Dickinson's Misery (16 page)

Read Dickinson's Misery Online

Authors: Virginia; Jackson

Yet as history would have it, not until seven years later, after her death, did Niles and Roberts Brothers publish in what Austin Warren would later call “slim grey volumes” the verse that Higginson would so emphatically characterize as “something produced absolutely without the thought of publication, and solely by way of expression of the writer's own mind” (

Poems

1890, iii).

29

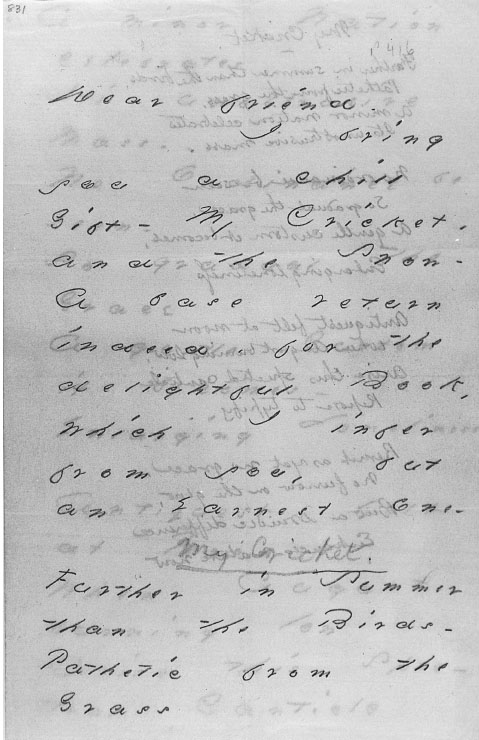

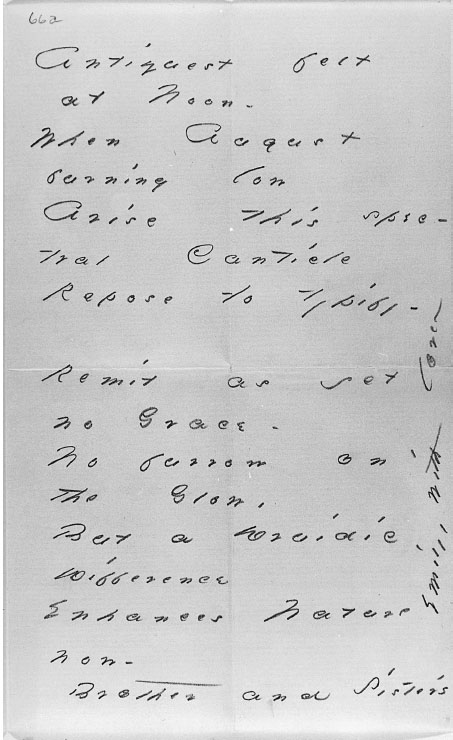

Whatever Dickinson's own intentions may have been, the fact that Niles chose not to publish her poems until they could be circulated as if not intended for public circulation increased their commodity value beyond anyone's expectations. The practical editor of that first edition, Mabel Loomis Todd, transformed Dickinson's reference to her lines into a penciled title, and lineated the poem directly on the manuscript (

fig. 15a

). Whatever genre we might assign to Dickinson's lines during the years they were exchanged between Dickinson and various individuals, they became lyrics in 1890. The maze of particular practical-social relations to which they pointed before they were published as lyrics became a much more abstract and simplified social relation after publication determined their genre.

Figure 15a. Emily Dickinson to Thomas Niles, 1883. Todd's transcript of lines, which she copied onto the verso of the first sheet of the letter, is visible in the photograph above; Todd also penciled in the later title. Courtesy of Amherst College Archives and Special Collections (ED mss. 831, 831a, 831b).

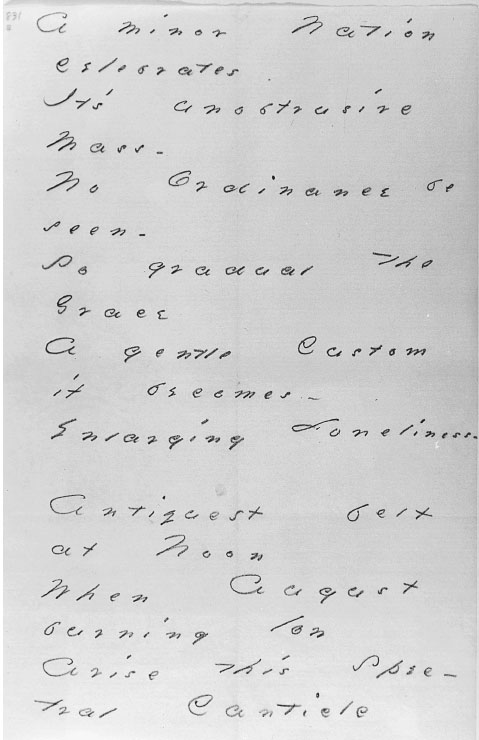

Figure 15b. Emily Dickinson to Thomas Niles, 1883. Courtesy of Amherst College Archives and Special Collections (ED mss. 831, 831a, 831b).

