Dennis Wheatley - Duke de Richleau 07 (88 page)

Read Dennis Wheatley - Duke de Richleau 07 Online

Authors: The Second Seal

:

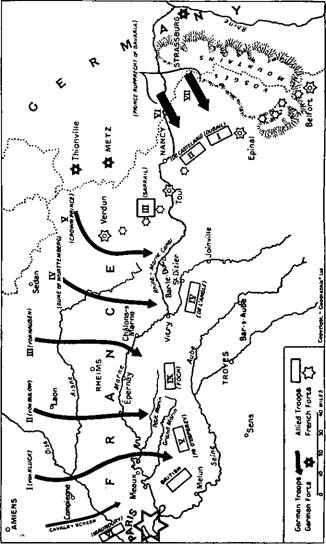

“This ties up with our

intelligence reports. For some days past troop trains have been leaving Belgium

for the East. It is reported, too, that there are no German troops west of the

line Senlis-Paris, so Maunoury’s attack should have a good chance of clearing

the country south of the Marne, and containing the enemy to the north of it.”

“South

of the Marne,” De Richleau said in a puzzled voice. “But little is to be gained

by lopping off the heads of the enemy columns. Surely

north

of the Marne is the right place to strike? It is von

Kluck’s centre and rear at which the blow should be aimed, with the object of

throwing his whole army into confusion and cutting his communications.”

“Ah! But we must act with

some caution,” the Colonel replied. “Maunoury’s Army is of no great strength,

and it would be wrong to ask too much of it. General Joffre has sanctioned this

attack only because his old colleague, General, Galli

é

ni

who is now Military Governor of Paris, pressed him so strongly to agree to it.

He would have much preferred to wait a little until he feels it time to launch

all his Armies in a general counter-offensive.”

Sir Pellinore had been

following the conversation with some difficulty, but he had gathered the gist

of it, and suddenly cut in:

“What’s this? D’you mean

to say that you’re goin’ to let this chance slip? Here you’ve got the Huns

walking sideways-on to you and all you mean to do is to let Maunoury have a

smack at their advance guards. You’re crazy! Plumb crazy! You ought to be

issuing orders now for every man on your entire front to turn and fight.”

De Grandmaison stiffened.

“That,” he said coldly, “is a matter for the Commander-in-Chief. The Armies

that have been fighting for the past fortnight are now near exhaustion. His

view is that we should give them time to recover, and wait until they have been

strongly reinforced before returning to the attack.”

“Reinforced from where?”

asked Sir Pellinore.

“From Verdun. We intend

to give up the fortress, so as to make available for field operations the great

body of men who form its garrison.”

“Give up Verdun!”

De Richleau rose slowly to his feet. He went white to the lips: his grey eyes

were blazing. Suddenly he leaned forward and crashed his fist down on the

table.

“Surrender Verdun!

Shade of St. Louis! I wonder that the ghosts of the Marshals of France do not

rise up and strike you dead! Do the glories of Rocroy, Austerlitz and Jena mean

nothing to you? How dare you even contemplate such a step and still call

yourself a Frenchman!”

The other two had also

risen. Sir Pellinore took the outraged Duke’s arm, and said in English: “Steady

the Buffs! Don’t want this feller forcin’ some stupid duel on you.”

“I’ll meet him and shoot

him any time he wishes,” snarled De Richleau.

De Grandmaison was

trembling with anger, and burst out: “You are protected by your uniform. But I

shall report your disgraceful behaviour to Sir John French. Now, leave my

office before I forget myself.”

As they left the

building. Sir Pellinore said philosophically, “Well, that’s scotched any hope

we had of gettin’ a decent dinner off these fellers. That chap was ‘papa’

Joffre’s blue-eyed boy, you know. Not surprisin’ is it, that with stiff-wallahs

like him about, they’re in such a howlin’ mess?”

“He ought to be shot!” muttered

the Duke savagely. “He ought to be shot! Just think of it! To give up Verdun

and let the Germans through the only part of the line that’s holding!”

“Yes, quite shockin’,” agreed

the Baronet with unusual mildness. “To think, too, that the Germans have

counted their chickens before they are hatched, and that we can’t take

advantage of it. Evidently old von Kluck thinks the Allies are as good as in

the bag already, or he’d never risk marchin’ his crop-heads across the front of

our army. Still, it’s the last round that counts. Sooner or later we’ll knock

the stuffin’ out of the Huns. British Empire is unbeatable.”

It was now six o’clock,

so they decided not to return to Paris until the morning, and set about finding

accommodation for the night. That proved easier than they expected, as General

Joffre appeared to have only his operations staff with him, and apparently did

not bother to keep in close touch with the heads of all the organization

departments necessary to the maintenance and manipulation of a vast army. At a

pleasant inn they got rooms for themselves and their driver, shaved, had a

brush up, and came down to dinner.

But it was a far from

happy meal, as it lay heavily on both their minds that their mission had proved

an utter failure. Colonel de Grandmaison had obviously registered the transfer

of the six German Corps, but only as an interesting piece of information; and

one that made no significant difference to the immediate situation, as he had

no intention of advising his

C. in C.

to engage in a new battle.

Sir Pellinore suggested

that next day they should look in at H.Q., B.E.F. on their way back to Paris,

and, having agreed to start at nine o’clock in the morning, they retired

unhappily to bed.

