Delphi Works of Ford Madox Ford (Illustrated) (68 page)

Read Delphi Works of Ford Madox Ford (Illustrated) Online

Authors: Ford Madox Ford

‘Oh, the poison,’ she said, turning a little pale. ‘I — I lost it. It was stolen. You aren’t angry with me for that?’

‘No, thank God, my darling. But oh, Edith, I was mad enough, vile enough to believe, until almost a minute ago, that you had killed your husband with it. Can you forgive me for

that?

’

She looked at him, with her lips parted in astonishment.

‘You thought I had committed a murder, and

yet

you married me!’ The tears came into her eyes, and she threw her arms round his neck, and, trembling, hid her face. ‘Oh, Clem, how glad I am, how glad I am! I don’t think even

I

love you as well as that. I don’t think I could have married you if I — thought you had committed a murder. Oh, Clem, Clem! How good you are to me. How much you must have loved me!’

The glory faded from the sky as the train rattled forward.

* * *

The Past, with its struggles and heart burnings, was dead — only the good that adversity had brought out in their characters remained.

This was what it had taught them:

‘How you must have loved me!’

THE END

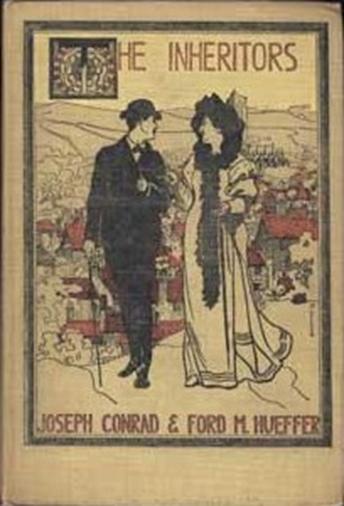

AN EXTRAVAGANT STORY

By Joseph Conrad and Ford Madox Ford

This 1901 part science fiction, part social drama novel was the first of three collaborations between Joseph Conrad and Ford. The novel explores society’s mental evolution and what may be gained and lost in the process of evolving. Written before the First World War, the novel’s themes of corruption and the effect of the 20th Century on British aristocracy appear revolutionary for the time.

The narrative introduces the ‘inheritors’ as a breed of cold materialists, calling themselves Fourth Dimensionists, whose task is to occupy the earth. In the story, an unsuccessful English writer meets a fascinating woman by chance, who seems to talk in metaphors. She claims to be from the Fourth Dimension and a major player in a plan to “inherit the earth”. They go their separate ways with her pledge they will meet again and again.

The first edition

CONTENTS

“Sardanapalus builded seven cities in a day. Let us eat, drink and sleep, for to-morrow we die.”

“Ideas,” she said. “Oh, as for ideas—”

“Well?” I hazarded, “as for ideas — ?”

We went through the old gateway and I cast a glance over my shoulder. The noon sun was shining over the masonry, over the little saints’ effigies, over the little fretted canopies, the grime and the white streaks of bird-dropping.

“There,” I said, pointing toward it, “doesn’t that suggest something to you?”

She made a motion with her head — half negative, half contemptuous.

“But,” I stuttered, “the associations — the ideas — the historical ideas—”

She said nothing.

“You Americans,” I began, but her smile stopped me. It was as if she were amused at the utterances of an old lady shocked by the habits of the daughters of the day. It was the smile of a person who is confident of superseding one fatally.

In conversations of any length one of the parties assumes the superiority — superiority of rank, intellectual or social. In this conversation she, if she did not attain to tacitly acknowledged temperamental superiority, seemed at least to claim it, to have no doubt as to its ultimate according. I was unused to this. I was a talker, proud of my conversational powers.

I had looked at her before; now I cast a sideways, critical glance at her. I came out of my moodiness to wonder what type this was. She had good hair, good eyes, and some charm. Yes. And something besides — a something — a something that was not an attribute of her beauty. The modelling of her face was so perfect and so delicate as to produce an effect of transparency, yet there was no suggestion of frailness; her glance had an extraordinary strength of life. Her hair was fair and gleaming, her cheeks coloured as if a warm light had fallen on them from somewhere. She was familiar till it occurred to you that she was strange.

“Which way are you going?” she asked.