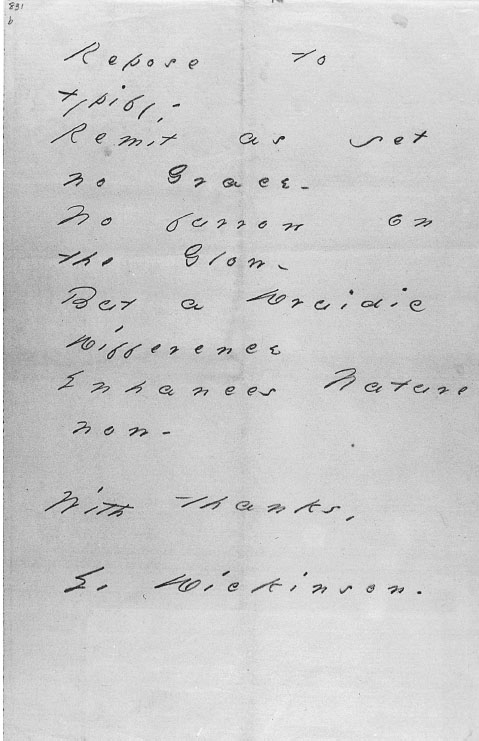

Figure 15c. Emily Dickinson to Thomas Niles, 1883. Courtesy of Amherst College Archives and Special Collections (ED mss. 831, 831a, 831b).

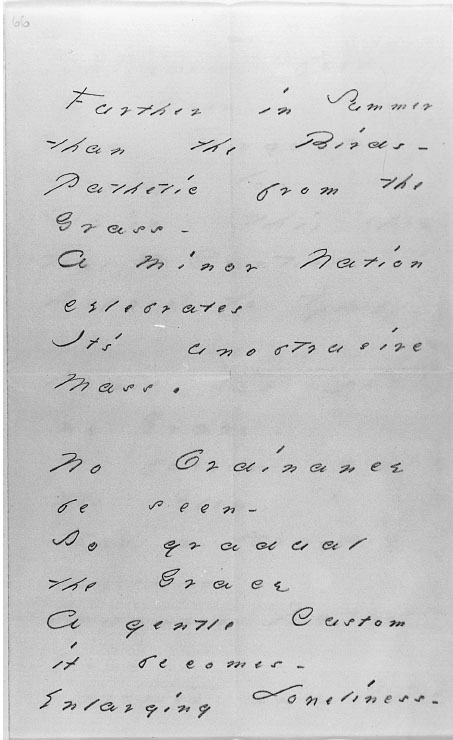

Before that happened, however, Dickinson sent the lines that she had sent to Vanderbilt and Higginson and Niles to one other person. Although Dickinson could not have known it in 1883, the woman to whom she addressed this last manuscript (

figs. 16a

,

16b

), Mabel Loomis Todd, would become the first and in many ways most influential hands-on editor of Dickinson's poems. Todd would be the one to take apart the fascicles, to make transcripts of lines in various correspondences, to sort most of what Todd later wrote “looked almost hopeless from a printer's point of view.”

30

Yet Todd's familiarity with Dickinson's manuscripts began after Dickinson's death; since Todd was Dickinson's brother's lover, Dickinson's sister-in-law and lifelong intimate, Susan Gilbert Dickinson, the recipient of most of the manuscripts Dickinson herself circulated, did not share most of her cache of manuscripts with Todd and Higginson. By late summer 1883, the affair between Austin Dickinson and Mabel Todd had been going on for about a year, long enough for it to have become a matter of social concern; when Todd was spending the summer of 1883 in New Hampshire, the letters between the two alternated between businesslike “cover” letters and passionate secret confessions that they asked one another to “destroy.”

31

One such enclosure of August 1883 from Austin to Mabel is a small scrap of paper:

Can you endure this silence longer?

