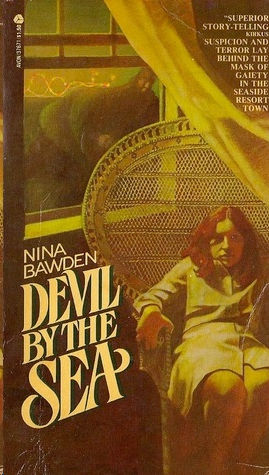

Devil By The Sea

Authors: Nina Bawden

MODERN CLASSICS

433

Nina Bawden

Nina Bawden, CBE, is one of Britain’s most distinguished and best-loved novelists, both for adults and children

(Peppermint Pig

and

Carrie’s War

being among her most famous books for young people). She has published over forty novels and an autobiography,

In My Own Time.

She was shortlisted for the Man Booker Prize for

Circles of Deceit

and her novel

Family Money

was filmed by Channel 4, starring Claire Bloom and June Whitfield. In 2004 she received the S. T. Dupont Golden Pen Award

for a Lifetime’s Contribution to Literature. She lives in London.

Who Calls the Tune

The Odd Flamingo

Change Here for Babylon

The Solitary Child

Just Like a Lady

In Honour Bound

Tortoise by Candlelight

Under the Skin

A Little Love, A Little Learning

A Woman of My Age

The Grain of Truth

The Birds on the Trees

Anna Apparent

George Beneath a Paper Moon

Afternoon of a Good Woman

Familiar Passions

Walking Naked

The Ice House

Circles of Deceit

Family Money

A Nice Change

Ruffian on the Stair

Dear Austen

Published by Hachette Digital

ISBN: 978-0-748-12746-7

All characters and events in this publication, other than those clearly in the public domain, are fictitious and any resemblance to real persons, living or dead, is purely coincidental.

Copyright © Nina Bawden 1976

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, without the prior permission in writing of the publisher.

Hachette Digital

Little, Brown Book Group

100 Victoria Embankment

London, EC4Y 0DY

For

A.S.K. and T.R.F.

Chapter One

The first time the children saw the Devil, he was sitting next to them in the second row of deckchairs in the bandstand. He

was biting his nails.

On the roof, the coloured flags cracked and streamed in the cold breeze from the sea but in the sheltered well of the bandstand

it was warm and windless, the sun held the last heat of summer. Sleepy flies droned heavily over the sand scuffed on the flagstones

by the children’s feet. From time to time the blue sky split as an American jet plane screamed low.

The audience, this September afternoon, was made up of the very young, and the very old. The children, bright as butterflies

in their summer dresses, filled the front rows of chairs; the old people huddled in rugs and scarves at the back, beyond the

aisle. The local pensioners were issued with cheap season tickets by the council: wringing their last advantage from a mean

world, they filled their seats at every performance.

Looking at the man sitting next to them, the children thought he must be old too, or sick. He wore a full-skirted naval bridge

coat and a blue woollen muffler knotted round his neck. Beneath his cloth cap his face was thin, the cheeks so hollow that

his mouth stuck forwards like a dog’s mouth.

Grinning, Hilary nudged Peregrine with her elbow. She aped the man, tearing at the sides of her fingers with her teeth, rolling

her eyes like a mad person. Peregrine watched

her uncomfortably and then, as her acting grew wilder, he was seized by a fearful joy and laughed aloud.

The man turned and looked at them. A shadow crossed his face: like an animal, he seemed to shrink and cringe before the mockery

Hilary had made of him. She stopped biting her nails and moved her hand nervously up her cheek and across her hair, pretending

she had been brushing something from her face. He continued to watch her with a steady, careful stare. She fumbled in the

pocket of her cotton dress. Her voice croaked with embarrassment.

“Would you like a toffee?”

The man looked beyond her, to Peregrine. Briefly, their eyes met. Peregrine could not look away, he was transfixed. The man’s

eyes were dark and dull, dead eyes without any shine in them. They reflected nothing.

The man stirred and coughed. His thin cheeks filled out and the spit sprayed from his mouth. “You’re a nice little girl,”

he said, and smiled. It was a gentle smile, quite at odds with his appearance. He took a toffee with long, sharp fingers and

popped it quickly in his mouth as if he were afraid it would be taken from him.

Hilary said, “Are you hungry? It must be awful to be hungry.”

She was aware that it had been unkind to make fun of him. He could not help being sick and ugly. Normally, she did not suffer

unduly for her bad behaviour towards other people unless she was punished for it. Her imagination was almost entirely absorbed

by her own feelings which were, on occasion, bitter and terrible, and by the wild, dramatic happenings of her private world.

But now her conscience was aroused by the man’s sad and derelict air. Her heart swelled with pity.

“You can have them all if you’re hungry. I don’t want them.” She thrust the crumpled bag of sweets on to the man’s

lap. His narrow, yellow face bent towards her. Reluctantly she looked up at the muddy eyes that showed nothing, neither hope

nor despair nor love nor hate.

The man clicked his tongue against his teeth. “Are you sure you don’t want them?”

She shook her head and lied, “I don’t like toffees.”

“What about your little brother?” Peregrine had withdrawn himself to another chair further along the row. He disliked embarrassing

situations.