They were, however,

unable to start at nine, as their driver reported that four hundred miles over

the bad French roads had broken one of the back springs of the Crossley; but he

added that he had been “parleyvooing with a French garage hand who seemed a

sensible cove” and he thought that the car could be ready for the road again by

about one o’clock. In consequence, they had an early lunch in Bar-sur-Aube, and

started soon after one for Melun, where the British G.H.Q. was situated.

The roads were as

congested as on the day before and the car was considerably delayed in getting

through both Troyes and Sens, so it was not until after five that they reached

Melun. General French’s Headquarters were in a pleasant château just outside

the town, and for the travellers it was a tonic to see the good order and

discipline that reigned there.

De Richleau was not the

type of soldier who believed that weary troops should be made to polish buttons

when they might be called on to fight or march again at dawn next morning, but

he did believe that proper pride in routine turn out increased a man’s respect

for himself and his service, and that there was no excuse for anyone at a rear

headquarters to appear ill-shaven or slovenly. Here, both officers and men were

as spick and span as they would have been at Aldershot. On the drive in front

of the house the chauffeurs were whistling as they busily polished the metal

work of the staff cars, and some stocky bow-legged orderlies were walking half

a dozen beautifully groomed horses up and down.

Sir Pellinore’s inquiry

elicited the fact that Sir John French had not yet returned from a day’s tour

of his front line units, and that his Chief of Staff, Sir Archibald Murray, had

just left to visit Sir Douglas Haig at 1st Corps Headquarters. But Sir

Archibald’s deputy was in, and the Duke was delighted when he found this to be

the brilliant strategist he had met at the Carlton Club, General Sir Henry

Wilson.

Sir Henry cocked an

eyebrow when he saw De Richleau dressed as a Brigadier-General, and the Duke,

much embarrassed for once, said quickly that at least he was entitled to the

decorations he was wearing. Sir Pellinore added that they had been “doin’ a bit

of Comic Opera stuff in an attempt to ginger-up the French”; which the tall

Irishman thought a huge joke and, roaring with laughter, took them into the

Mess. As he was providing them both with whisky and soda, Sir Pellinore asked:

“Well! How’s the

contemptible little Army gettin’ along?”

“Oh, not too badly,” replied

the General. “Naturally the men hate retreating, but they’ve given a pretty

good account of themselves. They did all they were asked, and more, in spite of

the fact that they were up against six times their numbers. In the first week

we took a nasty hammering, but the 4th Div. has joined us since, and several

drafts, so on balance I’m inclined to think we’re in even better shape than

when we started.”

“I wish to God that could

be said of the French,” remarked the Duke.

“So do I,” agreed Sir

Henry. “Their best troops showed tremendous

é

lan

,

but the bulk of their Army hasn’t stood up to the Huns as well as we expected.”

“The Admiralty always

told you they wouldn’t,” said Sir Pellinore, unkindly. “Still, it’s not the

men—it’s ‘papa’ Joffre and his Young Turks that are to blame for the mess we’re

in. We’ve just come from G.Q.G. and it has to be seen to be believed. One horse

and a boy. Joffre’s the horse, and they’re both chewin’ the cud in a

pissoir.”

“What had they to say for

themselves?”

“Oh, that the battle is

arranging itself. They’re helping, too. Goin’ to declare Paris an open city and

surrender Verdun.”

The General swung round. “You

can’t mean that?”

“If you don’t believe me,

ask De Richleau. When he heard it, I’d have given anybody ten to one that he’d

either have an apoplectic fit or kill that feller Grandmaison on the spot.”

“Archie Murray was right

then, in his decision this afternoon.”

“If it was to get you

fellers down to Le Havre and back to England, home and beauty in the

Brighton Belle,

he probably was.”

“No. We had Galli

é

ni

here. Just before Messimy was sacked, he made the old boy Governor of Paris. It

was a thundering good appointment, as he has both brains and guts. The trouble

is that, although he was Joffre’s boss when they were in Madagascar together,

he is now in quite a subordinate position to the

C. in C.

, and has only a very limited sphere

of action. His reconnaissances report that there are no Huns at all west of

Paris, and yesterday our aviators confirmed that.”

Sir Pellinore nodded

vigorously. “So they told us at G.Q.G. Von Kluck is wide open. It needs only a

kick in the ribs from Maunoury’s lot to fold up the German flank and land the

whole German right in the devil of a mess.”

“That’s Galli

é

ni’s

view. But ‘papa’ Joffre will give him permission to attack only south of the

Marne, not north of it. So I’m afraid it won’t do much good. He came here to

ask us to join in, and attack von Kluck from the south; but we turned him down.”

“Why?”

“For one thing, because

he hasn’t a shadow of authority to launch a counter-offensive on his own. For

another, because, now that we are in better shape, Sir John wrote to Joffre the

day before yesterday offering to stand and fight again. But G.Q.G. replied that

they thought it better not to for the time being. We can’t afford to be left

with our right wing in the air; so we must continue to conform to the general

retirement.”

“Do you realize, though,”

put in the Duke, “that, not only is von Kluck’s flank open, but he has nothing

behind him? The two German Corps allocated to invest Namur, which should now be

following him up, have been sent to the East Prussian front. And four others

with them.”

Sir Henry gave him a

sharp glance. “Are you certain of that? What leads you to suppose so?”

De Richleau told his

story as briefly as possible. The General showed a sudden excitement and, when

he had done, asked:

“Does Galli

é

ni

know this?”

“Not as far as I know. We

told de Grandmaison at G.Q.G., but he didn’t seem to think it could make much

difference now.”