Desert Queen (29 page)

Authors: Janet Wallach

Tags: #Adventure, #Travel, #Non-Fiction, #Biography, #History

The Turkish Government, riddled with corruption and bribery, was in dire financial straits. It had borrowed money to fight the Balkan Wars and depended upon loans from European countries to survive. The Germans had been particularly helpful, financing and constructing the important railway line from Berlin to Baghdad. But the aggressive German presence in the Middle East was threatening the British, who had always been concerned with protecting their routes to India.

Now Britain’s interest in the region had become even greater. Its unrivaled navy delivered goods around the world and brought home three quarters of England’s food supply. To maintain its superiority, in 1911 the First Lord of the Admiralty, Winston Churchill, had ordered a major change, switching the nation’s battleships from coal-burning engines to oil. Far superior to the traditional ships, these new oil-burning vessels could travel faster, cover a greater range, and be refueled at sea; what’s more, their crews would not be exhausted by having to refuel, and would require less manpower.

Britain had been the world’s leading provider of coal, but she had no oil of her own. In 1912 Churchill signed an agreement for a major share in the Anglo-Persian Oil Company, with its oil wells in southern Persia and refineries at Abadan, close to Basrah. It was essential for Britain to protect that vital area, yet with the Ottoman Empire so weakened, the region was highly vulnerable, particularly susceptible to German-sponsored attack.

Gertrude was eager to report her findings on the desert Arabs to the British Ambassador in Constantinople. Despite British hopes that, should war break out, the Turks would remain neutral, suspicions were rife that Turkey might ally itself with Germany. She had seen with her own eyes how loose the Ottoman rule had become over the Arab tribes, and she believed that the British could take advantage of the situation. Well-informed friends had convinced her that the Arabs in Syria were favorably disposed to British rule. She had heard, too, that in Arabia, the increasingly powerful Ibn Saud, who had spent his years in exile in Kuwait, an area friendly to the British, was eager to ally himself with England.

Sir Louis Mallet listened carefully. Intrigued by her story, he immediately wired Sir Edward Grey, the Foreign Secretary. He described her trip, her impressions of Ibn Rashid, what she had heard about Ibn Saud, and the limp rule of the Turks. There was not a shadow of authority, he noted; “the tribes under Ottoman rule were out of hand. Miss Bell’s journey, which is in all respects a most remarkable exploit, has naturally excited the greatest interest here.”

Rumors of Gertrude’s adventures quickly spread around town, and acquaintances from earlier trips were eager to hear her tales. Her stay in Constantinople was brief, but she dined at the home of Philip Graves, a

Times

correspondent (his wife agape as Gertrude puffed away on a cigarette), and saw the newly married young diplomat Harold Nicolson and his pregnant wife, Vita Sackville-West.

But socializing was not Gertrude’s desire, and on May 24, 1914, she was back in London, recipient of the prestigious gold medal from the Royal Geographical Society. Returning to Rounton, she sought only tranquillity, recuperating from the emotional and physical exhaustion of her trip. Yet in England, too, she found that life was in a state of flux: society was changing. During her absence, controversial books had been published: Proust had written

Swann’s Way

, D. H. Lawrence had brought out

Sons and Lovers

and James Joyce produced

Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man

; George Bernard Shaw’s boisterous play

Pygmalion

had opened at His Majesty’s Theatre in April 1914, with its shocking line “Not bloody likely” parroted across the nation. The Suffragists were still battling, but women had already been released from the bondage of whalebone and steel and were enjoying the freedom of elasticized brassieres. On a more somber note, the world was on the edge of turmoil, only two months away from war.

W

hile Gertrude rested at home, shattering news arrived in England: the heir to the Austro-Hungarian throne, Archduke Ferdinand, had been assassinated. The murder had taken place on June 28, 1914, in the Serbian capital of Sarajevo; the assassin, a Bosnian sympathetic to the Serbs’ demand for independence. The incident, that “damned fool thing in the Balkans,” was just the kind of spark that the German Chancellor Otto von Bismarck had predicted would inflame the world in war. The stunning event touched off a series of pacts and alliances that had been signed by the leaders of the major European nations.

