Diary of a Stage Mother's Daughter: A Memoir (21 page)

Read Diary of a Stage Mother's Daughter: A Memoir Online

Authors: Melissa Francis

Tags: #Biography & Autobiography, #Personal Memoirs, #Entertainment & Performing Arts

BOOK: Diary of a Stage Mother's Daughter: A Memoir

6.26Mb size Format: txt, pdf, ePub

Photo by: NBCU Photo Bank

Fake snow falling indoors on the studio set in Culver City, on the magical day my Brownie troop came to visit the show. On the show, it was Christmas Day, and the Ingallses couldn’t get to the barn to get their gifts because they were snowed in by the blizzard.

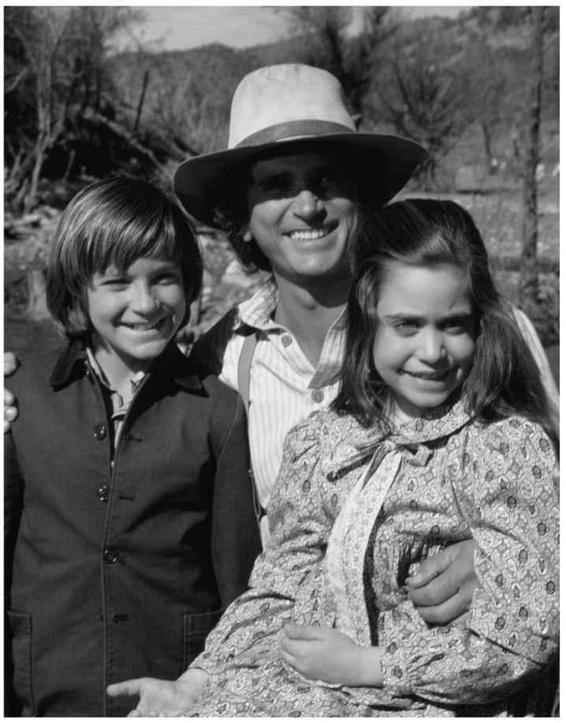

Photo by: NBCU Photo Bank

The scene where Michael Landon (as Charles Ingalls) stopped the train and climbed aboard after deciding to adopt Jason Bateman (as my brother James) and I, rather than sending us off to an orphanage. We were rehearsing, so I hadn’t turned on the tears, yet.

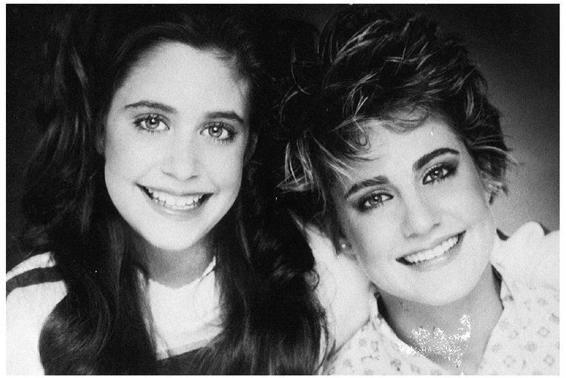

Photo by: NBCU Photo Bank

A glamour shot of me and Tiffany right after I started at Chaminade. That’s my cheerleading uniform. Tiffany’s spiky hairdo covered the scars on her forehead from the accident.

Photo courtesy of the author

Taken just before I left for Stanford summer school; the torn jeans were my new uniform of choice.

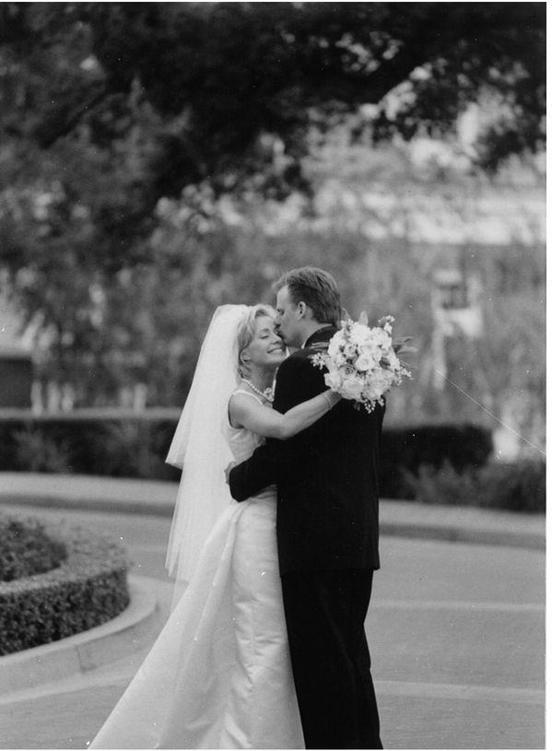

Photo courtesy of the author

Marrying Wray, in 1999 at Sherwood Country Club.

Photo courtesy of the author

“You realize you’re paying for that car, right?” Tiffany said to me when she came into my room and saw the brochure.

I just raised my eyebrows and shrugged. I’d realized by now that Mom was controlling every dime that came in. She collected everything my father, Tiffany, or I made and doled it out as if it were hers. I’d seen her write checks out of the account that was supposed to be my trust fund.

“Isn’t that account for college?” I’d asked when I saw my name at the top of the check. She paused initially, like she’d been caught with her hand in the cookie jar, but then explained that she was writing a check for my private school tution.

