Dialogue (20 page)

Authors: Gloria Kempton

Scenario: A man and woman are intent on scamming an elderly woman (or man) in the parking lot of a bank. Using the victim's point of view, write a one-page scene of dialogue for each Enneagram number, using the following focus:

#1 - begins to lecture the couple about the moral value of scamming people in parking lots #2 - wants to help, eager to be scammed (not knowing she is)

#3 - begins to instruct the couple on a better approach for their scam, one that would be more successful

#4 - makes a scene, screaming for security

#5 - watches and listens and waits and wonders while the scammers persuasively chatter away

#6 - is suspicious and skeptical; asks lots of questions of the scammers about their approach

#7 - puts a positive spin on the encounter or pretends it's not happening

#8 - takes over the situation or gives the couple a lecture about what they should be

doing with their lives

n

H

#9 - doesn't want any trouble; is kind and can't say no

*

o

S

S

[ there is a place — using dialogue to reveal story setting and background ]

Of all of the elements of fiction, setting has always been the most difficult for me to incorporate into my stories because, while I'm an observer of human nature, I forget to notice my environment. I take walks with a certain friend on occasion and she is forever stopping because she hears the chattering of a flicker (what's that?) and wants to interact with it. Or she might pass a certain tree or bush and stop to touch it. Without her by my side, I notice none of these things.

What I do love is to listen to people talk. To eavesdrop. Dialogue is my favorite element of telling stories. When I learned—I can't remember how— that I could use dialogue to reveal setting in my stories, I was thrilled. No more long narrative descriptions where I was trying to describe things I never "saw" in the first place. All I had to do from now on in the way of setting was notice what my characters noticed. That was easy enough because the characters I was used to creating weren't all that different from myself.

This may not be your problem. You may love to describe your story's setting and can easily go on for pages doing so. But that's a problem of another kind. Unless you're writing literary fiction, pages of description aren't usually what a reader is looking for, and he will often skip over it. It depends on the kind of story you're writing, of course. Literary and mainstream fiction are sometimes setting driven, but in the other genres, setting is most often simply the story's background. And dialogue is a useful tool for revealing it.

In order to reveal it through dialogue, of course, you have to first know your characters.

know your characters

Just as we want our characters to speak authentically out of who they are, we also want our settings to be authentic, so that when we plunk our stories down somewhere we can bring our readers in and know that all of our props and background characters are for real. The very first thing we can do to ensure that this happens is to know our characters. It's only when we know our characters and how they feel and relate to the settings in which they find themselves that we can create authenticity in a scene. We have to know them so well that when we create dialogue for them that's connected with their setting, we're not surprised at how they feel about where they are.

For example, if your character, John, finds himself in the middle of a crowded street fair on a blind date and he's claustrophobic, he isn't going to take his time at a booth admiring the leather belts. You might want to mention the leather belts, though, to show that John is a biker. This is your story setting, and you have an opportunity here. Rather than let the need to establish setting drive the scene, go for authenticity and let John's claustrophobic, biker self drive the scene through dialogue.

"Yeah, cool belts," John said, nodding at the owner of the booth and nudging Lori along. "I only have ten belts now." An older man bumped into him and John swore. "It's sure hot, isn't it?" He pulled his kerchief out of his back pocket and tied it around his head. "I bet it's twenty degrees hotter in this crowd than it is out there." He looked longingly through the crowd to the empty sidewalk a few feet away.

You get the idea. You want to weave the setting details into the dialogue, integrating action and narrative. You're looking for a three-dimensional feel.

It's important to know your character. Would a character who lives in Seattle even notice the Space Needle on his way to work in the morning? I live in Seattle, and I can tell you that I see it sometimes because it stands by itself and it's so tall, but most of the time I don't really

see

it. Oh, except on New Year's Eve and the Fourth of July when fireworks are shooting out the top of it—then everyone in Seattle notices it, if they're outside.

When you're on vacation, how often do you and your family and friends sit around and have a lively discussion about the hotel room you've rented for the weekend?

When at work, do you and your co-workers have regular animated discussions about your office building, the color of the walls, the way the desks are arranged, the drab carpet, etc.?

When taking your kids or grandkids to the park, are your eyes on the elm trees or your kids? On the ducks in the pond or your grandkids? If you were to strike up a conversation with a stranger, also with kids, would you most likely talk about the playground equipment or your kids?

You can see where this is going. Getting setting details into a scene is a little tricky because people/characters don't sit around discussing place.

However, setting isn't just about concrete place details. Setting isn't just a house or a beauty salon or a park. Setting can be an industry, a profession, or an organization. Whether or not your characters are sitting around discussing place, there are many opportunities to get setting details into scenes of dialogue if you are fully confident of your setting and you know your character.