“I am going to walk to Dover,” I answered.

“And I may come with you?”

I looked at her — intent on divining her in that one glance. It was of course impossible. “There will be time for analysis,” I thought.

“The roads are free to all,” I said. “You are not an American?”

She shook her head. No. She was not an Australian either, she came from none of the British colonies.

“You are not English,” I affirmed. “You speak too well.” I was piqued. She did not answer. She smiled again and I grew angry. In the cathedral she had smiled at the verger’s commendation of particularly abominable restorations, and that smile had drawn me toward her, had emboldened me to offer deferential and condemnatory remarks as to the plaster-of-Paris mouldings. You know how one addresses a young lady who is obviously capable of taking care of herself. That was how I had come across her. She had smiled at the gabble of the cathedral guide as he showed the obsessed troop, of which we had formed units, the place of martyrdom of Blessed Thomas, and her smile had had just that quality of superseder’s contempt. It had pleased me then; but, now that she smiled thus past me — it was not quite at me — in the crooked highways of the town, I was irritated. After all, I was somebody; I was not a cathedral verger. I had a fancy for myself in those days — a fancy that solitude and brooding had crystallised into a habit of mind. I was a writer with high — with the highest — ideals. I had withdrawn myself from the world, lived isolated, hidden in the countryside, lived as hermits do, on the hope of one day doing something — of putting greatness on paper. She suddenly fathomed my thoughts: “You write,” she affirmed. I asked how she knew, wondered what she had read of mine — there was so little.

“Are you a popular author?” she asked.

“Alas, no!” I answered. “You must know that.”

“You would like to be?”

“We should all of us like,” I answered; “though it is true some of us protest that we aim for higher things.”

“I see,” she said, musingly. As far as I could tell she was coming to some decision. With an instinctive dislike to any such proceeding as regarded myself, I tried to cut across her unknown thoughts.

“But, really—” I said, “I am quite a commonplace topic. Let us talk about yourself. Where do you come from?”

It occurred to me again that I was intensely unacquainted with her type.

Here was the same smile — as far as I could see, exactly the same smile.

There are fine shades in smiles as in laughs, as in tones of voice. I

seemed unable to hold my tongue.

“Where do you come from?” I asked. “You must belong to one of the new nations. You are a foreigner, I’ll swear, because you have such a fine contempt for us. You irritate me so that you might almost be a Prussian. But it is obvious that you are of a new nation that is beginning to find itself.”

“Oh, we are to inherit the earth, if that is what you mean,” she said.

“The phrase is comprehensive,” I said. I was determined not to give myself away. “Where in the world do you come from?” I repeated. The question, I was quite conscious, would have sufficed, but in the hope, I suppose, of establishing my intellectual superiority, I continued:

“You know, fair play’s a jewel. Now I’m quite willing to give you information as to myself. I have already told you the essentials — you ought to tell me something. It would only be fair play.”

“Why should there be any fair play?” she asked.

“What have you to say against that?” I said. “Do you not number it among your national characteristics?”

“You really wish to know where I come from?”

I expressed light-hearted acquiescence.

“Listen,” she said, and uttered some sounds. I felt a kind of unholy emotion. It had come like a sudden, suddenly hushed, intense gust of wind through a breathless day. “What — what!” I cried.

“I said I inhabit the Fourth Dimension.”

I recovered my equanimity with the thought that I had been visited by some stroke of an obscure and unimportant physical kind.

“I think we must have been climbing the hill too fast for me,” I said, “I have not been very well. I missed what you said.” I was certainly out of breath.

“I said I inhabit the Fourth Dimension,” she repeated with admirable gravity.

“Oh, come,” I expostulated, “this is playing it rather low down. You walk a convalescent out of breath and then propound riddles to him.”

I was recovering my breath, and, with it, my inclination to expand. Instead, I looked at her. I was beginning to understand. It was obvious enough that she was a foreigner in a strange land, in a land that brought out her national characteristics. She must be of some race, perhaps Semitic, perhaps Sclav — of some incomprehensible race. I had never seen a Circassian, and there used to be a tradition that Circassian women were beautiful, were fair-skinned, and so on. What was repelling in her was accounted for by this difference in national point of view. One is, after all, not so very remote from the horse. What one does not understand one shies at — finds sinister, in fact. And she struck me as sinister.

