Design for Murder

DESIGN FOR MURDER

The first Wednesday in July seemed like winter, it was so cold and depressingly wet.

When I drove back from Cheltenham through the Cots

wold countryside, heavy grey clouds were sagging down to fill

every hollow of the hills with clammy mist. Wishing that I’d

worn something warmer, I switched on the car radio and listened resentfully to a transatlantic report about the heat wave that was engulfing the U.S.A.

I reached the by-road for Steeple Haslop, and turned and

dipped downhill through the beechwoods into the village. The

wide main street, flanked on one side by the river, was rainswept and deserted. Yet the scattered cottages and early-Saxon

church, all built of locally-quarried limestone which had

mellowed over the centuries, still managed to exude a warm

and friendly charm.

At Millpond Lane I was tempted to make the short diver

sion and stop off at my own cottage to change my clothes, but

I was already later than I’d planned to be. As I turned in at

the wrought-iron gates of Haslop Hall just up the hill beyond

the village, the newscaster gave a time check. Twelve-fifteen,

and I’d told Oliver to expect me at about eleven-thirty at our

studio-cum-office-cum-workshop that adjoined his flat above

the old Coach House. I’d been doing various things in Chel

tenham, chief of which was selecting fabric samples for the

Design Studio’s latest commission—a complete new decor for

Mrs. Cynthia Fairford’s drawing room at Dodford Old Rec

tory.

The long driveway curved through sheep-grazed parkland

towards the ancient manor house, now half-obscured by drift

ing mist so that it was merely a looming grey outline. At the fork, I swung right and continued along a narrower, laurel-lined drive to the stable block. I drove through the archway beneath the clocktower into the paved courtyard, and when I

switched off the engine the country quiet was accentuated by

the hiss and drip of rain. But then I heard a scurry of movement. Not, it seemed to me, of a horse stomping restlessly in

its stall, but of hasty human footsteps.

Or was that only what I afterwards imagined it to have

been?

As usual, I entered through the glazed door at the side of

the Coach House which led by way of a boxed-in staircase

directly up to the workshop. The door at the head of the

stairs stood ajar, and as my eyes came level with the studio

floor I saw, lying there, a huddled dark shape silhouetted

against the light from the window. I bounded up the last few stairs. Then I stopped short, frozen with horror.

Oliver was lying between the desk and the table, on his

side, with arms and legs splayed out. The longish black hair

at the back of his head was bloody, and an oozing stain was spreading on the mushroom-coloured carpet. Fighting an im

pulse to shrink away, I crouched down and put out my hand

to touch his cheek. Though it was still warm, the skin felt life

less, and I knew with a terrible certainty that Oliver was

dead.

A yard from his head, near the cabinet in which we stored

rolled-up drawings, lay a heavy bronze statuette ten inches

high that usually stood on top of the bookshelves

...

it was

an African fertility-god with its grotesquely outsize phallus

which Oliver delighted in keeping on full view, largely, I suspected, to upset his father.

Instinctively I reached out and picked up the statuette.

Then it occurred to me that I shouldn’t be touching what was

obviously the murder weapon and hastily dropped it. At the

same moment I heard footsteps outside. The downstairs door opened and someone started to come up.

It was Tim Baxter, and I realized I was very glad to see

him.

“Oh, hallo Tracy,” he began. “I just wanted to ...” Tim

broke off as his gaze dropped to the body on the floor. “Good

God, what’s happened?”

I shook my head helplessly, unable to speak. Tim went

down on one knee and felt Oliver’s pulse ... needlessly.

“He’s dead! What happened?” asked Tim a second time,

rising to his feet.

“I

...

I just walked in a minute ago and found him ...

like this.”

Tim gave me a hard, steady stare, looking as if he won

dered whether or not to believe me. Then his expression

relaxed a bit.

“It can’t have happened long ago,” he said. “He’s still

warm.”

“I know.”

“You’ve touched him?”

I nodded. “I wasn’t sure if he really was dead.”

“Did you touch anything else?” Tim’s glance went to the

bronze statuette.

