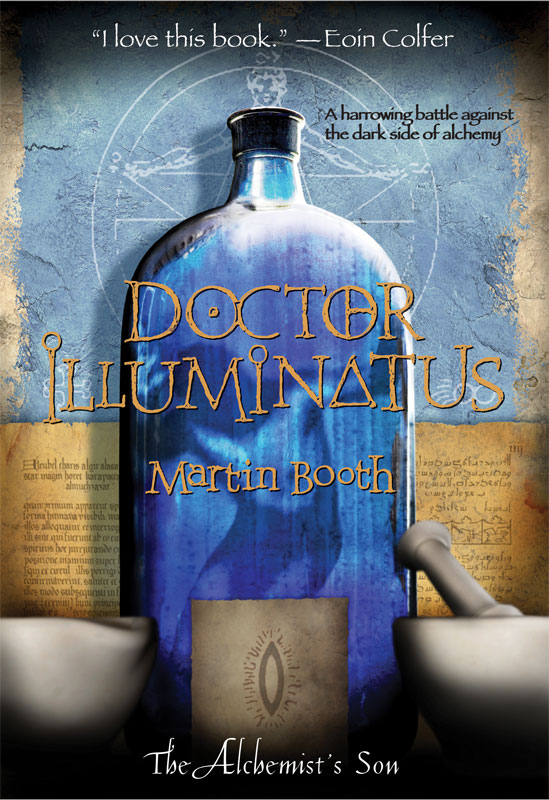

Doctor Illuminatus

Text copyright © 2003 by the Estate of Martin Booth

All rights reserved.

Little, Brown and Company

Time Warner Book Group

Hachette Book Group

237 Park Avenue, New York, NY 10017

Visit our Web site at

www.HachetteBookGroup.com

The “Warner Books” name and logo are trademarks of Hachette Book Group, Inc.

The characters and events portrayed in this book are fictitious. Any similarity to real persons, living or dead, is coincidental and not intended by the author.

ISBN: 978-0-316-02549-2

The text was set in Bembo, and the display type is Tagliente.

Contents

One: A Little Piece of History

Seven: The Dead and the Undead

For Lucy

The Alchemist’s Son

Martin Booth says: All the magic in

Dr. Illuminatus

is real: the chants, the herbs, the potions, and the equipment. The colophon [ ] used in this book is an ancient alchemical symbol representing rebirth. It is also known as the

] used in this book is an ancient alchemical symbol representing rebirth. It is also known as the

crux dissimulata

and was an early first-century Christian secret sign. The other [ ] is one of the many alchemical symbols for gold.

] is one of the many alchemical symbols for gold.

Alchemy, a curious blend of magic and science, was the chemistry of the Middle Ages. People who studied alchemy were called alchemists and they devoted their lives to the quest for the elixir of life and the means to turn ordinary metal, like iron, into gold. The third dream of alchemists was to create a homunculus — an artificial man made from dead material.

The Alchemist’s Son, set in contemporary England but inextricably linked to its ancient, bloody past, explores this dark side of alchemy.

A Little Piece of History

S

tuck to the heavy oak door was a fluorescent green Post-it Note upon which Pip’s mother had written

Daughter’s Room

with a broad blue felt-tip marker. Down the passageway, Pip could see other notes on other doors —

Son’s Room

,

Master Bedroom

,

Guest Room 1

and

Bathroom

. Each one stood out in the semi-darkness, she thought, like a glowing, square green eye.

Lifting the iron latch, Pip stepped into her new bedroom. Compared to her last, it was huge, at least four meters square, with ancient mullioned windows set in sandstone. Two of the walls were lined with dark oak panels, and the ceiling was held up by massive wooden beams as black as if they had been charred in a fire. The floorboards were each of different widths, according to where they had been cut from the trunk of the tree. As she walked to the windows, they creaked.

“Well, what do you think of it so far?”

Pip turned around. Her father was standing in the doorway.

“It’s . . .” Momentarily, she was lost for words.

“Is this a pretty spectacular house, or what?” her father said for her. “And this,” he looked around the empty room, “is a really stupendous bedroom.”

Pip grinned.

Spectacular

was one of her father’s favorite adjectives.

Stupendous

was the other.

“Your last one,” her father continued, “was a rabbit hutch by comparison.” He came to her side and gazed out of the window. “And to think that view’s hardly changed in the last five hundred years. There’s not a single tree out there that hasn’t got a preservation order on it. I can’t so much as prune a twig without local council permission.”

Following his gaze, Pip took in the neat garden with its trim flowerbeds, smooth lawn and an ancient mulberry tree in the center, the curve of the gravel drive, down the center of which grew a strip of grass, and the pasture beyond with massive oak, elm and beech trees dotted about it. Farther off still was a river lined with pollarded willows.

“Once, the house was moated,” her father went on. “See beyond the edge of the garden, where the ground dips? That was it. But in the eighteenth century, it was mostly filled in to make a ha-ha.”

Pip, who was never quite sure when her father was being serious, gave him one of her disparaging looks and sarcastically replied, “Ha! Ha!”

“Really,” he said, briefly pretending to be hurt. “It was a landscaping feature. A ha-ha is a grassy ditch, surrounding a house, that slopes down gently towards the building, but has a stone wall on the house side. The idea was to keep animals out of the gardens without a fence or hedge spoiling the view.” He turned from the window and walked over to the door. “Your mother’s put the kettle on. Tea and cake in ten minutes.”

After he had gone, Pip unfolded the estate agent’s leaflet she had in her pocket and, not for the first time that day, read the blurb printed on the front page beneath a color photo of the front elevation of the house.

