Dennis Wheatley - Duke de Richleau 07 (69 page)

Read Dennis Wheatley - Duke de Richleau 07 Online

Authors: The Second Seal

The Colonel gave him a

worried look. “That is only a temporary measure and was brought about by our

inability to foresee the present situation. When we ordered partial

mobilization on the 25th of July there was every indication that the Great

Powers would succeed in preventing the war from spreading. Naturally we wished

to make the conflict with Serbia as brief as possible, so our 2nd army was

included in the partial mobilization and despatched south. As it happened that

was particularly unfortunate, as two of its four corps were stationed in

Bohemia. Not unnaturally, perhaps, learning of our war-like preparations in

Prague and on their own borders, the Russians thought we were mobilizing against

them, so ordered mobilization along our own frontiers themselves. After that it

was found impossible to control events any longer.”

‘So,’ thought the Duke

grimly, ‘von Hötzendorf’s unappeasable hatred of the Serbs had not only been

the major cause of the original outbreak of hostilities, but with a criminal

disregard of consequences, he had ordered military measures, resulting in the

chain of events that had set all Europe ablaze.’ But Colonel Pacher was going

on:

“By the 31st of July,

when Russia ordered general mobilization, it was too late to cancel the

movement of the 2nd Army. With your experience of warfare you will know how

such things work. We couldn’t possibly stop the hundreds of trains full of

troops and equipment halfway to their destinations. To have done so would have

thrown our whole railway system out of gear and created chaos of the movements

of the other Armies. The only thing to do was to let the 2nd Army go on to the

Danube and deploy there; then work out an entirely new time-table for

re-entraining it and bringing it north to the Russian front. But naturally,

that sort of thing takes time, and it will not be ready to start on its

northward journey until the 18th.”

Recalling Sir Henry

Wilson’s statement, that the Russian armies would take several days longer to

mobilize than those of the Dual Monarchy, De Richleau was delighted to think

that von Hötzendorf had already lost his big opportunity and got himself into a

glorious muddle. But he said with suitable gravity:

“That seems most unfortunate.

I imagine sound strategy would have dictated an immediate offensive against the

Russians with everything we could muster while we still had the advantage of

numbers; but now it appears unlikely that we shall be able to bring up our 2nd

Army in time to participate in the first great battle.”

“I fear that is so,” the

Colonel agreed glumly. “But, of course, we are deriving some compensation from

the deployment of the 2nd Army in the south. With his 5th and 6th Armies in

Bosnia, General Potiorek could have menaced Serbia only from the west; whereas

with the deployment of the 2nd Army to the north, he has been able to do so on

two fronts; so the Serbians will be greatly weakened by having to retain forces

along the Danube which might otherwise have been used to resist our offensive

across the Drina.”

“How is it going?”

“It has started well.

Potiorek’s 5th Army began its advance on the 12th and entered Shabatz almost

unopposed. It is now approaching the Jadar. But I am not altogether happy about

our future prospects down there. In my view General Potiorek has deployed his

6th Army too far to the south. Of course, he has to deal with the Montenegrins

on his right flank and take care of a Serbian division that has moved up from

Uzhite; but the trouble is that it is now right out of touch with the 5th. When

the 2nd is withdrawn and the Voyvode Putnik realizes that he has nothing to

fear from that direction, he will be able to oppose our 5th Army with

practically the whole of his forces. As he has ten divisions in northern Serbia

he will outnumber our people, and I fear we may suffer a temporary reverse.”

Having regard to the

relative quality of the troops engaged, De Richleau had no doubt at all that

his new colleague’s pessimism was fully justified. By now his professional

interest was so fully engaged that he had forgotten not only the danger of his

own situation, but its implications; and momentarily found himself thinking as

though he were really an Austrian Staff officer. Instinctively, he said:

“In that case General

Potiorek should be ordered to wheel the bulk of his 6th Army eastward while

there is still time for it to come up alongside the 5th.”

Colonel Pacher took off

his pince-nez and blinked up at him with a shake of the head. “I see you are as

yet unacquainted with one of our major difficulties. After the

C. in C.

, General Potiorek is the foremost

soldier in our army. In addition, through his friend Baron Bolfas, the Emperor’s

A.D.C., he has great influence at Court.”

“I should have thought

his incredibly inefficient arrangements at Sarajevo, having been largely

responsible for the Archduke’s murder, would have cost him that,” put in the

Duke.

“No. He is still in high

favour, and remains a law unto himself. He will not accept advice from us, let alone

orders, and frequently goes over the

C. in C.

’s

head. He is doing so at the moment in a matter that is causing us the gravest

concern. The 2nd Army has the most positive instructions that in no

circumstances is it to cross the Save-Danube line; but he insists that it is

essential to the success of his campaign that it should at least make a

demonstration in force before leaving, and is doing his utmost to secure the

Emperor’s consent to involve it.”

“I see his point of view;

although it is most reprehensible conduct on the part of a junior commander. Of

course, if he succeeds, it may give us a victory in the south. But what of the

north?”

“It has been decided not

to wait for the 2nd Army, and in the course of the next few days we are

launching our first offensive.”

“Do you consider that

really wise?” hazarded the Duke.

“The

C. in C.

is a great believer in the

offensive,” replied Colonel Pacher non-committally. “Our ten cavalry divisions

have already penetrated deep into Russian territory and are meeting with little

opposition.”

De Richleau had already

decided that if he were going to be hanged at all he might as well be hanged

for a sheep as a lamb, and indulge his passion for this fascinating game of war

by learning all he could; so he asked without hesitation:

“In which direction are

we going to strike?”

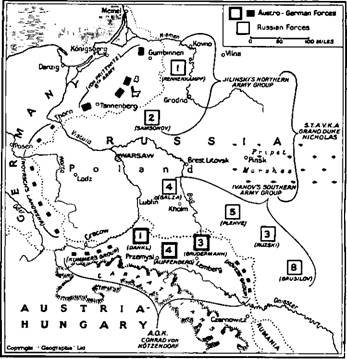

Colonel Pacher stood up

and together they studied the map, which now had a line of pins, varying in

thickness, running in a great ‘S’ bend across its upper half. From Cernowitz,

on the Rumanian border, the line was thin, representing a scratch Command which

had been got together under General K

ö

vess

to cover the upper reaches of the Dniester. It ended a little south of Lemberg,

and from in front of that city up to the right bank of the Vistula, across which

lay Polish soil, the pins were massed solidly, showing the 3rd, 4th and 1st

Armies disposed over a front of a hundred and sixty miles. Then, along the

Vistula and in the neighbourhood of Cracow, the line of pins thinned out again

where General Kummer, with another scratch Command, was covering the frontier

up to the German border. Kummer’s Group lay at right angles to the 1st Army

along the southern frontier of Poland, and from there the huge Polish salient

bellied out westwards. Its arc had pins only at distant intervals to show

German Landwehr units under General von Woyrsch which provided a dubious screen

for Breslau and Posen. Then, north of the Polish salient, from Thorn across

East Prussia to the Baltic, there was a group of flags about the same in number

as those representing one of the three main Austrian Armies. It was labelled ‘8th

German Army: General von Prittwitz’.

Placing a square-tipped

forefinger in the middle of the gap that separated Warsaw, in the centre of the

Polish salient, from the key railway junction of Brest-Litovsk, that lay a

hundred miles behind it, Pacher said:

“We intend to strike due

north, cut off Warsaw, and join up with the Germans advancing south to meet us

from East Prussia.”

“And where are the

Russians?” inquired the Duke, as not a single flag indicating the enemy had yet

been stuck in the map.

“We don’t know for

certain,” the Colonel admitted rather lamely. “We have reason to suppose that

there are four Armies in the Southern Group under General Ivanov, which is

opposed to us, but we have no definite information regarding their whereabouts.”

THE

DEPLOYMENT OF THE ARMIES ON THE EASTERN FRONT

De Richleau endeavoured

to hide his astonishment, and remarked tactfully: “Of course, in the early

stages of a war it is always difficult to locate the enemy’s main

concentrations. But I should have thought it would be incurring a very grave

risk to expose our right flank in such a manner.”

“Our cavalry screen has

met with very little opposition in front of Lemberg, so the

C. in C.

considers it unlikely that the

enemy will be in a position to launch a serious offensive in that direction for

some time. On the other hand, we do know that they have pulled everything out

of the Polish salient to behind the line of the Vistula, so it seems obvious

that they are massing east of Warsaw; and the

C.

in C.

’s

objective is to catch and smash them there before they have a chance to deploy

in line of battle. As they have evacuated the Polish salient, Rummer’s Group

and von Woyrsch’s Landwehr should be able to advance almost unopposed to in

front of Warsaw, and with the Germans coming in from the north we should

succeed in over-running the whole of Poland.”

“But will they?

Apparently they have only one Army in East Prussia. To carry out their share in

this plan effectively they would need to launch practically the whole of it due

south towards Syedlets. That would leave their northern frontier naked. If you

are right in your belief that no great part of the Russian forces are opposite

our southern front, it follows that they must have very large ones up in the

north. I cannot believe that the Germans would be willing to expose East

Prussia, and by denuding it of troops, give the Russians the chance to launch a

major offensive straight on to Berlin.”

The Colonel sighed. “I

very much fear you are right about that. The Germans promised us their

co-operation during peace-time talks, and for the past week the

C. in C.

has been pressing General von

Prittwitz to deploy his 8th Army in the manner agreed; but we have so far got

no satisfaction from him. In fact, last night a telegram came in from Captain

Fleischmann, our liaison officer with the 8th Army, which was most depressing.

It reported that the Russians are entering East Prussia from Kovno and Olita,

and that von Prittwitz is about to strike at them; and that until he has

checked the enemy advance he cannot consider committing any of his troops to a

southward drive into Poland.”

“Yet the

C. in C.

still intends to launch his

offensive almost immediately?”

“Yes. We are hoping that

by the 20th or 21st the Germans may have dealt with the Russian incursion into

East Prussia, and be ready to help us. If not, the direction of our attack will

probably be more to the eastward. But we shall attack all the same. The

C. in C.

is a great believer in the

offensive.”

With that Colonel Pacher

returned to his work and left the Duke to speculate on the information he had

just acquired. Since the Russians had withdrawn all their forces from western

Poland, and the Austrian cavalry was meeting with little opposition further

south, it seemed clear that the Grand Duke Nicholas was acting with commendable

caution. It was estimated that Russia’s initial mobilization in Europe would

put 2,700,000 men in the field, in addition to 900,000 special reserves and

fortress troops. Of this colossal force, mainly consisting of highly trained

regulars, not one thousandth part could yet have been expended. Obviously the

Grand Duke, whom De Richleau knew to be a very capable commander, was holding

them well back, so that the bulk of them could be hurled with equal ease at any

enemy offensive that developed, whether it came from the north, south or

centre. Yet von Hötzendorf, minus his powerful 2nd Army, and now doubtful of

the German co-operation on which he had counted, was still determined to butt

his head into this Russian hornets’ nest.