“Yes, I did pick up the statuette,” I admitted. “But then I

realised that I shouldn’t have done and I dropped it again.”

“Too right you shouldn’t have picked it up. With your

fingerprints all over it, you’d have a hell of a lot of explaining

to do.” He drew out his handkerchief and reached for the stat

uette. He gave it a good wipe, careful not to touch the

bloodied end, then he replaced it on the carpet.

“There, that’s safer,” he said. “Now we’d better call the police.”

“Safer for whom?” I burst out before I could stop myself. It had suddenly occurred to me that perhaps Tim Baxter was

taking this chance, using this excuse, to wipe his

own

finger

prints

off the murder weapon.

I watched Tim’s brown eyes flare as he realised what I was

thinking. To cover up, I said quickly, “Don’t you see, you

might have wiped the murderer’s fingerprints off too.”

Tim pressed his lips together, his expression thoughtful. “I doubt he’d have been so careless as to leave any.”

“I might have disturbed him, though,” I pointed out. “I thought I heard footsteps when I arrived.”

Tim had picked up the phone, but he paused and gave me a sharp look.

“Any idea who it was? Did you get a glimpse of him?”

I shook my head. “I’m not even certain that I did hear anybody.”

But I

was

fairly certain. Could it have been Tim? If so, it

was clever of him to return to the scene immediately after my arrival. It would explain his presence in the neighbourhood of

the Coach House if anyone else had chanced to see him, and it would account for any other fingerprints of his that might be found in the studio.

He said, “Was it a burglar, do you think, whom Oliver sur

prised? Is anything missing, Tracy?”

I glanced around the room. Everything appeared to be in

its usual place, with no sign that a search had been made. The

hexagonal desk was untidy, but that was quite normal; Oliver

always managed to create chaos when he opened the morning’s mail. There was a catalogue beside the telephone, a roll of Sellotape, a selection of coloured ball-points, and ...

“It doesn’t look like it,” I said. “Not that there was any

thing much to steal in here—nothing particularly valuable, I

mean. And Oliver never carried a great deal of money on

him. He preferred to use his credit cards.”

“He’s still wearing his wristwatch, I see, and a signet ring.”

Tim was fiddling with some of the loose papers on the desk,

and I said uneasily, “You shouldn’t move anything, you

know. The police will expect to find things exactly as they

were.”

I’d left myself wide open to a comeback from Tim about

me

having picked up the statuette, but he just nodded and dropped the sheet of paper he was holding. Then he dialled

999.

“Oliver’s father will have to be told,” I said.

“Shall I go?”

“No, I’ll do it.” I didn’t care for the thought of being left

here on my own with the body. “I’ll go now, before the police arrive.”

I slipped out while Tim was talking into the phone. Once through the courtyard archway I turned left along an avenue

of horse chestnut trees, which a month ago had looked

magnificent with their creamy white blossom but today

dripped forlornly in the rain. Then out into the open across

neat lawns and well-tended rosebeds towards the house.

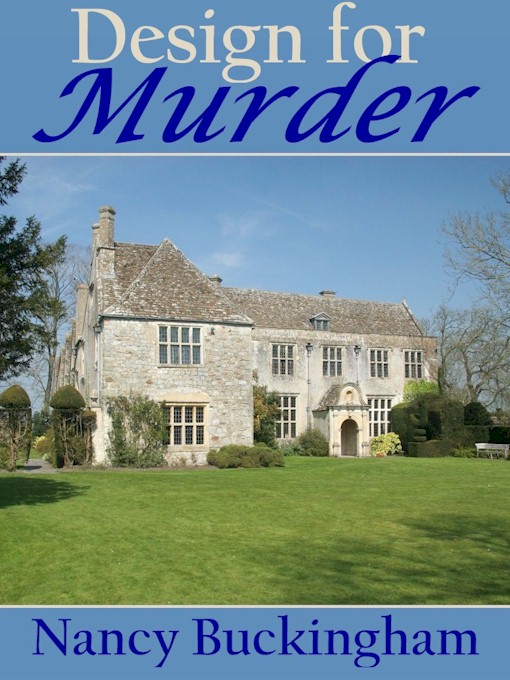

Originally built in the fifteenth century, Haslop Hall had been added to over the centuries before architecture became an exact science. It was a happy hotchpotch of pitched roofs

and pointed gables, of leaning chimneys and mullioned win

dows eccentrically positioned. It was listed as a landmark

building, as it well deserved to be.