Rawne Barton

, she read,

situated in beautiful countryside three miles from the pretty market town of Brampton, offers a rare opportunity to purchase a Grade I-listed, landed-gentleman’s country house set in thirty-two acres of pasture, formerly a deer park. Originally built in 1422, but extended over the following hundred years, the property comprises a spacious and superbly appointed six-bedroom family house with extensive period features including contemporary linen-fold paneling, beamed ceilings with carved features and magnificent fireplaces. Recent extensive modernization has been conducted to the highest standards and in complete keeping with the architectural and historical aspects of the house. A range of contemporary outbuildings includes a stable (restored and providing ample space for vehicles), a coach house and a malt-house (both in need of renovation: with planning permission)

.

The photograph showed a building made partly of white wattle-and-daub and partly of brick with black timber beams built into the walls. Above the tiled roof stood two stacks of chimneys, added in the sixteenth century, made of the same sandstone as the window frames, but twisted in spirals like sticks of old-fashioned barley sugar.

“Do you know what

barton

means?”

Pip looked around to see her twin brother, Tim. The knees of his jeans were grimy, his T-shirt was smudged with dirt and his brown hair looked as if it had been lightly powdered with flour.

“Try knocking,” she said sharply.

“Door’s already open,” Tim responded, “and I’m not coming in.” He slid to the floor, leaning against the doorpost. “It means a cow shed,” he went on.

“No, it doesn’t,” Pip corrected him. “It means a farm owned by a landowner, not given to tenants. I looked it up.” She ran her eye up and down her brother. “Why are you so grubby?”

Tim ignored her question.

“And you know what

Grade I-listed

means, don’t you?” he continued. “It means we can’t put up a satellite dish. Goodbye MTV and the Cartoon Channel.”

“We can have one of those square ones in the attic,” Pip said. “Grade I only means you can’t alter the appearance of the house or destroy any historical features.”

“They don’t get such a good signal,” Tim rejoined. “Besides, I’ve seen the attic. No chance. The rest of the house might have been modernized, but that hasn’t. The cobwebs are like table-tennis nets.”

“You’ve been up there?”

“There’s a door at the end of the passage,” Tim said. “I thought it was an airing cupboard, because it’s got shelves and a copper water cylinder in it, but at the back there’s an old paneled wall. One panel has a handle and slides sideways. It’s a bit of a squeeze, which is probably why the builders didn’t bother to go up there. Behind that, there’re steps. The attic floor’s boarded, but there aren’t any rooms or anything, just a big space with a little window at the end and a lot of beams, crud and cobwebs. And a dried-up dead bat.”

One of the removal men appeared at the door carrying a large cardboard box with yet another Post-it Note taped to it.

“You the daughter?” he asked. “This your room?” He didn’t wait for an answer but, checking the Post-it Note on the door against that on the box, entered, stepping over Tim and looking around. “Nice. Very nice. Quite a place your mum and dad’ve bought.” He put the box down and glanced out of the window. “You know what you got here, don’t you? You got a real little piece of history, you have.”

The garden was protected on two sides by stone walls about two meters high, with rambling roses and honeysuckle trained up them. The flowerbeds were thick with bushes and low shrubs, most of which were perennials. Some had thick trunks and were plainly very old, having been carefully pruned over the years. Quite a number were in bloom and one, a jasmine with tiny white flowers like thin stars, was giving off a heavenly scent. The grass of the lawn was ankle deep and even now, in the early afternoon, damp.

Pip walked across the grass to the mulberry tree. It was positively ancient, leaning slightly to one side as if it were tired of supporting itself against the winds of time. Under the trunk was wedged a tough oak bar to hold it up. Like a mottled green umbrella, the tree spread its branches out from gnarled and twisting boughs; the bark was hard, scaly and old. They reminded her of her grandfather’s arthritic fingers.

Leaving its cool shade, Pip went over to the edge of the ha-ha. It was just as her father had described it. The ditch was filled with grass in which tall ox-eye daisies and buttercups were growing. At one end, where the soil looked to be damp up against the loose stone wall retaining the garden, grew a clump of mugwort.

Pip knew her plants. She had once toyed with the idea of going to horticultural college and becoming a famous gardener, laying out the properties of film stars, royalty and millionaires. Perhaps, she had dreamed, she might end up as the head gardener for a palace or grand stately home. She had never in her wildest imagination thought that she might one day live in a smaller equivalent of such a house.

Making her way back towards the heavy oak door that led from the garden to the hall, Pip suddenly noticed a strange bush. She had never seen anything like it before. About two meters high and hidden against the wall behind other shrubs, it had large, dark leaves that looked as if they were made of velvet. Yet it was not the leaves that caught her attention, but the flowers. They were about fifteen centimeters long and hung down under their own weight. The color of old ivory, they were trumpet-shaped with frilled petals. The bush held only three flowers, although the remains of several more lay rotting on the ground beneath it. Five or six buds were waiting to open.

Bending to a flower, Pip gently lifted it up. It was surprisingly heavy. Clearly, few insects had visited it, for the stamens were still covered in a green-tinged pollen. She sniffed at it to see if it had a perfume. Instantly she felt giddy and, letting the flower go, reeled several steps back, her head spinning. The sensation passed quickly, but it left her puzzled. Surely, she thought, the flower could not have had that effect upon her. Somewhat more cautiously, she sniffed the flower again. It had a strange scent, a sort of mixture of sour milk and apple juice. No sooner had it hit her nostrils than, once more, she felt dizzy.