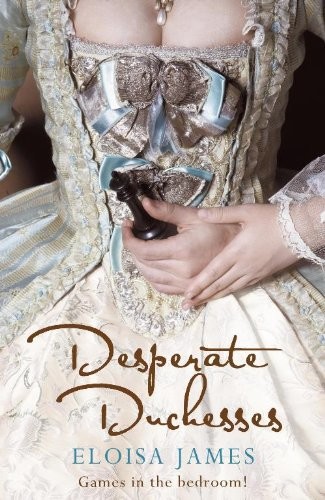

Desperate Duchesses

Read Desperate Duchesses Online

Authors: Eloisa James

Tags: #Fiction, #Romance, #Historical, #General

ELOISA JAMES

Desperate Duchess

This book is dedicated to my father, Robert Bly, winner of the American Book Award for Poetry. There were times in my

adolescence when he embarrassed me by the fierceness of his love and the sheer exuberance of his joy for life. That is the

extent of any resemblance between the poetic marquess of this book and my father, whose poetry—and brains—far

exceeds that of the writer I depict here.

So my second dedication is to the poet Christopher Smart (1722–1771), who unknowingly offered up his poetry to be

sacrificed in the name of fiction. As with any quotation pulled from its context, Mr. Smart’s poetry appears here to be far

more unintelligible than it truly is. In particular, “For My Cat Jeoffrey” is a cheerfully exuberant love poem to a cat; in Mr.

Smart’s honor I am putting the entire poem on my website. Visit

www.eloisajames.com

and enjoy Jeoffrey in his full

splendor.

Contents

A Prelude

Knowing precisely why no one wants to marry you is…

“In Paris, a married lady must have a lover or…

Roberta entered the room just as the peacock tail sprang…

“A duchess!” Whatever Roberta had been expecting in the way…

Harriet, Duchess of Berrow, hadn’t been in London for a…

Roberta would be the first to admit that life with…

“An intimate family supper,” Jemma said with obvious satisfaction. “How…

From the Duchess of Beaumont to the Duke of Vil iers:

The last person Jemma expected to welcome into her bedchamber…

There hadn’t been such excitement over a bal since Princess…

Jemma had to acknowledge that if her husband was beautiful,…

The news spread throughout the bal room within a few minutes.

It wasn’t until nearly morning that Roberta was able to…

Final y the bal had dwindled to the point at which…

Early the next afternoon, Beaumont House was brimming like a…

“I told you that the kitten wanted to come,” Teddy said.

When Jemma took a bath, she invariably thought about chess.

Elijah woke the next morning as the very first light…

The Duke of Vil iers spent the morning at Parsloe’s. He…

Roberta greeted the news that her father had just arrived…

Elijah came home after the cloth makers and before the…

Roberta felt as if she’d fal en through a hole in…

The invitations were delivered by footmen.

Charlotte could tel before she put her slipper from the…

Damon was wel aware that he was consumed by lust.

Charlotte found herself seated at the right hand of her…

The Duke of Vil iers had made up his mind. While…

The windows in the smal back bal room were open to…

Jemma was a trifle irritated. She and Vil iers played a…

In the end, they settled in a smal sitting room,…

He had spread out the huge silk skirts of her…

Vil iers stood quietly in the doorway, one eyebrow raised.

What happened to you? Where did you go?” Damon demanded.

Roberta woke up alone.

Roberta stretched, feeling a pleasurable ache in al parts of…

The two boats carrying Jemma and Vil iers and the marquess…

He was free, obviously a reason for rejoicing. The moment…

From Damon Reeve, Earl of Gryffyn, to the Duke of…

It was a noise beside her bed that woke her…

Dawn was curling over Wimbledon Commons, making the wheels of…

They returned for breakfast to find the house ful of…

“I think,” Roberta said, “you might have let me win…

A Note About Chess, Politics and Duchesses

About the Author

Praise

Other Books by Elosia James

Copyright

About the Publisher

A Prelude

November 1780

Estate of the Marquess of Wharton and Malmesbury

K

nowing precisely why no one wants to marry you is slim consolation for the truth of it. In Lady Roberta St. Giles’s case, the evidence was al too clear—as was her lack of suitors.

The cartoon reproduced in

Rambler’s Magazine

depicted Lady Roberta with a hunched back and a single brow across her bulging forehead. Her father knelt beside her, imploring passersby to find him a respectable spouse for his daughter.

At least that part was true. Her father had fal en to his knees in the streets of Bath, precisely as depicted. To Roberta’s mind, the

Rambler’s

label of

Mad Marquess

had a certain accuracy about it as wel .

“Inbreeding,” her father had said, when she flourished the magazine at him. “They assume your physique is affected by the sort of inbreeding that produces these characteristics. Interesting! After al , you could have been dangerously mad, for example, or—”

“But Papa,” she wailed, “couldn’t you make them print a retraction? I am not misshapen. Who would wish to marry me now?”

“Why, Sweetpea, you are entirely lovely,” he said, knitting his brow. “I shal write a paean on your beauty and publish it in

Rambler’s

. I wil explain precisely why I was so distraught, and include a commentary about the practices of hardened rakehel s!”