I entered beneath the Gothic-arched portal and tugged the

iron bell handle. After quite a wait my summons was an

swered by Grainger. He and his wife ran the domestic side of Haslop Hall, with the aid of a couple of daily women, one of

whom doubled for Oliver in his flat.

“Miss Yorke. Good afternoon.”

“Is Sir Robert at home, please?”

“I think not, miss. I believe that the master is still out

around the estate somewhere. But if you will take a seat, I

will enquire. Or Lady Medway, perhaps, if she is now re

turned from riding?”

It wouldn’t be right for me to break this dreadful news via Oliver’s stepmother, his father’s glamorous third wife. “No, it

must be Sir Robert himself. There’s been an accident, you

see. I mean

...”

Grainger gave me a startled look from beneath his bushy eyebrows. He was a short, thickset man, and stood with his arms hanging, palms forward, which gave him an almost

apelike appearance.

“An accident, miss? To Mr. Oliver?”

“Please,” I begged, “try to find Sir Robert for me. He must

be told immediately.”

I waited impatiently in the Great Hall, not sitting down but pacing around beneath the gilt-framed portraits of the family

ancestors, which Oliver, to annoy his father, insisted on

calling the Rogues’ Gallery. It was nearly five minutes before

a door leading from the rear regions opened and a tall,

stooped figure came through.

Sir Robert Medway, though nudging sixty, was still a hand

some man, but problems with his heart had marked him,

leaving him a shade too spare of flesh. An unhealthy pallor showed from under his summer tan. He came to me, his walk

ing stick hooked over an arm, still wearing a dripping rain

coat and muddy Wellingtons, careless of the mess he was mak

ing on the priceless Bakharan carpet.

“Miss Yorke, what is this I hear from Grainger? How badly is Oliver hurt? Where is he?”

I felt terribly nervous, wondering how he would take the news. He and Oliver had been at loggerheads for years, but

even so Oliver was his son and heir, and it would be a terrible

shock.

“I’m dreadfully sorry, Sir Robert, but I’m afraid that Oliver

is

...

dead.”

“Dead?” A tremor shook his body. “What happened, girl? Tell me!”

“I don’t really know what happened, Sir Robert. I’ve been in Cheltenham all morning, and I arrived at the studio just a few minutes ago and found Oliver lying on the floor. He’d been hit on the head.” Better to get it over with in one go.

“There seems no doubt, I’m afraid, that he was murdered.”

“Murdered? Oh, my God! Are the police there? Is that

what they say?”

“No. We’ve called the police, of course, but they haven’t arrived yet. There hasn’t been time.”

“We?” he asked sharply.

“Tim Baxter happened to come by

...

just after me. He’s

waiting there with Oliver.”

Sir Robert’s agony showed in the look he turned on me. Usually so self-assured and confident, he seemed lost now.

“Hadn’t we better get over there?” I suggested gently.

“Yes ... yes, you’re right.” With a visible effort he pulled

himself upright and marched towards the outer door.

Grainger suddenly appeared from nowhere and I guessed that

he’d been eavesdropping.

“Sir Robert, what am I to tell her ladyship when she arrives

back?” he enquired anxiously.

Sir Robert’s stick fell to the floor, and Grainger dived to re

trieve it. “Tell Lady Medway nothing. I’ll be back as soon as

I can.”

Sir Robert was already through the front door and heading

across the lawn towards the chestnut avenue, taking such long

loping strides with the aid of his stick that I had to trot to

keep up with him. It was raining again, and the slashing

raindrops struck through my cotton blouse and made me

shiver.