“It’s for your education. You don’t want to pay for Chaminade? That’s not your bill? That’s mine? How about your clothes? Your horses? Your head shots? Your hair appointments? All mine? I don’t have furs or big diamonds! I barely have clothes! You wear designer everything! What a spoiled monster you are!”

She’d attack with such vehemence anyone who dared to probe into how she was handling the money that each of us soon gave up. It was exhausting.

The irony was that, now that I was emancipated, anything I made was supposed to be my own. Those checks no longer had to go into a “trust.” But gaining control of my money never seemed like a real possibility to me.

Still, I began to worry that Mom saw herself as the family banker, and she didn’t seem like much of a long-term investor, or even fiscally responsible.

I tried to talk to Dad about it the next time we were alone.

“You certainly don’t have to have a BMW,” he said. “You could be sensible and buy yourself a gently used Honda. That’s what I would do. I think that car you’re buying is silly and a waste of money.”

The severity of his tone panicked me. Was there reason to worry? Was money running out? In my most adult voice I said, “I’d like to know how much money I have left.”

Dad put down the paper he’d been reading and said, “Look, college will be paid for, no matter what. Everything that comes in is spent on you and Tiffany. You should have quit riding horses earlier if you were worried about saving money. You should get a good used car. Don’t blame your mom for decisions you’re making. You wanted us to spend family money on clothes and horses and private schools and save your own earnings off to the side? Well, I guess that would nice. If you had spent less that could have happened. Everyone’s spending has gotten way out of control, and you don’t make the same bread you used to. I mean, that’s fine. You don’t need to work. Other kids aren’t out there earning money like you. You just need to understand the math.”

I got his logic. And I couldn’t disagree. I just would have liked to have been informed when we officially started spending what I had thought was my trust fund for later. Had I known the money I was making wasn’t just going into a pot somewhere, waiting until I turned eighteen, I might have made different decisions.

That assertion made me seem pretty selfish. I would have spent differently the last few years if I knew I was spending the money

I

was making? Now I felt guilty on top of everything else.

I

was making? Now I felt guilty on top of everything else.

When the red BMW arrived from the factory, Mom brought it to school with a huge red bow on the roof and parked it in the faculty parking lot. I immediately got detention for leaving my car in the faculty lot, even though the principal, Brother Bill, knew I’d had nothing to do with it. He had to punish someone for the obnoxious behavior and he didn’t have jurisdiction over Mom. I’m not sure anyone did.

In a single move, Mom pissed off my teachers and alienated my friends, all to show off. Then she wanted a debt of gratitude from me for giving me such a great birthday gift. I spent the next few days doing damage control at school.

“I really got in a lot of trouble over the car,” I grumbled after dinner one night.

She laughed in disbelief. “You’re so ungrateful! I bought you a beautiful red BMW convertible for your birthday! Name one other parent you know who did that!”

It wasn’t worth pointing out that most parents wouldn’t handle all of our finances the way she was. She would just hit me and ground me, and never cede the point anyway.

We were in the kitchen. I was washing the dishes, having made chicken and rice for the two of us. Dad was still at his office, hiding from the rancor that had taken over the house lately. Mom was standing at the tile island in the middle of the room sorting bills and reading the junk mail.

“I know. It’s just that we aren’t allowed to park in the faculty lot.” That was hardly the issue and we both knew it.

She shrugged. “They are all just jealous because it’s such a nice car. You don’t have to have nice things if you don’t want to.”

“Even still, I’m not sure hitting them over the head with it is the way to go.”

“Great.” She sighed and threw the junk mail in the trash. “If that’s how you feel, I’ll drive the car tomorrow. You can ride to school with Cori.”

The only way I had of escaping my mom was to get out of the house. Once I had a car, I’d use any excuse to go out. There was always a price to pay once I got home—she would be suspicious of my whereabouts, or irritated by my increasing independence, or both—but evading her grasp for an afternoon or evening was worth it.

I joined the track team, which annoyed Mom to no end. I’d never been allowed to participate in a team sport because the practices would place time demands on my schedule. Mom always said there was nothing special about being part of a team. But by high school, I wanted to be part of a group, not always an individual. Track wasn’t exactly a team sport the way basketball was, but by this point, all of my classmates had laid claim to various sports and track was the only sports team I could join this late in life and do decently.

I loved having a uniform and going to meets. I could run relatively fast and placed well in the hurdles, and I somehow showed promise at the field events, like javelin and triple jump. Plus track was a positive way to shape up or lose weight without starving. But Mom hated that someone other than her was managing my time.

One day after a track meet I walked into the house with a medal I’d won. Even though we’d come in second, I was proud that the coach had let me run with the 440-yard relay team. My hands shook before the race, but I ran my heart out, and I still glowed with the feeling of winning a ribbon with three other girls at my side.

Other books

Caress of Fire by Martha Hix

Forever Yours by Daniel Glattauer, Jamie Bulloch

I Love My Healed Heart: 4 Book Box Set/Omnibus (Erotic Romance) by Lacey, Sabrina

The Secret Friend by Chris Mooney

The Bloodline Cipher by Stephen Cole

Fuego mágico by Ed Greenwood

The Good, the Bad and the Wild by Heidi Rice

River: A Novel by Lewis, Erin

Seconds by Sylvia Taekema

The Alpine Betrayal by Mary Daheim