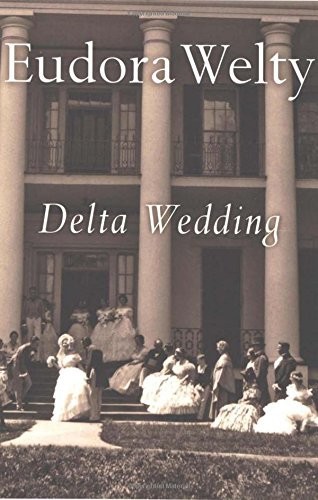

Delta Wedding

Authors: Eudora Welty

Eudora Welty

Table of Contents

A Harvest Book • Harcourt, Inc.

Orlando Austin New York San Diego Toronto London

Copyright 1946, 1945 by Eudora Welty

Copyright renewed 1974, 1973 by Eudora Welty

All rights reserved.

No part of this publication may be reproduced

or transmitted in any form or by any means,

electronic or mechanical, including photocopy, recording,

or any information storage and retrieval system,

without permission in writing

from the publisher.

Requests for permission to make copies of

any part of the work should be mailed to

the following address: Permissions Department,

Harcourt, Inc., 6277 Sea Harbor Drive,

Orlando, Florida 32887-6777.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Welty, Eudora, 1909-2001

Delta wedding; a novel/by Eudora Welty.

p. cm.

ISBN 0-15-124774-9

ISBN 0-15-625280-5 (pb)

I. Title. II. Series.

PS3545.E6D4 1991

813'.52—dc20 90-22030

Printed in the United States of America

EE GG HH FF DD

1To

John Robinson

The nickname of the train was the Yellow Dog. Its real name was the Yazoo-Delta. It was a mixed train. The day was the 10th of September, 1923—afternoon. Laura McRaven, who was nine years old, was on her first journey alone. She was going up from Jackson to visit her mother's people, the Fairchilds, at their plantation named Shellmound, at Fairchilds, Mississippi. When she got there, "Poor Laura little motherless girl," they would all run out and say, for her mother had died in the winter and they had not seen Laura since the funeral. Her father had come as far as Yazoo City with her and put her on the Dog. Her cousin Dabney Fairchild, who was seventeen, was going to be married, but Laura could not be in the wedding for the reason that her mother was dead. Of these facts the one most persistent in Laura's mind was the most intimate one: that her age was nine.

In the passenger car every window was propped open with a stick of kindling wood. A breeze blew through, hot and then cool, fragrant of the woods and yellow flowers and of the train. The yellow butterflies flew in at any window, out at any other, and outdoors one of them could keep up with the train, which then seemed to be racing with a butterfly. Overhead a black lamp in which a circle of flowers had been cut out swung round and round on a chain as the car rocked from side to side, sending down dainty drifts of kerosene smell. The Dog was almost sure to reach Fairchilds before the lamp would be lighted by Mr. Terry Black, the conductor, who had promised her father to watch out for her. Laura had the seat facing the stove, but of course no fire was burning in it now. She sat leaning at the window, the light and the sooty air trying to make her close her eyes. Her ticket to Fairchilds was stuck up in her Madge Evans straw hat, in imitation of the drummer across the aisle. Once the Dog stopped in the open fields and Laura saw the engineer, Mr. Doolittle, go out and pick some specially fine goldenrod there—for whom, she could not know. Then the long September cry rang from the thousand unseen locusts, urgent at the open windows of the train.

Then at one place a white foxy farm dog ran beside the Yellow Dog for a distance just under Laura's window, barking sharply, and then they left him behind, or he turned back. And then, as if a hand reached along the green ridge and all of a sudden pulled down with a sweep, like a scoop in the bin, the hill and every tree in the world and left cotton fields, the Delta began. The drummer with a groan sank into sleep. Mr. Terry Black walked by and took the tickets out of their hats. Laura brought up her saved banana, peeled it down, and bit into it.