“You won’t tell me who you are?” I said.

“I have done so,” she answered.

“If you expect me to believe that you inhabit a mathematical monstrosity, you are mistaken. You are, really.”

She turned round and pointed at the city.

“Look!” she said.

We had climbed the western hill. Below our feet, beneath a sky that the wind had swept clean of clouds, was the valley; a broad bowl, shallow, filled with the purple of smoke-wreaths. And above the mass of red roofs there soared the golden stonework of the cathedral tower. It was a vision, the last word of a great art. I looked at her. I was moved, and I knew that the glory of it must have moved her.

She was smiling. “Look!” she repeated. I looked.

There was the purple and the red, and the golden tower, the vision, the last word. She said something — uttered some sound.

What had happened? I don’t know. It all looked contemptible. One seemed to see something beyond, something vaster — vaster than cathedrals, vaster than the conception of the gods to whom cathedrals were raised. The tower reeled out of the perpendicular. One saw beyond it, not roofs, or smoke, or hills, but an unrealised, an unrealisable infinity of space.

It was merely momentary. The tower filled its place again and I looked at her.

“What the devil,” I said, hysterically—”what the devil do you play these tricks upon me for?”

“You see,” she answered, “the rudiments of the sense are there.”

“You must excuse me if I fail to understand,” I said, grasping after fragments of dropped dignity. “I am subject to fits of giddiness.” I felt a need for covering a species of nakedness. “Pardon my swearing,” I added; a proof of recovered equanimity.

We resumed the road in silence. I was physically and mentally shaken; and I tried to deceive myself as to the cause. After some time I said:

“You insist then in preserving your — your incognito.”

“Oh, I make no mystery of myself,” she answered.

“You have told me that you come from the Fourth Dimension,” I remarked, ironically.

“I come from the Fourth Dimension,” she said, patiently. She had the air of one in a position of difficulty; of one aware of it and ready to brave it. She had the listlessness of an enlightened person who has to explain, over and over again, to stupid children some rudimentary point of the multiplication table.

She seemed to divine my thoughts, to be aware of their very wording. She even said “yes” at the opening of her next speech.

“Yes,” she said. “It is as if I were to try to explain the new ideas of any age to a person of the age that has gone before.” She paused, seeking a concrete illustration that would touch me. “As if I were explaining to Dr. Johnson the methods and the ultimate vogue of the cockney school of poetry.”

“I understand,” I said, “that you wish me to consider myself as relatively a Choctaw. But what I do not understand is; what bearing that has upon — upon the Fourth Dimension, I think you said?”

“I will explain,” she replied.

“But you must explain as if you were explaining to a Choctaw,” I said, pleasantly, “you must be concise and convincing.”

She answered: “I will.”

She made a long speech of it; I condense. I can’t remember her exact words — there were so many; but she spoke like a book. There was something exquisitely piquant in her choice of words, in her expressionless voice. I seemed to be listening to a phonograph reciting a technical work. There was a touch of the incongruous, of the mad, that appealed to me — the commonplace rolling-down landscape, the straight, white, undulating road that, from the tops of rises, one saw running for miles and miles, straight, straight, and so white. Filtering down through the great blue of the sky came the thrilling of innumerable skylarks. And I was listening to a parody of a scientific work recited by a phonograph.

I heard the nature of the Fourth Dimension — heard that it was an inhabited plane — invisible to our eyes, but omnipresent; heard that I had seen it when Bell Harry had reeled before my eyes. I heard the Dimensionists described: a race clear-sighted, eminently practical, incredible; with no ideals, prejudices, or remorse; with no feeling for art and no reverence for life; free from any ethical tradition; callous to pain, weakness, suffering and death, as if they had been invulnerable and immortal. She did not say that they were immortal, however. “You would — you will — hate us,” she concluded. And I seemed only then to come to myself. The power of her imagination was so great that I fancied myself face to face with the truth. I supposed she had been amusing herself; that she should have tried to frighten me was inadmissible. I don’t pretend that I was completely at my ease, but I said, amiably: “You certainly have succeeded in making these beings hateful.”