Rambler’s Magazine

printed the marquess’s 818 lines of reproving verse, describing the nefarious gal ant who had kissed Roberta in public without so much as a by-your-leave. They resurrected the offensive print as wel . Buried somewhere in the marquess’s raging stanzas describing the peril of walking Bath’s streets was a description of his daughter: “Tel the blythe Graces as they bound, luxuriant in the buxom round, that they’re not more elegantly free, than Roberta, only daughter of a Marquess!” In vain did Roberta point out that “elegantly free” said little of the condition of her back, and that “buxom round”

made her sound rather plump.

“It implies al that needs to be said,” the marquess said serenely. “Every man of sense wil immediately ascertain that you have a charmingly luxurious figure, elegant features and a good dowry, not to mention your expectations from me. I cleverly pointed to your inheritance, do you see?”

Al Roberta could see was a line declaring that her dowry was a peach tree.

“That’s for the rhyme,” her father had said, looking a bit cross now. “Dowry doesn’t rhyme with many words, so I had to rhyme dowry and peach tree. The tree is obviously a synecdoche.”

When Roberta looked blank, he added impatiently, “A figure of speech in which something smal stands for the whole.

The whole is the estate of Wharton and Malmesbury, and you know perfectly wel that we have at least eleven peach trees. My nephew wil inherit the estate, but the orchards are unentailed and wil go to you.”

Perhaps there were clever men who deduced from the marquess’s poem that his daughter had eleven peach trees and a slender figure, but not a single one of those men turned up in Wiltshire to ascertain for himself. The fact that the original cartoon remained on display in the windows of Humphrey’s Print Shop for many months may also have been a consideration.

But since the marquess refused to undertake another trip to the city wherein his daughter was accosted—“You’l thank me for that later,” he added, rather obscurely—Lady Roberta St. Giles found herself heading quickly toward that undesirable stage of life known as “old maid.”

Two years passed. Every few months Roberta’s future would pass before her eyes, a life spent copying and cataloging her father’s poems, when not alphabetizing rejection letters from publishers for use by the marquess’s future biographers, and she would rebel. In vain did she reason, implore or cry. Even threatening to burn every poem in the house had no effect; it wasn’t until she snatched a copy of “For the Custards Mary Brought Me” and threw it in the fire that her father understood her seriousness.

And only by withholding the single remaining copy of the Custard poem did she gain permission to attend the New Year’s bal being held by Lady Cholmondelay.

“We’l have to stay overnight,” her father said, his lower lip jutting out with disapproval.

“We’l go by ourselves,” Roberta said. “Without Mrs. Grope.”

“Without Mrs. Grope!” He opened his mouth to bel ow, but—

“Papa, you do want me to have some attention, don’t you? Mrs. Grope wil cast me entirely in the shade.”

“Humph.”

“I shal need a new dress.”

“An excel ent thought. I was in the vil age the other day and one of Mrs. Parthnel ’s children was running about the square looking blue with cold. I’ve no doubt but that she could use your custom.”

She barely opened her mouth before he lifted his hand. “You wouldn’t want a gown from some other mantuamaker, dearest. You’re not thinking of poor Mrs. Parthnel and her eight children.”

“I am thinking,” Roberta said, “of Mrs. Parthnel ’s bungled bodices.”

But her father frowned at that, since he had strong views about the shal ow nature of fashion and even stronger views about supporting the vil agers, no matter how inferior their products.

Unfortunately, the New Year’s bal produced no suitors.

Papa could not forbear from bringing Mrs. Grope—“’Twil hurt her feelings too much, my dear”—and consequently, Roberta spent the evening watching revelers titter at the presence of a notorious strumpet amongst them. No one appeared to be interested in whether the Mad Marquess’s daughter had a humped back or not; they were too busy peering at the Mad Marquess’s courtesan. Their hostess was incensed at her father’s rudeness in bringing his

chère-amie

to her bal , and wasted none of her precious time introducing Roberta to young men.

Her father danced with Mrs. Grope; Roberta sat at the side of the room and watched. Mrs. Grope’s hair was adorned with ribbons, feathers, flowers, jewels and a bird made from papier-mâché. This made it easy for Roberta to pretend that she didn’t know her own parent; when the said plumage headed in her direction, Roberta would slip away for a brisk strol . She visited the ladies’ retiring room so many times that the company likely thought she had a female complaint to match her invisible hump.

Around eleven o’clock, a gentleman final y asked her to dance. But he turned out to be Lady Cholmondelay’s curate, and he immediately launched into a confused lecture to do with notorious strumpets. He seemed to be equating Mrs. Grope to Mary Magdalene, but the dance kept separating them before Roberta could grasp the connection.

Unfortunately, they came face-to-face with the marquess and Mrs. Grope just when the curate was detailing his feelings about trol ops.

“I take your meaning, sirrah, and Mrs. Grope is no trol op!” the marquess snapped. Roberta’s heart sank and she tried vainly to turn her partner in the opposite direction.