“They make his teeth wobble. He’s just seven and all his teeth are falling out.”

The man edged his chair closer to Hilary’s. He smelt of wet mackintoshes like the cloakroom at school. Slowly his nervous

tongue crept out of his mouth and slithered along his lips.

Hilary hunched herself small in her deckchair and watched the stage. Uncle Jack, the Kiddies’ Friend, was making a bunch of

flowers grow in an empty can. There was only one more trick after the can and then they would have the Children’s Talent Competition.

It was always held on a special day, the last day of the season. The Fun Fair would remain open for a little longer but after

to-morrow there would be no more shows on the pier, the deckchairs would be hidden under their tarpaulin covers, the summer

would be over.

The summer I was nine, thought Hilary. It will never come again. Next summer I shall be ten and then eleven and soon I shall

be old. Soon, I shall die.

The man was leaning closer still. His smell was in her nose and throat. She felt his hand stroking her knee and squirmed away.

His fingers felt cold and hard like a chicken’s foot. Ashamed, she stared at the stage, trying not to cry, pretending she

hadn’t noticed what he was doing.

Uncle Jack came to the front of the stage and smiled at the children, his perpetual, shining smile. He had stiff, curly

hair like a doll. His teeth shone and his hair shone and he wore a great ring with a winking stone on the little finger of

his left hand.

“Now, children, this is what you’ve been waiting for, isn’t it? What? I can’t hear you.”

“Yes,”

bellowed the children with scarlet faces and straining lungs.

“That’s better.

That’s

better.” He held up his hand for silence. “Those of you who have tickets, come up on to the stage. Gently, now. Don’t all

rush at once. You might knock me over.”

There was a roar of laughter. A little girl sitting in front of Hilary stood up and skipped in front of her mother’s chair.

The woman creaked forward to pick up her canvas beach-bag, enormous, sun-reddened shoulders bulging out of her dress. She

took out a green ticket.

“Here you are, Poppet. Now remember, stand up nice and straight and smile…”

Poppet took the ticket. Over her mother’s shoulder she smiled triumphantly at Hilary. She was very beautiful. She had fair,

polished hair that bobbed on the shoulders of her green, satin dress. Her eyes were wide and blue like china; beneath her

short skirt her long, brown legs looked like a miniature chorus-girl’s. The man took his hand away from Hilary’s knee. His

teeth tore at his nails again.

Poppet jumped up on to the front of the stage. Her skirt flew up showing white frilly knickers with lace round the legs. Hilary

saw them enviously. Her own knickers were voluminous, made of the same stuff as her dress and fastened with tight elastic.

Slowly, like the tide, the children flowed on to the stage. Some of them were shy: if they were little, Uncle Jack patted

them on the head, if they were big he shook hands with them in a jolly, comradely way.

Hilary sighed. Screwing round in her chair, she looked for her half-sister, Janet. She saw her, standing by the entrance to

the bandstand and talking to Uncle Aubrey. Waving her hands about in an affected way, she was quite preoccupied with her conversation.

Her back was to the stage.

Hilary felt her heart pump inside her like an engine. She turned to her brother and said, “I’m going in the competition, too.”

Blithely, he refused to believe her. “You haven’t got a ticket.”

She scowled. “I shall say I’ve lost it.”

“That’s wicked,” he accused her. “It’s a lie. God doesn’t like us to tell lies.”

Hilary saw the limpid light of Heaven shining from his eyes and hesitated. Peregrine was good: his goodness was as unquestioned

as the rising sun. She knew him to be her spiritual superior and herself to be hateful and base.

She wriggled her shoulders and flung at him, “Mind your own business.” She stood up and walked towards the stage, appalled

by her own behaviour. Her legs seemed to be moving independently like someone else’s legs. She could feel eyes sticking into

her like hot spikes.

She stood in front of the stage and looked up at Uncle Jack. He saw a stout, pale-skinned child with red hair. Her nose was

short and thick, her mouth was small and obstinate. Her plainness was redeemed by a bright, intelligent look which could be

hidden at will beneath an expression of extreme stupidity. Uncle Jack held out his hand to her. “Come on, little lady, don’t

be frightened.” His hand, soft and damp-skinned, grabbed at hers.

She said, prissy-mouthed, “I haven’t got my ticket. I did have one, though. My sister bought it for me. I put it in the pocket

of my frock but it fell out.”

Uncle Jack stopped smiling and suddenly looked quite different, mean and wary. He looked much older when you were close to

him, she decided. There was a faint-smear of what looked like face cream on the wrinkles at the corners of his eyes. He hesitated

and pursed his lips.

“All right,” he said, turning away, “go and join the others.”

Hilary was bowed down with humiliation. She caught her lower lip between her teeth and blinked back her tears. From the stage,

the bandstand looked enormous, row upon row of green and white striped deckchairs filled with pale, staring faces.

The accompanist struck a chord on the piano and the first child walked up to the microphone. He was very little, a tiny boy

in crimson velvet trousers, and Uncle Jack had to shorten the stand as far as it would go. The boy wore glasses and his face

was round and dark as a plum. His voice was gruff. His song began, “I’m too small to be in the infantry,” and ended, “But

I’m in the Lord’s Armee.”