The Anglo-French Entente of 1904 had allied England and France against the aggressive nation of Germany. It followed on the heels of the Anglo-Russian Convention of 1907, uniting England and Russia, two governments that were highly suspicious of each other but even more fearful of the Germans. And it wasn’t just paranoia that made England, France and Russia sign a Triple Entente. War was “a biological necessity,” proclaimed General Friedrich von Bernhardi, one of the leading German military thinkers. Germany now had the second most powerful navy in the world (Great Britain still had the first), and German businessmen and politicians licked their lips at the prospect of bigger markets, expanded territory and the possibility, as they saw it, of becoming the world’s greatest power. The British, the French and the Russians all feared that war-hungry Germans would march across the Continent, both to the east and to the west, on their way to conquer the world.

The assassination of the Austro-Hungarian archduke brought an immediate reaction. Austria-Hungary, hoping to annex Serbia as she had annexed Bosnia and Herzegovina, declared war on Serbia. But Russia, which considered itself a Slavic nation, expressed outrage at the idea that the Slavic Serbs would be swept up into the Austro-Hungarian Empire. The Russian declaration of war touched off a German promise to come to the aid of Austria-Hungary. German mobilization, German forces pressing against the borders of France, and a German fleet prepared to enter the English Channel produced an angry response: France and England had no choice but to activate their forces and join together in the war against the Germans. By August 1, 1914, guns and cannons boomed across the Continent.

On the Eastern Front, the Turks soon allied themselves with the Germans. The British Government was particularly concerned with protecting both its precious routes to India and its petroleum fields in the Persian Gulf, now susceptible to enemy aggression. Gertrude, once the bane of British officials, became a source of vital information about the East. She was asked for a full report on what she had learned in Syria, Iraq and Arabia, and on September 5, 1914, she sent her assessment to the director of Military Operations in Cairo, who immediately passed it on to Foreign Secretary Sir Edward Grey:

Syria [she wrote], especially Southern Syria, where Egyptian prosperity is better known, is exceedingly pro-English. I was told last winter by a very clever German named Loytved, an old friend of mine now at Haifa, that it would be impossible to exaggerate the genuine desire of Syria to come under jurisdiction. And I believe it.…

On the whole I should say that Iraq would not willingly see Turkey at war with us and would take no active part in it. But out there, the Turks would probably turn their attention to Arab chiefs who had received our protection. Such action would be extremely unpopular with the Arab Unionists who look on Sayid Talib of Basrah, [the sheikh of] Kuweit, and Ibn Saud, as powerful protagonists. Sayid Talib is a rogue, he has had no help from us, but our people (merchants) have maintained excellent terms with him. Kuweit depends for his life on our help and he knows it. Ibn Saud is most anxious to get some definite recognition from us and would be easy to secure as an ally. I think we could make it pretty hot for the Turks in the Gulf.

Her report was studied with deliberation at both the War Office and the Foreign Office in London and at Military Intelligence in Cairo. In Europe the battles were already raging; in another few weeks, Britain, France and Russia would be at war against the Turks. Now, in September 1914, even before the men who ran the government had decided on their policy toward the Ottomans, Gertrude presented them with a strong recommendation to organize the Arabs in a revolt against the Turks. She wanted desperately to be on the scene in the East. But for more than a year she was refused permission; the area was considered too dangerous for a female. Being a woman was a major obstacle.

Gertrude Bell, aged three, just after the death of her mother in 1871.

(University of Newcastle)

Gertrude, aged eight, reading to her bored brother, Maurice.

(University of Newcastle)

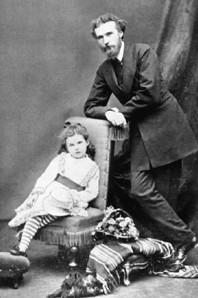

Gertrude, aged four, with her adored father, Hugh Bell. “Obstacles are made to be overcome,” he often told her.

(University of Newcastle)

Gertrude, aged nine, and her brother, Maurice, with their stepmother, Florence Bell.

(University of Newcastle)