and what may appear wrong, though you cannot tell which is wrong and which is right and may well dread the issue — act then upon the lines of your generous emotions even though your generous emotions may at the time appear likely to lead you to disaster. So you may have a life full of regrets which are fitting things for a man to have behind him, but so you will have with you no causes for remorse. Thus at least lived your ancestors and their friends, and, as I knew them, as they impressed themselves upon me, I do not think that one needed or that one needs to-day better men. They had their passions, their extravagancies, their imprudences, their follies. They were sometimes unjust, violent, unthinking.

But they were never cold, they were never mean, they went to shipwreck with high spirits. I could ask nothing better for you if I were inclined to trouble Providence with petitions.

F. M. H.

P. S. — Just a word to make plain the actual nature of this book. It consists of impressions. When some parts of it appeared in serial form a distinguished critic fell foul of one of the stories that I told. My impression was and remains that I heard Thomas Carlyle tell how at Weimar he borrowed an apron from a waiter and served tea to Goethe and Schiller, who were sitting in eighteenth-century court dress beneath a tree. The distinguished critic of a distinguished paper commented upon this story, saying that Carlyle never was in Weimar and that Schiller died when Carlyle was aged five. I did not write to this distinguished critic because I do not like writing to the papers, but I did write to a third party. I said that a few days before that date I had been talking to a Hessian peasant, a veteran of the Avar of 1870. He had fought at Sedan, at Gravelotte, before Paris; and had been one of the troops that marched in under the Arc de Triomphe. In 1910 I asked this veteran of 1870 what the Avar had been all about. He said that the Emperor of Germany having heard that the Emperor Napoleon had invaded England and had taken his mother-in-law Queen Victoria prisoner — that the Emperor of Germany had marched into France to rescue his distinguished connection. In my letter to my critic’s friend I said that if I had related this anecdote, I should not have considered it as a contribution to history, but as material illustrating the state of mind of a Hessian peasant. So with my anecdote about Carlyle. It was intended to show the state of mind of a child of seven brought into contact with a Victorian great figure. When I wrote the anecdote I was perfectly aware that Carlyle never was in Weimar whilst Schiller was alive, or that Schiller and Goethe would not be likely to drink tea and that they would not have worn eighteenth-century court dress at any time when Carlyle was alive. But as a boy I had that pretty and romantic impression, and so I presented it to the world — for what it was worth. So much I communicated to the distinguished critic in question. He was kind enough to reply to my friend, the third party, that whatever I might say he was right and I was wrong. Carlyle was only five when Schiller died; and so on. He proceeded to comment upon my anecdote of the Hessian peasant to this effect: At the time of the Franco-Prussian war there was no emperor of Germany; the Emperor Napoleon never invaded England; he never took Victoria prisoner, and so on. He omitted to mention that there never was and never will be a modern emperor of Germany.

I suppose that this gentleman was doing what is called “pulling my leg,” for it is impossible to imagine that any one, even an English literary critic, or a German Philologist, or a mixture of the two could be so wanting in a sense of humour — or in any sense at all. But there the matter is, and this book is a book of impressions. My impression is that there have been six thousand four hundred and seventy-two books written to give the facts about the Pre-Raphaelite movement. My impression is that I myself have written more than 17,000,000 wearisome and dull words as to the facts about the Pre-Raphaelite movement. These you understand are my impressions; probably there are not more than ninety books dealing with the subject; and I have not myself really written more than 360,000 words on these matters. But what I am trying to get at is that, though there have been many things written about these facts, no one has whole-heartedly and thoroughly attempted to get the atmosphere of these twenty-five years. This book, in short, is full of inaccuracies as to facts, but its accuracy as to impressions is absolute. For the facts, when you have a little time to waste, I should suggest that you go through this book carefully, noting the errors. To the one of you who succeeds in finding the largest number I will cheerfully present a copy of the ninth edition of the Encyclopaedia Britannica, so that you may still further perfect yourself in the hunting out of errors. But if one of you can discover in it any single impression that can be demonstrably proved not sincere on my part, I will draw you a cheque for whatever happens to be my balance at the bank for the next ten succeeding years. This is a handsome offer, but I can afford to make it, for you will not gain a single penny in the transaction. My business in life, in short, is to attempt to discover, and to try to let you see, where we stand. I don’t really deal in facts, I have for facts a most profound contempt. I try to give you what I see to be the spirit of an age, of a town, of a movement. This can not be done with facts. Supposing that when I am walking beside a cornfield, I hear a great rustling, and a hare jumps out; supposing now that I am the owner of that field and I go to my farm-bailiff. I should say “There are about a million hares in that field, I wish you would keep the damned beasts down.” There would not have been a million hares in the field, and hares being soulless beasts cannot be damned, but I should have produced upon that bailiff the impression that I desired. So in this book. It is not always foggy in Bloomsbury; indeed I happen to be writing in Bloomsbury at this moment, and, though it is just before Christmas, the light of day is quite tolerable. Nevertheless, with an effrontery that will I am sure appal the critic of my Hessian peasant story, I say that the Pre-Raphaelite poets carried on their work amidst the glooms of Bloomsbury; and this I think is a true impression. To say that on an average in the last 25 years there have been in Bloomsbury per 365 days, 10 of bright sunshine, 299 of rain, 42 of fog and the remainder compounded of all three would not seriously help the impression. This fact I think you will understand, though I doubt whether my friend the critic will.