Divine Fury (30 page)

Authors: Darrin M. McMahon

Some, on the other hand, construed the individual genius’s capacity to incarnate and give voice to the whole in another, narrower way, and it was Herder who first articulated the conception most clearly. The genius, he insisted, could not be conceived apart from the people or nation in which he was rooted, for the genius was like a plant that grew in the soil of a particular culture and place. And given that individual poetic genius was, above all, a genius for language, it followed that the poet spoke not as a prophet for all places and times, but in the specific native tongue of his

Volk

. Shakespeare was the English genius par excellence precisely because he channeled the genius of the English people, capturing its cadences and rendering its idiom distinct. Homer did the same for the wild peoples of ancient Greece, while Ossian was the oracle of the ancient Scots, literally speaking for the people by committing their ballads to verse. In transcribing their genius, he assumed and became their voice.

31

Herder, it should be stressed, was a pluralist by temperament, little inclined to rank peoples on the strength of their own particular genius. Nor did he conceive of peoples in racial terms. His own understanding of genius was conceived largely in response to what he regarded as the universal pretensions of French civilization and art, which imposed, with uniform standards of taste and aesthetic laws, an artificial formality on sincere and unaffected expression. True genius was spontaneous, Herder believed, natural and wild, and indeed, civilization was most often its

enemy, killing off its vital source. The genius of the people would spend itself unless it was continually replenished and renewed.

But if Herder’s own historicist vision was tolerant, self-consciously celebrating difference, his insistence that genius was embedded in the soil in which it grew begged the question of how to properly nourish the seed. If the genius was a product of the people, and if genius was born, not made, then did it not follow that it was bred in bloodlines and nourished by race? Though Herder did not pose this question, later observers did, analyzing the genius and the genius of the people according to hereditary laws that seemed to mandate struggle, domination, and control. Would the individual genius summon the collective power of the genius of the people to dominate other nations, even as he dominated his own? The example of Napoleon, on this view, was as terrifying as it was inspiring, recalling the ancient truth that creation and destruction were one.

There was another concern as well, with a history similarly ancient. For if the power that found a place at the throne of the poet’s soul could turn him to despotism and oppression, it could also make him mad. “It is a great thing for a nation that it gets an articulate voice,” Thomas Carlyle would later claim in the context of poetic and prophetic genius. But the prophet who gestured to the promised land might lead his people astray, veering into the wilderness where they were prey to demons, ending not in deliverance but in bondage and sin. To a much greater degree than their predecessors in the eighteenth century, the Romantics contemplated those specters, and in so doing they gave new voice to a set of old associations, linking genius further to madness and alienation, anguish and anomie, transgression and crime. The voice of one crying out in the wilderness, in thrall to a force that possessed it, could be both frightening and tragic in its despair.

32

A

S EARLY AS

1819, the Romantic painter Eugène Delacroix was contemplating the fate of the Renaissance poet Torquato Tasso, who had been confined to an asylum against his will, mocked and abandoned in his madness, and tragically misunderstood. “What tears of rage and indignation he must have shed!” Delacroix wrote to a friend. “How his days must have dragged by, with the added pain of seeing them wasted in a lunatic’s cell! One weeps for him; one moves restlessly in one’s chair while reading his story; one’s eyes gleam threatening, one clenches one’s teeth.” Delacroix conceived a painting of the subject to provoke a similar response, and the final version of 1839 aims to do just that. Confined to a madhouse and pining for a love he cannot have,

Tasso sits alone in his cell. His gaze is at once distracted and intense, suggesting inner isolation and withdrawal, a man seeking refuge in his mind. Manuscript pages are strewn about the floor. The poet pulls at one, absentmindedly, with his foot. Three intruders gawk at him from beyond the bars of the cell; one of them points to loose pages on the couch. A gesture of mockery and derision, or the misplaced homage of a “fan”? In either case, persecution and torment are the apparent consequence, and Tasso, bathed in celestial light in an otherwise dark space, suffers like a saint, or even Christ. His luminescent limbs and exposed chest recall the holy passions of the figures of El Greco. Driven to madness, a man abused and profoundly misunderstood, Tasso is a martyr—a martyr to genius, who must bear the cross of his own imagination.