Let's go back to John for a moment. You want to give the dialogue scene a three-dimensional feeling, so you have John saying,

"Wow, look at these cool garden decorations. Oh, and hey, here's a booth with homemade kitchen towels."

John the biker? I don't think so. I hate to stereotype any group of people, but if this biker is into garden decorations and homemade kitchen towels, you better set this up before we get to the street fair so we'll believe you. And there better be a good reason, too.

No, John is more likely to say,

"Hey, babe, there's the beer garden,"

grab his old lady's hand and pass right by all of the booths full of garden decorations and homemade kitchen towels.

Know your character so you'll know what he might notice at a street fair, a circus, or the grocery store. Know what he might notice and what he might say about what he notices. What he would notice and not say anything about. Know him very well so your dialogue scenes will ring true, which is always more important than anything else.

establishing setting

A written story is like a movie, where we see the characters on a screen acting out their scenes. As writers, we don't want our readers to have to work hard at

seeing

our characters, at visualizing the setting where the characters are in dialogue with each other. This means we need to make sure to establish the setting in the beginning of each scene of dialogue. If you open a scene with dialogue, integrate some setting details as quickly as you can so the reader can begin to picture the characters and the atmosphere in which the dialogue takes place. This is one way to make the scene three-dimensional so your characters aren't talking to each other in a vacuum.

Use only those details that will further the story situation, your theme, or your character's conflict. Once the setting is established for the dialogue, you can relax a bit, but continue to feed setting details into the scene so the reader can continue to visualize where the characters are in relation to their physical surroundings.

too much too soon

When writing dialogue, there's something we can keep in mind that will help us immensely. The story's dialogue shouldn't be that different from real-life conversation. With that in mind, when was the last time you or another person engaged in conversation that focused on setting to the exclusion of just about anything else?

"Oh and here we are at the circus. Just smell that popcorn, would you, and well, my favorite is the cotton candy, but I can't wait to see the clowns. As a child, they were my favorite part, and the sawdust on the ground feels so crunchy."

"I know what you mean. Here come the elephants with their pretty riders in pink outfits matching the elephants' neck ruffles. Don't you love how the trapeze artists are always in such good shape? They must work out for hours every day."

"Okay, I'm counting eleven clowns that have climbed out of that Volkswagen now. How do they do that?"

In case you haven't noticed, this isn't working. The author (that would be me, hate to say it) is trying to acclimate us to the setting by throwing all kinds of setting details into the dialogue. While dialogue is a great way to introduce the setting, it's not effective to dump it all on the reader at once. The above is called an "info dump," and it never works. It's contrived and unnatural, not the way people really talk. So let's say you want to give the reader the authentic feeling of being at the circus, but in a natural way, weaving it into the dialogue. Everything depends on the story situation you're developing in the scene. No matter what your agenda as the author, you can't let

your

agenda drive a scene. The characters' needs should always drive the scene. So, let's say a married couple on the verge of divorce has arrived at the circus for one last date together with their four-year-old son. Let's use the mother's first-person voice. The action is your primary focus, but you want the setting to feel authentic. You

dont

want an info dump.

"Cotton candy, Mom?" Jason turned to me, his eyes wide with wonder at everything around him.

"Sure, honey." She stepped up to the cotton candy man and gave him two dollars. "One, thanks."

"I want one, too." Aaron looked at me, and I remembered how much he loved cotton candy.

The sawdust crunched under our footsteps as we made our way to the auditorium. "Remember when circuses were under a tent?" Aaron said as he led the way past the cages of tigers and lions.

He said that every time we'd gone to a circus for the last ten years.

A clown on stilts passed us, smiling down at Jason and stopping to shake his hand.

"Tall man, Mom," he said.

I'd never understood why he directed all of his comments to me rather than Aaron. Was it because Aaron seldom interacted with his son?

I think it's clear why this circus scene works better than the previous one. The setting details in the first scene feel contrived, like the author's goal is to make sure the setting comes through. In the second scene, the setting is the scene's backdrop and the details are integrated into the story situation. It feels much more natural this way.

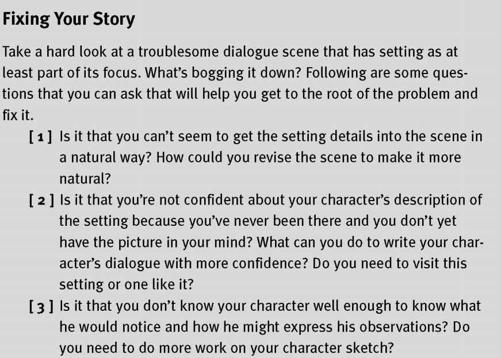

There's nothing wrong with wanting to get the details into a scene as soon as possible. This is good because when characters start talking, the reader needs to know where to picture them.