Thoughts went out of her head and the landscape filled it. In the Delta, most of the world seemed sky. The clouds were large—larger than horses or houses, larger than boats or churches or gins, larger than anything except the fields the Fairchilds planted. Her nose in the banana skin as in the cup of a lily, she watched the Delta. The land was perfectly flat and level but it shimmered like the wing of a lighted dragonfly. It seemed strummed, as though it were an instrument and something had touched it. Sometimes in the cotton were trees with one, two, or three arms—she could draw better trees than those were. Sometimes like a fuzzy caterpillar looking in the cotton was a winding line of thick green willows and cypresses, and when the train crossed this green, running on a loud iron bridge, down its center like a golden mark on the caterpillar's back would be a bayou.

When the day lengthened, a rosy light lay over the cotton. Laura stretched her arm out the window and let the soot sprinkle it. There went a black mule—in the diamond light of far distance, going into the light, a child drove a black mule home, and all behind, the hidden track through the fields was marked by the lifted fading train of dust. The Delta buzzards, that seemed to wheel as wide and high as the sun, with evening were going down too, settling into far-away violet tree stumps for the night.

In the Delta the sunsets were reddest light. The sun went down lopsided and wide as a rose on a stem in the west, and the west was a milk-white edge, like the foam of the sea. The sky, the field, the little track, and the bayou, over and over—all that had been bright or dark was now one color. From the warm window sill the endless fields glowed like a hearth in firelight, and Laura, looking out, leaning on her elbows with her head between her hands, felt what an arriver in a land feels—that slow hard pounding in the breast.

'Fairchilds, Fairchilds!"

Mr. Terry Black lifted down the suitcase Laura's father had put up in the rack. The Dog ran through an iron bridge over James's Bayou, and past a long twilighted gin, its tin side looking first like a blue lake, and a platform where cotton bales were so close they seemed to lean out to the train. Behind it, dark gold and shadowy, was the river, the Yazoo. They came to the station, the dark-yellow color of goldenrod, and stopped. Through the windows Laura could see five or six cousins at once, all jumping up and down at different moments. Each mane of light hair waved like a holiday banner, so that you could see the Fairchilds everywhere, even with everybody meeting the train and asking Mr. Terry how he had been since the day before. When Mr. Terry set her on the little iron steps, holding her square doll's suitcase (in which her doll Marmion was horizontally suspended), and gave her a spank, she staggered, and was lifted down among flying arms to the earth.

"Kiss Bluet!" The baby was put in her face.

She was kissed and laughed at and her hat would have been snatched away but for the new elastic that pulled it back, and then she was half-carried along like a drunken reveler at a festival, not quite recognizing who anyone was. India hadn't come—"We couldn't find her"—and Dabney hadn't come, she was going to be married. They piled her into the Studebaker, into the little folding seat, with Ranny reaching sections of an orange into her mouth from where he stood behind her. Where were her suitcases? They drove rattling across the Yazoo bridge and whirled through the shady, river-smelling street where the town, Fairchild's Store and all, looked like a row of dark barns, while the boys sang "Abdul the Bulbul Amir" or shouted "Let Bluet drive!" and the baby was handed over Laura's head and stood between Orrin's knees, proudly. Orrin was fourteen—a wonderful driver. They went up and down the street three times, backing into cotton fields to turn around, before they went across the bridge again, homeward.

"That's to Marmion," said Orrin to Laura kindly. He waved at an old track that did not cross the river but followed it, two purple ruts in the strip of wood shadow.

"Marmion's my dolly," she said.

"It's not, it's where I was born," said Orrin.

There was no use in Laura and Orrin talking any more about what anything was. On this side of the river were the gin and compress, the railroad track, the forest-filled cemetery where her mother was buried in the Fairchild lot, the Old Methodist Church with the steamboat bell glinting pink in the light, and Brunswicktown where the Negroes were, smoking now on every doorstep. Then the car traveled in its cloud of dust like a blind being through the fields one after the other, like all one field but Laura knew they had names—the Mound Field, and Moon Field after Moon Lake. When they were as far as the overseer's house, Laura saw all the cousins lean out and spit, and she did too.

"I thought you all liked Mr. Bascom," she said, after they got by.

"It's not Mr. Bascom now, crazy," they said. "Is it, Bluet? Not Mr. Bascom now."

Then the car crossed the little bayou bridge, whose rackety rhythm she remembered, and there was Shellmound.

Facing James's Bayou, back under the planted pecan grove, it was gently glowing in the late summer light, the brightest thing in the evening—the tall, white, wide frame house with a porch all around, its bayed tower on one side, its tinted windows open and its curtains stirring, and even from here plainly to be heard a song coming out of the music room, played on the piano by a stranger to Laura. They curved in at the gate. All the way up the drive the boy cousins with a shout would jump and spill out, and pick up a ball from the ground and throw it, rocketlike. By the carriage block in front of the house Laura was pulled out of the car and held by the hand. Shelley had hold of her—the oldest girl. Laura did not know if she had been in the car with her or not. Shelley had her hair still done up long, parted in the middle, and a ribbon around it low across her brow and knotted behind, like a chariot racer. She wore a fountain pen on a chain now, and had her initials done in runny ink on her tennis shoes, over the ankle bones. Inside the house, the "piece" all at once ended.

"Shelley!" somebody called, imploringly.

"Dabney is an example of madness on earth," said Shelley now, and then she ran off, trailed by Bluet beating plaintively on a drum found in the grass, with a little stick. The boys were scattered like magic. Laura was deserted.

Grass softly touched her legs and her garter rosettes, growing sweet and springy for this was the country. On the narrow little walk along the front of the house, hung over with closing lemon lilies, there was a quieting and vanishing of sound. It was not yet dark. The sky was the color of violets, and the snow-white moon in the sky had not yet begun to shine. Where it hung above the water tank, back of the house, the swallows were circling busy as the spinning of a top. By the flaky front steps a thrush was singing waterlike notes from the sweet-olive tree, which was in flower; it was not too dark to see the breast of the thrush or the little white blooms either. Laura remembered everything, with the fragrance and the song. She looked up the steps through the porch, where there was a wooden scroll on the screen door that her finger knew how to trace, and lifted her eyes to an old fanlight, now reflecting a skyey light as of a past summer, that she had been dared—oh, by Maureen!—to throw a stone through, and had not.

She dropped her suitcase in the grass and ran to the back yard and jumped up with two of the boys on the joggling board. In between Roy and Little Battle she jumped, and the delights of anticipation seemed to shake her up and down.

She remembered (as one remembers first the eyes of a loved person) the old blue water cooler on the back porch—how thirsty she always was here!—among the round and square wooden tables always piled with snap beans, turnip greens, and onions from the day's trip to Greenwood; and while you drank your eyes were on this green place here in the back yard, the joggling board, the neglected greenhouse, Aunt Ellen's guineas in the old buggy, the stable wall elbow-deep in a vine. And in the parlor she knew was a clover-shaped footstool covered with rose velvet where she would sit, and sliding doors to the music room that she could open and shut. In the halls would be the rising smell of girls' fudge cooking, the sound of the phone by the roll-top desk going unanswered. She could remember mostly the dining room, the paintings by Great-Aunt Mashula that was dead, of full-blown yellow roses and a watermelon split to the heart by a jackknife, and every ornamental plate around the rail different because painted by a different aunt at a different time; the big table never quite cleared; the innumerable packs of old, old playing cards. She could remember India's paper dolls coming out flatter from the law books than hers from a shoe box, and smelling as if they were scorched from it. She remembered the Negroes, Bitsy, Roxie, Little Uncle, and Vi'let. She put out her arms like wings and knew in her fingers the thready pattern of red roses in the carpet on the stairs, and she could hear the high-pitched calls and answers going up the stairs and down. She thought of the upstairs hall where it was twilight all the time from the green shadow of an awning, and where an old lopsided baseball lay all summer in a silver dish on the lid of the paper-crammed plantation desk, and how away at either end of the hall was a balcony and the little square butterflies that flew so high were going by, and the June bugs knocking. She remembered the sleeping porches full of late sleepers, some strangers to her always among them when India led her through and showed them to her. She remembered well the cotton lint on ceilings and lampshades, fresh every morning like a present from the fairies, that made Vi'let moan.