33

Such, at least, was the vision of Delacroix, the great French artist who has been described as the “Prince of Romanticism.” And insofar as his painting captures a uniquely Romantic vision, it was true to its times, if not to Tasso’s own. The poet himself, we can be sure, was never the perfect victim of Romantic legend. A pampered courtier whose brilliance was celebrated throughout his life, Tasso suffered all the same—from schizophrenia, some modern critics have speculated—and his spell in an asylum from 1579 to 1586 was no myth. Of his “genius” (

genio

) there can be little doubt—he was, in fact, among the very first men to use that term in the sense of a unique individual character or spirit, and he certainly possessed a genius of his own. The package proved hard for Romantics to resist. Hazlitt deemed Tasso’s life “one of the most interesting in the world.” Goethe wrote a play about him,

Torquato Tasso

, chronicling his persecution and creative struggles. Shelley wrestled with a tragedy of his own “on the subject of Tasso’s madness,” though he left behind only a few fragments. Byron, for his part, made a pilgrimage to the cell where Tasso was held and penned a lament in his honor, citing in the first of nine stanzas the

Long years of outrage, calumny, and wrong;

Imputed madness, prison’d solitude

,

And the mind’s canker in its savage mood

.

The poem, read in French translation, moved Delacroix deeply. The story of the poet’s plight had a similar effect on the woman of letters Madame de Staël, who viewed Tasso, “persecuted, crowned, and dying of grief while still young on the eve of triumph,” as a “superb example of all the splendors and of all the misfortunes of a great talent.”

34

Delacroix’s painting, accordingly, was a perfect rendering of a Romantic archetype, the suffering genius, maligned and misunderstood, haunted to the point of madness by his creative gifts. The archetype was not without its precedents. The connection to melancholy and madness, after all, was as old as Plato’s

furor poeticus

and the writings of Pseudo-Aristotle, and that connection had been reestablished and reinvigorated since the Renaissance. In the eighteenth century, too, an age well familiar with the classics, it was not uncommon to cite Democritus or Seneca, Horace or Longinus, on the mania that moved the poet, a practice that continued even after the language of the humors was abandoned in favor of new medical models that focused on the nerves as the source of mental instability. But if there was ever a touch of madness in the enthusiasm of genius, it was precisely the fear of an unrestrained enthusiasm—of the imagination run amok—that prompted Enlightenment authors to seek to contain it by means of judgment, reason, and taste. As the Scottish critic Alexander Gerard observed, making a point that was repeated time and again in the eighteenth century, natural genius “needs the assistance of taste to guide and moderate its exertions.”

35

The Romantics, it is true, did not do away with such talk entirely. But to a greater extent than their Enlightenment predecessors, they were comfortable with genius’s natural wildness and enthusiasm, ready to countenance—even to celebrate—the potentially dangerous sources of creative power. “This is the beginning of all poetry,” Friedrich Schlegel maintained, “to cancel the progression and laws of rationally thinking reason, to transplant us once again into the beautiful confusion of imagination and the primitive chaos of human nature. . . . The free-will of the poet submits to no law.” Schiller echoed the sentiment, observing in his

Letters on the Aesthetic Education of Man

that “we know [genius] to border very closely on savagery.” Genius was less a force to be contained than a power to be set free, and just as creativity and imagination could all too easily be suppressed by stultifying rules, the genius himself was forever threatened by those who lacked it. On this view, social convention, prevailing taste, and considered judgment were more apt to serve as shackles than as wise restraints. To be truly original, Romantic genius must liberate itself, laying down a law of its own, even at the risk of one’s sanity.

36

That, at any rate, was the pose. Very often it was nothing more. But even when such statements were merely rhetorical, they dramatized the creator’s potential for conflict, for struggle with others and with himself. Beyond the ramparts of the self stalked philistines of the sort who had imprisoned Tasso, uncreative and unimaginative minds, slaves to convention who were hostile to greatness and who taunted, gawked,

and persecuted deviation from the norm. These were the figures who gave weight to Christ’s words that a prophet was honored everywhere except in his own country and house. Many failed to recognize genius even in their midst. Was not Mozart buried in a pauper’s grave? Did not the English poet Thomas Chatterton die, neglected, in a garret? Tasso was hardly alone. “The history of great men is always a martyrology: when they are not sufferers from the great human race, they suffer for their own greatness,” the German critic Heinrich Heine declared. He was echoing a line of the French poet Lamartine: “Every genius is a martyr.”

37

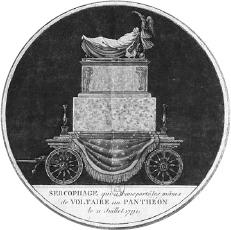

FIGURE D I.1.

Mirabeau arriving at the Elysian Fields, greeted by Benjamin Franklin, Rousseau, Voltaire, and a host of ancient and modern geniuses. Engraving after Jean Michel Moreau le Jeune, 1792.

Copyright © RMN–Grand Palais / Art Resource, New York

.

FIGURE D I.2.

“I-doll-ization.” A French representation of Benjamin Franklin from the eighteenth century, one of countless contemporary models, figurines, and images that responded to and fed the cult of genius.

Bridgeman-Giraudon / Art Resource, New York

.