I cannot

I said too much when I said you needn't write

'Tis too dreadful

Do speak

32

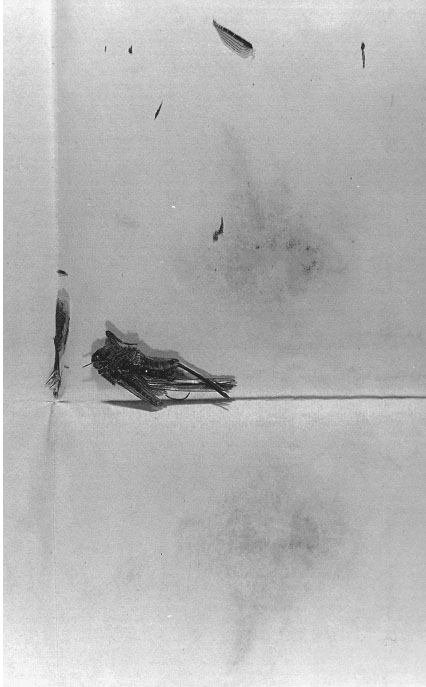

It was during this time of separation and tension between her brother and Mabel Todd that Emily Dickinson sent the lines that begin “Further in Summer / than the Birdsâ” to New Hampshire addressed formally to “Mrs. Prof. Todd,” signing them “Brother and Sister's Emily, with loveâ.” Enclosed within the lines was a small square of white paper, and enclosed in that square was a dead cricket, which has miraculously survived in the archive in disarticulated fragments (

fig. 17

). If the reference to “My Cricket” in the letter to Niles may have suggested that Dickinson had begun to reify her writing in view of a wider, less personal circuit of exchange, then her enclosure of the cricket in the intimate exchange of the lines addressed to more intimate correspondents suggests a very different view of their range of reference, or of the pathos they may have expressed for their reader.

Figure 16a. Emily Dickinson to Mabel Loomis Todd, 1883. Courtesy Amherst College Archives and Special Collections (ED mss, 66, 66a).

Figure 16b. Emily Dickinson to Mabel Loomis Todd, 1883. Courtesy Amherst College Archives and Special Collections (ED mss, 66, 66a).

This is to say that while the problem of lyric reference might seem to have been what was at stake in the preceding pages, the overlapping or incongruous details, seasons, public and private histories, battles and pets, sex scandals and insect remnants, books, newspapers, and all sorts of familiar letters that surrounded the lines later published as a Dickinson lyric could not be said to be what the lines are “about.” In fact, those contingencies may never have been the subject of the lines, but in any case they could only have formed part of what the lines

were

about; that is, the stories that could be unfolded from them may or may not have been relevant to the lines' potentially miscellaneous subjects (and objects) in the past. Once the lines were published and received as a lyric, those several and severally dated subjects and objects and their several stories faded from view, since the poem's referent would thereafter be understood as the subject herselfâsuspended, lyrically, in place and time.

That lyrical suspension may seem to be where Dickinson's lines on the cricket were always headed, detaching themselves over and over from whatever circumstances clung to them and readily attaching themselves to others. Yet, as we shall see, one of the most interesting aspects of twentieth-century critical thought about lyric subjectivity was the lack of such particular attachments; for literary theory in the United States in the twentieth century, the isolated lyric subject tended to become a social, even an historical and cultural, abstraction. In Dickinson's case, that meant that the densely woven fabric of social relations from which her verse was removed when it was edited and published as a series of isolated lyrics was replaced by a theoretical concept of “the social” as such; the lyric subject then became the personification of that concept. So, for example, when David Porter wrote in 1981 that what was by then Johnson's Poem 1068 “is a masterpiece in the art of the aftermath,” he did not mean the aftermath of Vanderbilt's accident, or of the Civil War, or of any particular summer, or of Higginson's wounds, or of Carlo's death, or of Dickinson's brother's love affair, or of the life and death of a cricket, but Dickinson's own “preoccupation with afterknowledge, with living in the aftermath.”

33

That preoccupation, in turn, typified for Porter “an extreme, perhaps terminal, American modernism of which [Dickinson] is the first practitioner” (1). Thus, in what was by then a tradition of lyric reading, the subject of the poem became an abstract person accessible to modern readers.

Figure 17. This cricket (now dismembered, though artfully rearticulated by the photographer) was enclosed with

fig. 16

in the small square of paper on which it is pictured, and on which it has left its mark. Courtesy of Amherst College Archives and Special Collections (ED. ms 66, enclosure).

As we have begun to see, such claims for Dickinson as representative have been made consistently for over a century, and some of them may even be true, but what concerns me here is what such statements suppose about the genre of Dickinson's work. For as Dickinson also became representative of the lyric, the lyric in turn came to represent a distinctly twentieth-century form of interpretation, and the aftermath of this interpretation removed lyric poetry from everything it may or may not have been about and made it about modern lyric readingâabout fictive rather than historical persons, and, inevitably, about the historical pathos attached to those fictions.

L

YRIC

A

LIENATION

In 1938, Yvor Winters published an essay entitled “Emily Dickinson and the Limits of Judgment.”

34

The essay bears an epigraph taken from the poem published in 1891 under the title “My Cricket”: